A modern design of Charlap Family Flag (Design © Gil Dekel)

By Arthur F. Menton

and Dr. Gil Dekel for additional notes {in brackets}, corrections, and images.

Chapter XXVI – Four Centuries in Iberia

The four centuries that our ancestors spent in Spain roughly coincide with what has been called the Golden Age. It was the age of Solomon Ibn Gabirol, Yehuda Halevi, and Maimonides. That era came to an end in 1492 with the expulsion of the Jews from Spain. On the 500th anniversary of that event the Jewish Museum in New York City held a retrospective on Jewish life in Moslem and Christian Spain.

The picture that emerges is nuanced, shaded. There is no longer a pure Golden Age, but a convivencia [coexistence] that is not total harmony. Medieval Spain was a pluralistic society in which the separate communities engaged in business with each other and influenced each other with their ideas and cultural forms. At the same time, these groups mistrusted each other and were often at war with one another. Culture flourished despite politics, but flourish it did and left such a rich legacy that for centuries after men and women thought it had been created in an age that was “Golden” in every sense of the term. [1]

The intermingling of the three civilizations provided the fertile substratum for the flowering of Jewish culture but the Jewish religious heritage was invigorated by the influx of emigres from Babylonia, who brought with them Talmudic learning, philosophic and scientific speculation, and a rich poetic tradition. Among these exiles from the East were the sons of Chiskiah, the martyred Rosh Hagolah. It was their descendants who gave rise to some of the great families of Iberia, including the Abravanels and Ibn Yahyas.

Chiya al-Daudi was the distinguished progenitor of the Ibn Yahya family of Portugal and Spain. Born between 1080 and 1090 C.E., he became a prominent rabbi, composer, poet, and advisor to the King of Portugal. His hymns are still used in Sephardic congregations throughout the world. Chiya died in Castile in 1154. His son Yaish, known as Ibn Yahya, was born circa 1120 and achieved fame as a great scholar and politician. He died in 1196. As a result of their services to the throne, King Alfonso I awarded Yaish and his son Yahya el Negro vast estates formerly belonging to Moors. The Jewish Encyclopedia mistakenly gives 1150 as the approximate date of death of Yahya Ibn Yaish. This is clearly impossible. It is more likely that 1150 was his date of birth. In a chart on the Yahya pedigree, the same encyclopedia lists his name with the date 1055 C.E. but does not indicate whether that refers to his birth or death. Confirmed dates of Yahya Ibn Yaish’s father and grandfather, as well as his descendants, corroborate family documents which list his date of death as 1222. [2]

At about the time that Yaish and Yahya were acquiring former Arab lands in Portugal, a similar process was occurring in Spain.

In October 1149, the Count of Barcelona, assisted by other knights, conquered Lerida. . . Jews were employed in its fiscal administration. In the years immediately following the conquest of Lerida, we find the commander of the Order [Knights Templar] permanently leasing to Jews some of the lands recently appropriated from Arabs. A Jew, by the name of Yahya ben David of Monzon, helped organize the administration of the district. He is the first Jew to be designated in official documents as “bailiff’. Yahya served primarily Alfonso II (1162-1196) of Aragon. His signature, in Latin characters, appears on documents dealing with taxes and other fiscal matters, on writs of exemption from taxes, on the charters of newly established Christian villages; and we find him, too, approving leases and transfers of land. He signed an official document fixing the boundaries of the city of Lerida under Moslem rule. In all, he appears to have fulfilled an important function in the apportionment of the conquered territory. He was himself the beneficiary of extensive grants of land in the vicinity of Lerida, with permission to rent them to whomever he desired, Christian, Jew, or Saracen. He also owned wine cellars in the Jewish citadel of Lerida. [3]

Lerida and Monzon are close to Saragossa. We know that one of Chiskiah’s sons sought sanctuary in Saragossa after the murder of Joseph HaNaggid. It is likely that Yahya of Monzon descended from this Aragon branch of the family. Also in Aragon, southwest of Saragossa in the city of Calatayud was a magnificent edifice known as the Ibn Yahya synagogue, after its builder Aharon Ibn Yahya, “besides two other chapels of prayer and study that bore the names of their founders.” [4]

During this period, Aragon continued to be a mixed blessing for the Jewish community and the Ibn Yahya family. Aragon’s leader, Pedro III, insured increased population by providing safe passage to Jews escaping from Tripoli in 1278. Yet, a year later Pedro enforced a papal bull which insisted on energetic measures to convert Jews to Christianity. These policies gave rise to anti-Jewish riots throughout Aragon. The following year saw an improvement as Catalonian noblemen revolted against Pedro. They found sympathy among Jews who were rewarded with positions in the Catalonian administration. Jews were responsible for taxes and finance, arms supply, and judiciary appointments. Yahya family members filled many of these functions. In 1284 Pedro III reverted to helping Jews who were accused of harboring converts to Christianity. His forbidding of a Dominican inquisition was not through altruism. He wished to insure the continuance of the Jewish community as a source for revenue to his realm. Pedro died in 1285 and the new King of Aragon issued a proclamation guaranteeing his protection to Jews who settled there. [5]

Next in our main line after Yahya Ibn Yaish was Yehuda, listed as Prince Don Yehuda in Shalshelet ha-Kabbalah. Yehuda had two sons, Yahya and Yosef. Little is known of Yahya but Yosef attained great wealth and built an imposingly elegant synagogue in Lisbon at his own expense. He was also the author of a Talmudic commentary which is no longer extant. Yosef was known as ha-Zaken which can mean the Elder, the Senior, the Learned, or the Bearded. If Zaken referred to old age, it did not rub off on Yosef’s son Shlomo who died prior to 1300. Also known as ha-Zaken, despite his brief life, Shlomo was a philosopher and royal military advisor. He was concerned about the extravagant life style of the community and tried to convince his fellow Jews to curtail their ostentatious display of wealth. He saw the love of luxury as eating away at the soul of the people and was fearful that it could arouse the wrath of the gentile population.

Shlomo’s two known sons were Gedaliah ha-Zaken and Yosef ha-Meshorer. Meshorer can mean the Happy, the Tenth, or could possibly refer to an Official. Little more is known of Yosef other than he had a son Shlomo Ibn Yahya. Gedaliah was the more notable of the brothers. He served as physician to King Ferdinand until he lost the favor of the court in 1370. He was invited by Henry of Castile to administer the Jewish communities under his sway. Gedaliah received a yearly stipend of 5,000 gold ducats which was probably obtained by taxing the Jewish population. Gedaliah settled in Toledo where he died at a very old age, truly ha-Zaken.

The line continues through Gedaliah’s son David Ibn Yahya Negro, known as the Rab shel Sepharad. The family was now well-established in Castile. In the war between Portugal and Castile, David provided immense help for which he incurred the wrath of King Joao of Portugal. Joao confiscated many of the Ibn Yahya estates in Portugal for what he saw as the treasonous behavior of David. On the other hand, David was appointed Chief Rabbi of Castile and King Ferdinand awarded him the title of Almoxarife, which he held until his death in Toledo in October 1385. He was buried with honor and his tombstone has been preserved.

We know of four sons of David Ibn Yahya Negro ben Gedaliah and six grandsons. Their lives were profoundly influenced by the anti-semitic storms which were starting to rage throughout Christian Spain. In 1378, Archdeacon Ferrant Martinez embarked on a vitriolic campaign of hatred directed against the Jews of Seville. He proposed that Jews be restricted to their own quarter to prevent their having an insidious influence over Christians and he espoused the destruction of the twenty-three architectural gems which served as synagogues. Upon becoming administrator of the diocese in 1390, Martinez challenged the secular authorities by unilaterally summoning Jewish tax farmers to an ecclesiastical court and by forcibly converting Jewish-owned slaves to Christianity. The weak crown was no match for this demagogue who could whip up popular fervor with his vulgar harangues and religious fanaticism. With the death of King John I of Castile, disorder spread throughout the kingdom. It was not long before the violence had spilled over into Aragon. The year 1391 was one of devastation in most of Spain.

The storm that broke in Seville passed over all the other communities of Andalusia, and extended to New and Old Castile. The disorders took varied forms, but the outcome was always the same . . . In Toledo on June 20 R’ Judah, a grandson of R’ Asher ben Yehiel, his family and students died the death of martyrs; many prominent members of the community suffered the same fate. However, there were many conversos. The famous synagogues of Toledo fell into Christian hands, and some were destroyed. Moslems also participated in the riots. In Madrid most of the Jews were killed or baptized. The municipal authorities cast all the blame upon the “little people” (pueblo menudo), who continued to loot in the vicinity for a whole year. . . [In Toledo], Seville, and Cordova Jews had been killed, despoiled and forced to change their religion because the Archdeacon of Ecija [Martinez] had incited the “little people”, who lacked understanding, were not concerned for the harm done to the king’s interests, did not respect the king’s justice, and had no fear of G-d in their hearts. [6]

The four sons of David Ibn Yahya, ha-Rab shel Sepharad, Gedaliah, Yitzhak, Yehuda, and Shlomo were all born in Toledo in the late fourteenth century. Little is known of the fate of Gedaliah and Yitzhak, other than that Gedaliah had three Jewish sons. In 1391, the year of the great terror, Shlomo and Yehuda fled to Portugal. Apparently, King Joao did not visit the sins of the father upon the sons, for Yehuda found great favor in his court. Queen Philippa was especially taken with Yehuda and through her his influence extended to the king. One story that has been handed down tells of Yehuda’s thwarting of a plot to bring the terror of Spain to Portugal. One Vicente Ferrer had requested permission of the king to instigate a propaganda campaign against the Jews of the realm. Yehuda and his brother advised against such a policy and King Joao informed Ferrer that he could commence his campaign if he wore a red-hot crown atop his head. Yehuda was a noted author of responsa and piyuttim. He was, perhaps, the most honored Jewish poet of his time in Portugal. His most moving poems are elegies concerning the fate of his co-religionists in Spain. Like his father, Yehuda was known as Negro but he also was known as ha-Meshorer. He died in 1420 at the age of fifty-five. Yehuda’s descendants appeared in Italy where they were prominent rabbis and communal leaders. Yehuda’s brother Shlomo lived ten years longer and it is through him that the lineage progresses.

Shlomo’s son, Gedaliah, was born in Lisbon in 1400. He lived only forty years but achieved prominence as a philosopher and astrologer. His title was Mestre Guedelha Fysico e Astrologo and about 1428 was appointed court astrologer to King Joao I. Joao died in 1433 and his son Duarte acceded to the throne. Duarte, unlike his father, instituted oppressive measures against the Jews. Gedaliah had been aware of Duarte’s inclination and had prophesied a brief, disastrous reign. Gedaliah’s prophecy proved accurate as Duarte became gravely ill. In retaliation for what was considered Gedaliah’s curse, restrictions on Jews became more stringent. We do not know very much of Gedaliah’s personal life.

Gedaliah’s brother Yosef was an accomplished poet, a man of extraordinary handsome features and of superb physical stature. When King Duarte imposed his oppressive measures against the Jewish community, Yosef, with his brother Gedaliah, left Portugal for Castile. Yosef continued to compose liturgical poetry and led a comfortable life. He underwrote the extensive repair of the splendid Ibn Yahya synagogue of Calatayud, built by his ancestor Aharon.

David, the third son of Shlomo, who died circa 1450, had four known sons of his own: Yehuda, Shlomo, Gedaliah, and Yosef. Yehuda’s progeny became Kabbalists and migrated to Eretz Yisraelwhere they settled in Safed. Shlomo was a true son of the Renaissance, a scholar who was revered by the royal court. King Alfonso V honored him repeatedly before he died in 1490. Even in death Shlomo was given royal honors and his grave has been preserved to this day. Shlomo was the father of at least three sons. One of them was the renowned David Ibn Yahya, named for his grandfather. The date of David’s birth is in dispute. Some sources give it as 1440, others 1455. Nevertheless, while still a young man he was appointed Chief Rabbi of Lisbon. He held that position during the period of Catholic paranoia concerning Jews who had been converted after the terror of 1391. That period was characterized by a phenomenon which was unique in the history of the Jews.

For the first and only time their morale broke. Very large numbers of persons, seeing no hope for the future, and their convictions undermined by the syncretizing tendencies characteristic of the Hispano-Jewish intelligentsia, saved their lives by submitting to baptism. Their number was reinforced by a constant profession of fresh neophytes who went over to Catholicism under a more or less distant threat of violence, or out of sheer despair, in the following years. . . they were suspected – and in many cases with reason – of scant interest in their new religion, and a secret loyalty to the old one. Hence the religious prejudice that had formerly been so widespread against the Jews was turned into what would today be termed “racial” channels, and was shared by their converted kinfolk, known as conversos, or New Christians; or else by an old term of opprobrium, originally signifying swine, Marranos. This problem – a very real one from the point of view of the Catholic church – was henceforth paramount in Spain, and inevitably hastened the final disaster which was not far distant. [7]

The same Vicente Ferrer, who had failed in pushing his anti-Jewish program in Portugal, achieved more success in Spain. His Dominican order led the way in whipping up popular frenzy against the Jews. Those who had tried to avoid persecution through conversion did not escape the hatred. The growing importance of the conversos in the Spanish economy engendered intense envy and attempts were made to expose them as secretly practicing Jews. In 1476, the year David Ibn Yahya ben Shlomo assumed his rabbinic post in Lisbon, the Catholic paranoia had spread to Portugal. David was accused of encouraging “Marranos to relapse into Judaism.” For this “crime”, of which he was most probably guilty, he was sentenced by King Joao II to be publicly executed in an auto-da-fe. He escaped with his family to Naples only to be captured once again. He was able to purchase his freedom with money raised through the sale of his extensive library. He then fled to Corfu and ultimately found his way to the Ottoman Empire. Through all his wanderings he found time to write many biblical commentaries, works on Jewish law, and his masterful grammatical treatise Leshon Limmudim. Another major work was Shekel ha-Kodesh. Both of these titles were written for his first cousin with whom he shared a common name and whom he tutored. When he died near Constantinople circa 1528, David was recognized as one of the most distinguished rabbis to have originated in Portugal. Despite his poverty and sufferings he gave rise to a large family. His son Yaacov Tam was rabbi in Salonika and was also a court physician in Constantinople. Yaacov Tam was born in Portugal in 1475 and spent his youth fleeing persecution. He became a noted Talmudist and was the author of many commentaries and responsa. He died in 1542 leaving three sons: Gedaliah, Abraham, and Yosef.

Yosef ha-Rofe (the physician) tended the medical needs of Suleiman the Magnificent. He was in constant attendance with the Sultan, in war and in peace, and finally fell in battle in 1573. Yosef ha-Rofe was keenly aware of his distinguished ancestry and underwrote the publishing of many works by noted Ibn Yahya rabbis. His brother Gedaliah was also a physician, scholar, and teacher. He served as rabbi in Salonika and Adrianople until the middle of the sixteenth century. His last years were spent in Constantinople where he was a prolific writer on Hebrew literature. He died in 1575. Gedaliah’s son, Yaacov Tam, continued his father’s devotion to Hebrew literature. His huge inheritance allowed him to pursue this passion free from outside pressures. After Gedaliah’s death, Yaacov Tam moved to Salonika where he befriended such well-known poets as Saadia Lougo and Abraham Reuben. Yaacov Tam’s most influential work was a compilation of writings by his forefathers along with commentary. It was published posthumously in Venice in 1596 under the title She’elot u-Teshubot Ohole Shem.

Yaacov Tam Ibn Yahya ben Gedaliah had a prominent cousin named Moshe. He was the son of Yosef ha-Rofe and like his father was a physician in Constantinople. In the latter half of the sixteenth century a plague afflicted Anatolia. Moshe used much of his fortune in establishing centers for treatment of the victims. His generosity was exceeded only by his unselfish care which he extended to all in disregard of his own safety. He was beloved throughout Turkey. Moshe’s son Gedaliah reverted to the literary passion of the Ibn Yahya family. He lived in Salonika where he gathered a large number of writers and poets with the aim of promoting Hebrew literature and poetry.

We return now to the family of David Ibn Yahya ben Shlomo who died in 1450. We have discussed two of his sons. A third was Gedaliah who was born in Lisbon in 1437. Leaving the troubles of Iberia, he settled in Constantinople where he became a respected philosopher. He advocated healing the schism between main-stream Judaism and the Karaites. His major published work was Shibah Enayim, in which he discussed the seven cardinal virtues of the Jews. Gedaliah died in Constantinople in October of 1487.

The fourth son of David was Yosef, born in 1425. It is Yosef who is the direct link in the Ser-Charlap genealogy. His life typifies the wild swings of fortune which befell the Jewish community of that era. He had been a confidante of King Alfonso V who gave him the appellation “the Wise Jew.” Portugal was being flooded with refugees from Spain and there was some hostility between the two Jewish communities. Yosef was instrumental in assuaging this conflict. Yosef was sixty-seven when the Jews were expelled from Spain in 1492. At first they were welcomed by King Joao, but later Catholic pressure for conversion became extreme. In 1495, Joao decided to make Yosef an example and have him publicly renounce Judaism and accept Jesus as his savior. The reasoning went that most Jews would follow the pattern set by the honored patriarch of the Ibn Yahya family. Yosef would have none of it. He fled Portugal by ship with his three sons and a considerable sum of money. He sailed into the Mediterranean but misfortune forced him to land in a Castile-controlled port, where he was seized. Ferdinand and Isabella had already stated that Spain was to be free of Jews. Yosef was sentenced to be burned at the stake. Through the intervention of the Portuguese Duke Alvarez of Braganca, the family was permitted to continue their journey. Five months later Yosef appeared in Pisa, Italy where he was imprisoned by Charles VIII, a Frenchman who was threatening the city-state. A huge bribe bought his freedom and he then sought the protection of the Duke of Ferrara. For a while Yosef and his family lived in peace. Soon enough he was charged with tutoring Marranos in Jewish practices and was once again imprisoned. The elderly Yosef was subjected to excruciating torture until another bribe secured his release. However, in 1498 he died from the effects of his imprisonment. He was thenceforth known as Yosef the Martyr.

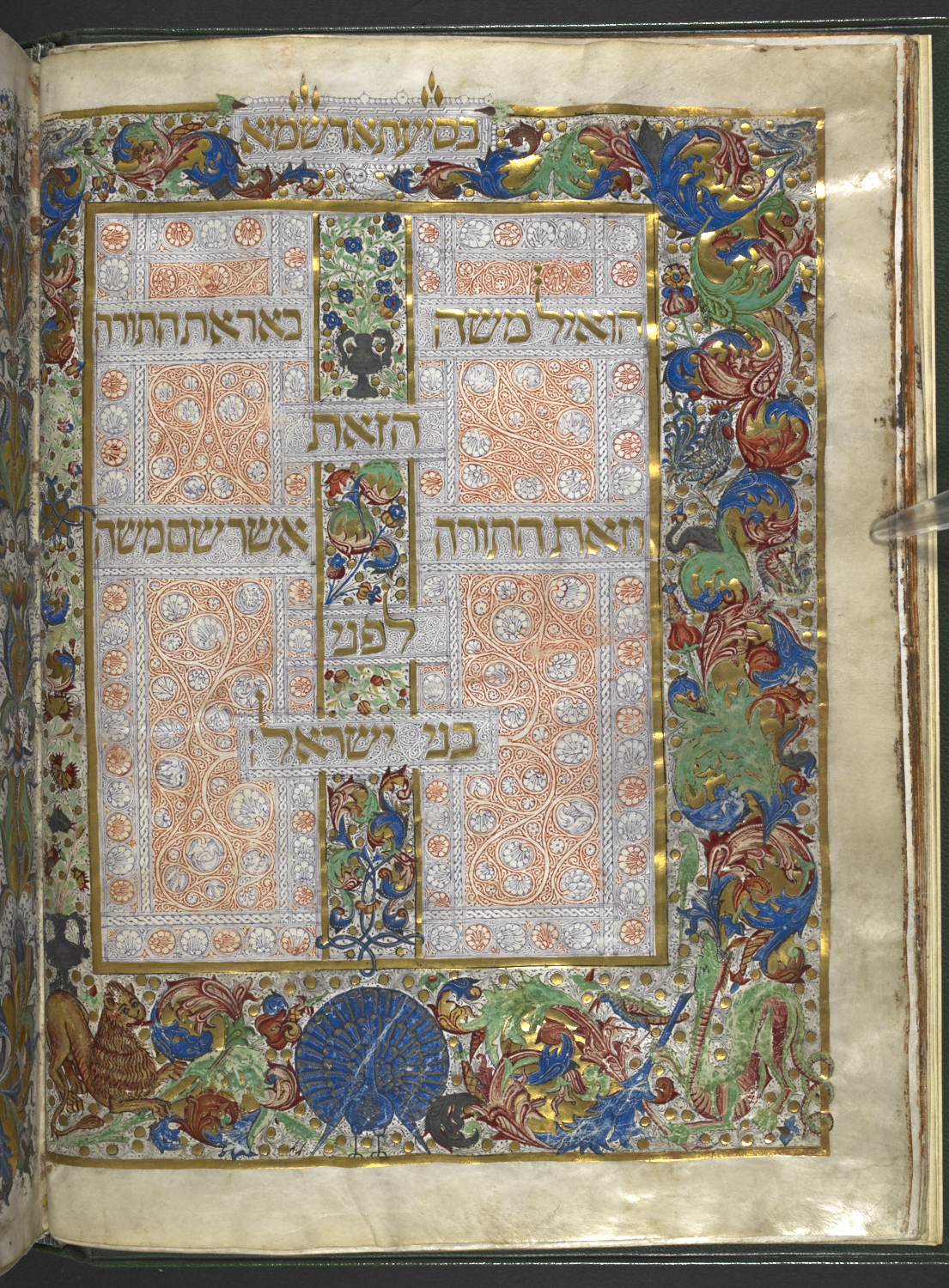

The life of Yosef conjures up thoughts of Hebrew illuminated manuscripts. If the reader will bear with me it will become clear why this is so. The earliest manifestations of Hebrew manuscript illustration occurred in the Middle East and the practice spread throughout the Islamic conquests and eventually into Spain and Portugal. During the Middle Ages in Europe, this became the most prominent art form among Jews. The scribes and artists who worked on these holy books were accorded great honor by the Jewish communities. As early as 1262, Abraham Ibn Hayyim wrote a book in Portuguese and Hebrew concerning the illuminated manuscript. David Goldstein of the British Library observes that “particular love and care were lavished on the copying of manuscripts of the Bible, the most sacred possession of the Jewish people.” [8]

The five megillot (Song of Songs, Ruth, Lamentations, Kohelet, and Esther) were often intricately decorated with art forms. The machzor, or festival prayer book, was another frequently illuminated manuscript. Most Jewish festivals are associated with historic events which lend themselves to creative expression. Perhaps the Passover Haggadah is the “most extensively and richly decorated” {David Goldstein, 1985, p. 38} of all the Jewish prayer books. Many unique examples survive and have been reproduced in facsimile editions. Marriage contracts, ketubot, were a favorite of medieval Jewish artists and scribes. The illuminated ketubah has continued to be valued throughout the Jewish world and its popularity among many newly married couples has stimulated a renaissance of this form. Illumination was also employed by Jewish artists in embellishing works of science, philosophy, medicine, and Jewish law. An excellent example of the latter is the Mishna Torah written by Maimonides in Egypt in 1182. In 1991, we discovered {a copy of} this magnificent volume while doing research in the British Library. Goldstein points out that “the introduction and each of the 14 books in which the work is arranged are elaborately decorated with foliage and flowers and delicate filigree work.” [9] The volume we saw was copied from the original {1182} Rambam {Maimonides} work. {It was copied} in Lisbon from September 1471 to August 1472. To our amazement, we noted that the artist was Solomon Ibn Alzuk who completed the manuscript for Yosef Ibn Yahya ben David! This is our Yosef the Martyr.

{In the second volume of this book (at the British Library, Harley 5699, Colophon, folio number 434v) Yosef is mentioned as the patron of the book: Yosef ben David ben Shelomoh ben Rabi David ben Gedalyah the elder.

Goldstein repeats this information (in his book, page 58). He states that Solomon Ibn Alzuk copied the volume for Yosef Ibn Yahya (Joseph ben David Ibn Yahya) in Lisbon.}

Excerpts from Maimonides’ Code of Law, embellished with sumptuous full-border illuminations. Mishneh Torah, Lisbon, 1472 CE. Dimensions: 1105 × 1500. Location: British Library (Harley MS 5698). Book commissioned by Yosef Ibn Yahya ben David. Artist: Solomon Ibn Alzuk. Image provided by the British Library, in a press releases kit, November, 2017, as well as in their Asian and African studies blog, 17 July 2020. Image in public domain.

The discovery of our ancestral Mishna Torah stirred up some ambivalent thoughts. How did this volume get from the Ibn Yahyas to the British Library? Was it seized by the Spanish or Portuguese oppressors and later captured by the British? Or did it take some more tortuous path to its present berth? A few years ago, there was a traveling exhibition of sacred Hebrew manuscripts held by the Vatican which, after a year-long tour of the United States, was shown at the New York Public Library on 42nd Street. At that time an advertisement placed in many national papers raised some cogent points.

It is well known that the Church, for centuries, as part of her deliberate plan to eradicate Judaism, engaged in a systematic campaign to seize Hebrew books and destroy Jewish libraries. Firstly, to create and maintain the absurd notion that Judaism, after the death of Jesus, was a sterile and unproductive religion. Secondly, to deprive Jews of their means of education and thereby to throttle the unusually high level of Jewish scholarship. Thirdly, to search in Jewish writings for some glib arguments which could be turned against Judaism and force conversions to Christianity. They were used to fabricate ammunition against Judaism in rigged disputations which rabbis were forced to attend. Lastly, while most of the Hebrew manuscripts thus wrested by force from the persecuted Jewish communities were burned, or hidden in churches or monasteries, some were torn apart to be sold as book binding material. Pope Urban II unleashed blood-thirsty mobs for the First Crusade in 1096 who promptly slaughtered thousands of outstanding Jewish scholars in communities along the Rhine River and destroyed their libraries. In 1244, under Innocent IV, twenty-four cart loads of Hebrew manuscripts, mainly copies of the Talmud, were burned in public in Paris. Pope Paul IV, before he died in 1559, destroyed every Hebrew book owned by the Jews of Rome. His successor, Pius V, punished any Jew caught still owning a single book. This on-going cultural genocide was so thorough that only one hand written copy of the Talmud survived the Popes’ crusade against Jewish writings – the famous Munich Talmud manuscript. Can anyone imagine that Jews, thus constantly fighting to preserve their sacred books, would sell or donate them . . . to the Vatican, as the promoters of the exhibition would have us believe? NO! Every manuscript in the Vatican has its blood drenched roots in pogroms and massacres of Jewish communities throughout the centuries. In view of the tragic trail of suffering and persecution which these precious books represent in Jewish history, it must be considered highly inappropriate to use them as a kind of traveling circus for the financial gain of the Vatican. The whole enterprise betrays gross insensitivity to Jewish suffering and pride. The exquisite manuscripts, painstakingly penned by skilled Jewish scribes and artists, were produced generation after generation to be used for religious devotion and Jewish scholarship. The mint condition of most of them proves that they were snatched from their owners before their purpose could be fulfilled for any length of time. [10]

Viewing these works and recognizing the dedication of those who produced them, conjured up similar thoughts to those expressed by the Committee For the Recovery of Jewish Manuscripts. Upon seeing the Maimonides Mishna Torah in the British Library, crafted for our relative Yosef Ibn Yahya, these sentiments were rekindled. It is time for Christian institutions to atone for their murderous actions against our people. A small beginning would be the return of sacred Hebrew manuscripts to their rightful owners. It might be too much for our family to lay claim to the Ibn Yahya volume, but this and especially the treasures sequestered in the Vatican should be “housed in the National Library in Jerusalem, again the center of Jewish scholarship, in the midst of the Jewish capital, again a thriving center of Jewish religious devotion and practice.” [11]

Yosef’s three sons were David, Shlomo, and Meir. Shlomo was repelled by the treatment of his father and left Italy, finally settling on Rhodes. That island had been captured by the Turks in 1523 and the Sultan immediately issued an order to settle Jews there for economic reasons. Shlomo’s brother Meir stayed in Italy, settling in Oulina where he pursued a life of literature and poetry. His major surviving accomplishment is a poetic introduction to Yehuda Halevi’s Ha-Kuzari.

David Ibn Yahya ben Yosef was born in Lisbon in 1465. He was thirty-one when he fled Portugal with his father and brothers. In Portugal, he had married Dinah who proved to be a heroic figure. Disguised as a man, she joined her husband and his family in their flight from Lisbon. During the escape she refused all food but bread and water. Once in Pisa she avoided French troops by hiding in the famous tower. Legend has it that to avoid capture she leaped to the ground without suffering injury. She then fled to Florence. Later, reunited with her husband, they went to Naples. David had studied under the direction of his first cousin David Ibn Yahya ben Shlomo and was appointed Rabbi of Naples in 1518. He served in that post for twenty-two years until that kingdom followed the policies of so many other “enlightened” Catholic nations and expelled the Jews. Six years earlier David had averted an earlier expulsion edict. He was an ardent fighter for Jewish rights everywhere and believed in the unity of the Jewish people. That belief led him to solicit funds in diverse Jewish communities to help their brethren in need. For example, in 1533 a group of Jewish prisoners from Tunis arrived in Naples. Their freedom was up for sale but the local community had exhausted their funds. David sent emissaries to distant Italian communities and even into France to appeal for contributions to the ransom. The campaign was successful and the Tunisian Jews were released.

David was also a teacher and an author of several grammatical and philosophic books. More importantly from our perspective, he wrote an autobiographical account giving information about his antecedents. These works were preserved by his grandson Gedaliah. After the expulsion from Naples David wandered through Italy and finally died in 1542 at Imola. He was eulogized by Rabbi Meir Katzenellbogen of Padua, the most respected Italian Jewish leader of his time. David had willed that he be buried in Eretz Yisrael. His body was sent to Safed where it was given a ritual burial supervised by Rabbi Joseph Caro.

Dinah had given birth to her son Yosef shortly after her arrival in Florence in 1494. Yosef was a scholar and author chiefly remembered for his theological treatise Torah Or. Yosef’s wife, Abigail, bore four sons: David, Ahikam, Gedaliah, and Yehuda. Yosef also had a nephew Shlomo, a Portuguese exile who settled in Ancona, one of the Papal States on the Adriatic, just east of Perugia. Shlomo’s fate deserves to be recorded.

Upon this prosperous little community [Ancona], disaster suddenly fell from heaven, in one of the most appalling tragedies in the whole course of Jewish history. In 1555, there ascended to the throne of St. Peter as Pope Paul IV the fiery Cardinal Caraffa, in whom the most fanatical aspects of the Counter-Reformation seemed to be personified. Notwithstanding all the solemn promises of his predecessors, the Marranos of Ancona were among the first to suffer from his religious zeal. On April 30, 1556, he withdrew the letters of protection and ordered immediate proceedings to be taken against [the Crypto-Jews]. The unfortunate victims promised to raise among themselves 50,000 ducats in order to secure a respite. They were, however, unable to secure the promised amount in time. Nothing, now, could save them. It was of no use for them to deny, even under torture, the fact of their baptism; since it was notorious that for the past sixty years no declared Jew had been able to live in Portugal. The persecution was carried out remorselessly. Twenty-four men and one woman, who stood steadfast to the end, were burned alive in successive “Acts of Faith,” in the spring of 1556, their martyrdom being celebrated in several poignant elegies. . . Contemporaries were struck especially by the heroism of the venerable Shlomo Ibn Yahya, who proclaimed his faith undauntedly from the scaffold. [12]

Of Yosef’s sons, David became President of the Naples Jewish community and resided there until his death. Yehuda was born in Imola in 1529 and studied medicine at the University of Padua. That institution had a tradition of being open to Jewish thought. Rabbi Elijah Delmedigo had held a chair in philosophy at the university and had been a major influence on Pico della Mirandola, the famous Florentine philosopher and Renaissance poet. Padua was also the “seat of a famous academy of Jewish learning as early as the fourteenth century, and its Jews were of high social standing, renowned for their learning and wealth.” [13] Yehuda studied at this yeshiva under the famous Rabbi Meir Katzenellbogen, the same rabbi who had eulogized his grandfather. R’ Meir had arrived in Padua circa 1506. He quickly established a reputation for scholarship and after studying with Rabbi Yehuda Mintz Halevi received his rabbinical title. R’ Meir Katzenellbogen rose to be a revered leader and was known as MaHaRaM miPadua. Yehuda Ibn Yahya could find no better teacher of his Judaic heritage. Yehuda received his medical degree in 1557, already well versed in Talmudic learning. He practiced medicine in Bologna for three years until his death. He was known as Yehuda ha-Rofe.

It is through Gedaliah Ibn Yahya ben Yosef that the line continues. Gedaliah was a banker and Talmud scholar from Imola where he was born in 1515.

He studied in the yeshiva at Ferrara under Jacob Finzi and Abraham and Israel Rovigo. In 1549 he settled in Rovigo, where he remained until 1562, in which year the burning of the Talmud took place in Italy. He then went to Codiniola, and three years later to Salonika, whence he returned in 1567 to his native town. Expelled with other Jews by Pope Pius V, and suffering a loss of 10,000 gold pieces, he went to Pesaro, and thence to Ferrara, where he remained till 1575. During the ensuing eight years he led a wandering life, and finally settled in Alexandria [where he died circa 1587]. His chief work was the Sefer Shalshelet ha-Kabbalah [Chain of Tradition], called also Sefer Yahya, on which he labored for more than forty years. This work is not without defects, having suffered either by reason of the author’s itinerant mode of life or through faulty copying of the original manuscript. Its contents are as follows:

1) history and genealogy of the Jews from the time of Moses until that of Moses Norzi (1587);

2) account of the heavenly bodies, Creation, the soul, magic, and evil spirits;

3) history of the peoples among which the Jews have dwelt, and a description of the unhappy fate of the author’s co-religionists up to his time.The value of this work is, however, lessened considerably by the fact that the writer has included many oral narratives which he gathered partly in his home, partly in Salonika and Alexandria, and that he often lacks the ability to distinguish truth from fiction. For these reasons the book has been called “The Chain of Lies.”; but [authorities have] proved that it is more accurate than many have supposed it to be. The Shalshelet ha-Kabbalah was published at Venice, 1587; Cracow, 1596; Amsterdam, 1697; Zolkiev, 1802, 1804; Polonnoye, 1814; and Lemberg, 1862. Gedaliah was the alleged author of twenty-one other works, which he enumerates at the end of his Shalshelet, and which are also mentioned in Ben-Jacob’s Ozar haHayyim. [14]

We must interject a word or two about the accuracy of Shalshelet ha-Kabbalah. {ספר שלשלת הקבלה בו מבואר סדר הדורות וקורות כל דור ודור, חיברו גדליה בן יחייא}. There are some inaccuracies in the genealogical account, but no more than in most of the documents we have reviewed. Certainly not enough to call this work “Chain of Lies.” It is an invaluable work which allows access to ancestral account of almost 500 years ago. Furthermore, the inclusion of oral narratives adds to its value. They lend color and a human perspective to otherwise dreary data. That is why I have included so many oral reminiscences in this work. Perhaps some critic a half-millennium in the future will fault me for that technique. With all the criticism, modern scholars have found Shalshelet ha-Kabbalah to be a crucial reference in tracing the generations of Ibn Yahyas back to its Davidic roots. In combination with other sources mentioned herein, it provides authoritative corroboration of the genealogies available to modern day researchers.

Gedaliah was married twice. His first wife died after giving birth to a son. Gedaliah second wife had five sons and a daughter. The marriage of Gedaliah’s children produced a prodigious expansion of the Ibn Yahya family. One of Gedaliah’s sons, Yehuda, born circa 1540, had four sons of his own. Yehuda’s grandson, Eliezer Ibn Yahya ben David, born circa 1585, like his father and grandfather, was a rabbi in Constantinople and Salonika. He was invited to assume a rabbinic post in northeastern Poland in the early seventeenth century. It is this Eliezer who was accorded the title Chacham Rosh L’golei Polin, or Charlap, in honor of the first Charlap, Chiya al-Daudi. With the move of Eliezer into Poland the Sephardic Ibn Yahya family was to blend with the Ashkenazi community of Suwalk, Lomza, and Grodno Guberniyas to establish the Charlap dynasty prominent rabbis.

A variation of the Charlap entry into Poland is offered by Avi Harlap. He writes that a careful study of Eliakim Carmoly’s history of the Yahya family indicates that Gedaliah did not die in Alexandria, Egypt, but in Alessandria, a town sixty to seventy miles northwest of Genoa, Italy, along the road to Turin. Avi believes the available records show that Gedaliah’s descendants stayed in Italy until the early seventeenth century when they left Padua for Tykocin {Yiddish: טיקטין, Tiktin; Russian: Тыкоцин; German: Tykotzin}, Poland. Joining them on this journey was Saul Katzenellenbogen, a descendant of the Maharal, Rabbi of Padua. [15]

It is true that many of Gedaliah’s descendants were living in Italy in the seventeenth century. Indeed, they continued to live there right up to World War II and even to contemporary times.The name Ibn Yahya survived with variations and some in the family even assumed the Charlap name. As recently as 1900, a painter and sculptor, Guy Harloff, had a studio in Galliate. [16] During the Mussolini period, Ibn Yahya descendants were active in the opposition.

Mario Yacchia, born in 1896, was a decorated veteran of World War I and a veteran anti-fascist who together with others, such as Fari and Amendola, founded the Committee for National Liberation and organized the group Freedom and Justice. He was commander of the partisans in the region of Emilia. Once, while attending a meeting of partisans in Parma, the gathering was betrayed by an informer and the house was surrounded by the enemy. He could have saved himself but he saw to it that the other escaped. Then he began to destroy important party documents. He was caught and tortured but maintained silence. On August 20, 1944, he was shot. The government posthumously awarded him the golden medal for Bravery. [17]

While it is agreed that Ibn Yahyas continued to live in Italy, the question of where Gedaliah died is open to interpretation, although more recent scholarship than that of Carmoly asserts that he spent his last days in Alexandria. However, there is no doubt that he travelled to Salonika and Alexandria and recorded his observations about Jewish communities in the region. Many of his cousins, Ibn Yahyas descendants from David ben Shlomo, were successfully ensconced in Turkish territory and Gedaliah had warm reunions with them. Nor is there any question that Gedaliah’s son, Yehuda, served as rabbi in Ottoman controlled lands and that Yehuda’s son and grandson, David and Eliezer Ibn Yahya, continued as rabbis in Salonika and Constantinople. This does not conflict with Avi Harlap’s assertion that other Ibn Yahya descendants had continued in Italy and left from Padua for Tykocin as stated. Quite the contrary, it tends to fill in missing details. It seems likely that if Eliezer assumed an important rabbinic post in Poland, his cousins from Italy might join him.

Tykocin was going through an extraordinary growth period in the early 1600s. It was engaged in struggle with nearby Grodno for economic and political dominance of the region. Earlier, Tykocin had been associated with the Jewish Council of Lithuania, but in 1623 it severed those ties and swore allegiance to the Council of the Four Lands, the quasi-governmental organization that managed Jewish affairs in Poland. Tykocin was soon given jurisdiction of the Jewish communities ranging from Semiaticzi and Miedzyrzecz in the south to the borders of Suwalk in the north. Including were the communities of Brainsk, Wysokie Mazowieckie, and Ciechanowiec, all to become centres of the Ser-Charlap family. [18] It is to this region that Eliezer and other Ibn Yahyas from Italy and Turkey migrated. The Katzenellbogen family who, according to Avi Harlap, had come into the region with the Ibn Yahya/Charlap group, maintained their prominence in Tykocin. Saul Katzenellbogen, known as Saul Wahl {רבי שאול וָאהל קצנלנבוגן}, lived mainly in Brisk and was closely connected with the royal family of Poland. There is a preponderance of evidence that indicates that Saul was appointed “King for a Night.” His son, Rabbi Meir Wahl, known as the MaHaRaSh, served as head of the Bet Din in Tykocin. [19]

Eliezer and his coterie were not the only Ibn Yahyas who had found their way into eastern Europe. Even before the expulsion of the late fifteenth century, Spanish and Portuguese Jews were plying the trade routes to the East through both the Mediterranean and Baltic Seas. Other Jews sailed south around the Cape of Good Hope with Vasco de Gama. Jewish settlements began to spring up in ports along these routes. Ancient Jewish communities had already existed along the Mediterranean route in North Africa, Sicily, Italy, Greece, and Turkey. With the Age of Exploration international trade flourished and Jewish shippers and bankers from Iberia were in the forefront of the newer enterprises. When ecclesiastical tyranny forced the Jews from Spain and Portugal it was natural for them to seek haven in the trading outposts with which they already had commercial alliances and bonds of blood. Many of the exiles fled north to Belgium, Holland, and Germany. Portuguese Jews flocked to Antwerp and through their business acumen transformed that city into the most important Belgian port, replacing the beautiful medieval city of Bruges. Others settled in Altona, near Hamburg. Other Sephardic families ventured further east along the Hanseatic trade route and established presences in Lubeck, Danzig, and Memel. As the Spanish hold on Holland weakened during the 1500s, Jews and Marranos showed up in Amsterdam. By the latter part of the century

the capital of the little republic became known as the Dutch Jerusalem. . . [The Jews] were mostly wealthy, enterprising, and highly cultured. Opportunities which had been denied in Spain were eagerly grasped in Holland. The Jews became interested in the carrying trade, and their capital helped build up the Dutch East and West India Companies, which, as if in retribution, were the chief instruments in the destruction of Spanish and Portuguese commercial supremacy. Rembrandt’s many portraits of Jewish worthies are a significant tribute to the comfortable and influential positions attained by the erstwhile exiles. [20]

While this dispersion was taking place, Poland was developing into a great power. In 1525, under King Sigismund I, Poland had extended hegemony over Prussia, and was soon to incorporate Latvia and Estonia. Within a few decades the Polish throne would control a vast area from the Baltic to the Black Seas. The eastern city-states of the Hanseatic League fell under Polish influence. On the other side, the Poles were the protector’s of Europe’s southern flank, repeatedly threatened by the Turks. To ameliorate the latter concern, trade alliances were periodically arranged with the Ottoman Empire. At the time, the Polish regime was one of the strongest and most liberal in Europe. “In its better period it allowed a genuine equality to the other races and extensive self-government to some of them.” [21] That atmosphere attracted Jews from the south and the northwest. Some, like Eliezer Charlap came from Turkey. Others who had migrated to the Baltic city-states found Poland to be a hospitable respite after generations of wanderings. The Jewish population of Poland multiplied by a factor of six during the sixteenth century. The growth was not only due to a natural increase in the Ashkenazi population. “Its numbers soared in the decades after the expulsions from Spain in 1492 and Portugal in 1496.” [22] Adding to this increase were Ibn Yahyas who had entered Poland through the Baltic route. Along with Charlaps, they appear in early records of Jewish communities in towns where trading was an important economic factor.

One such town was Vilkaviskis (Vilkovishk) in what is now Lithuania. Jews established themselves there shortly after the expulsions from Iberia. They kept accurate records of the community and as recently as 1920 a massive tome containing information about 400 years of Jewish life in Vilkaviskis was cited by several researchers. This book, which contained references to the Ibn Yahya and Charlap families, had been in the possession of Dr. B. Brutzkes. It was stolen or destroyed by vandals in the decade after World War I. [23]

This book indicated that a Jewish settlement existed here at the beginning of the sixteenth century. Further historic proof lies in the fact that at the beginning of the sixteenth century Princess Bora Sforgas, wife of Sigmund August II, made a gift of lumber to the community to build prayer houses and the copper domed synagogue, known to its last days as “The Old Shul.” Its Ark, three stories and eleven meters high, was decorated with rare carvings of animals and housed the profusely embellished Sefer Torahs which originated in Spain. [24]

We have already mentioned that, under Christian rule in Spain, some Ibn Yahyas changed their name to Don Yahya. In northern and eastern Europe the name often was altered to give it still more of a native sound. Don Yahya became Dongin, Donchin, Dionis and a myriad of variations. The original name of Alvaro Dionis (Diniz) was Shmuel Ibn Yahya. He had been master of the mint in Altona and Gluckstadt, near Hamburg. Diniz (also known as Alberto de Nyes) “maintained one of three local synagogues in his house. [He] was the author of an abortive scheme to procure a settlement of Portuguese Jews in the kingdom of Bohemia. His descendants were the financial agents to the Dukes of Gottorp (Schleswig-Holstein) and to the Danish crown.” [25]

By 1605, Diniz had established his main office in Hamburg with branches in Lubeck, Gdansk [Danzig] and throughout the Polish countryside. His business partners, Dirichsen and Gabriel de Valenca, moved to Danzig. In 1622, King Christian IV of Denmark granted Diniz’ firm a monopoly on the import of baysalz or boysalz, a salt from the Bay of Biscay, highly prized throughout the region. . . In the eighteenth century, descendants of this family lived at Lozdzieje [Lazdai] and Bakelarzewo [Baklerowe] in Suwalk Guberniya of Poland. Some members engaged in the salt trade and were known by the surname of Bejm (from baje, the Polish spelling of bay). The name Diniz was used as a given name, particularly for women (Dina). . . a Dina Ibn Jachia fled the Iberian Peninsula with her family and settled in Italy; the Charlap pedigree descends through her to a great-grandson who settled in Poland. . . The combination of Italian and Dutch elements in his [Diniz] correspondence permit us to assume that he was in the Netherlands and in Italy before coming to Hamburg. [26]

The implication here is that Diniz (Shmuel Ibn Yahya) was related to Dina, wife of David Ibn Yahya ben Yosef. This conclusion appears justified from my research and analysis. Susan Sherman has provided a major service with her Avotaynu article; that is, to draw attention to the fact that the gap between Ashkenazi and Sephardic Jews is somewhat artificial. No Jew from Poland or Russia can state with certainty that he has no Sephardi ancestors. The different traditions of the two groups arose from their varied geographical locations but all Jews are in reality one people. Ms. Sherman has made one error. She states that the Charlaps descend from Dina’s great-grandson who settled in Poland. She is two generations off; Eliezer Charlap was the great-great-great-grandson of David and Dina Ibn Yahya.

The fact that Don Yahya was changed to a Slavic sounding name in Russia did not sit well with the more traditional in the family. The following letter from Chaim Rafael Don Yechiya illustrates that point.

To the grandson of my brother Shlomo, whom I do not know personally, but whose letter was as if I see him before me, I send my best greetings; that is to Mr. Leib Don Yechiya. . . He has demonstrated that the glory and pride of our great family is not to be forgotten, but will be remembered by our children so that they will always remain in contact with their relatives. Thus correspondence will serve to fill in for face-to-face meetings. Vast distances need not separate the closeness of our hearts. Now I will state a few facts to reveal some things, hidden deep within us, but are as yet unknown to him. He is still young in days and for want of time has not yet sought knowledge from books (as each should do) to learn of his ancestral roots – the family and tribe of which he is the offspring. My thoughts give me no rest and I am fearful that the pride of our family will diminish during the course of days. Hence I state herewith my heartfelt emotions. I trembled upon seeing his name signed as Donchin. I immediately understood that he had a lack of understanding of our family, as it is called in our tongue nazwisko [family name]. I will apprise him of what I learned from books – one Shalshelet ha-Kabbalah that traces all the way back to Yehuda, son of our Patriarch Yaacov. The second book is Seder Hadorot Hagadol. There it is stated that our family is descended from King David. Therefore, be it known to you, my kin, that our family is neither from Russia nor from any other nearby European country, but from Spain, the land from which we have been outcast for hundreds of years. Our forefathers commanded us to retain our name, to preserve it through the generations, and none dared change it. As it is said in Seder Hadorot – Don Yechiya was a minister in Spain before the outcast; his son became commander-in-chief of the entire army in Portugal. All the generations that followed were famous rabbis and people of wealth up to my father Menachem Mendel. He was the tenth generation to Rabbi David of Deneburg. After Menachem Mendel comes my brother Abraham. Even now, thank the Lord who does not remove his kindness from us, we have six famous rabbis from my father’s brother, Rabbi David, Rabbi Shalesy of Drisso, with two brothers who are rabbis in Shos and in Ullah, and then the three sons of Rabbi Shalesy. So let it be known that our nazwisko is Don Yechya, as stated. Knowing thus the righteous descent of our family; that they were religious, famous, respectful ministers who did not forsake our Law, he too will follow the path of his ancestors and will pay no heed to evil companions who are false to their religion and people. May he always remain true to his people and pride be with him always. This letter is meant as a Purim present, as I have no other gifts. He shall store it with his treasures and, in the course of days, sons and daughters will be born unto him and this may be of some aid to them. [27]

In August of 1989, Nancy and I met Trudy Donchin Chityat at a gathering hosted by Dick and Julia Hyman. Trudy had been researching her family roots for some twenty years and was in contact with Chaim Freedman of Petah Tikvah. Freedman was heavily involved in a research project documenting the descendants of the Wilna Gaon. The correlation of our records, coupled with results of Neil Rosenstein’s research into prominent rabbinic clans, yielded some interesting relationships. These indicate that the Charlap connection to the Don Yahya family is even closer than the direct descendance of Eliezer, the first Charlap of Poland.

The daughter of Elijah, the Wilna Gaon, was Pesche Batja, wife of Rabbi Zvi Hersh ben Yitzhak Donchin. [28] The antecedents of Yitzhak Donchin have not as yet been discovered but every appearance of that name indicates descent from the Ibn Yahya family. This branch of the Donchin family lived in Disna, Wilna Guberniya. The town is west of Polotzk between Dvinsk and Vitebsk. We know of two sons born by Pesche Batja: Yitzhak and Shlomo Zalman. Yitzhak, grandson of the Wilna Gaon, married Chana, almost certainly his cousin. Chana was the daughter of Baruch Don Yechiya, son of Yeshayahu Shapiro, who lived in Nikelsburg, Germany. Prior to that, Yeshayahu most likely lived in the Bavarian city of Speyer. Fearful of persecution he assumed the name of the town. Jews in German city-states and in Prussia generally assumed family names earlier than their co-religionists further east. Many families bearing the names Shapiro, Spira, Speier, et al originate in the region of Speyer. In 1750, or thereabouts, Yeshayahu settled in Uschatz, Vitebsk Guberniya. There he became wealthy and devoted much of his later life to Torah scholarship. In 1804 Baruch restored the Don Yechiya name when authorities forced Jews to assume surnames. Baruch, one of the greatest Torahscholars of his age, became a rabbi in Disna after studying with his father-in-law Rabbi Yosef Shlomo of Hozenfot, Kurland. R’ Yosef Shlomo was also a descendant of the Ibn Yahya family, his father being Menachem Don Yahya. [29]

Several references state that Yeshayahu was the son of Ephraim Eliezer Zvi Hersh Charlap. [30] A manuscript fragment from Jack Chodoroff of Toronto was said to originate with his father. It closely resembles some of the wording in L’Toledot Yishivat Ha-Yehudim V’Kurland.

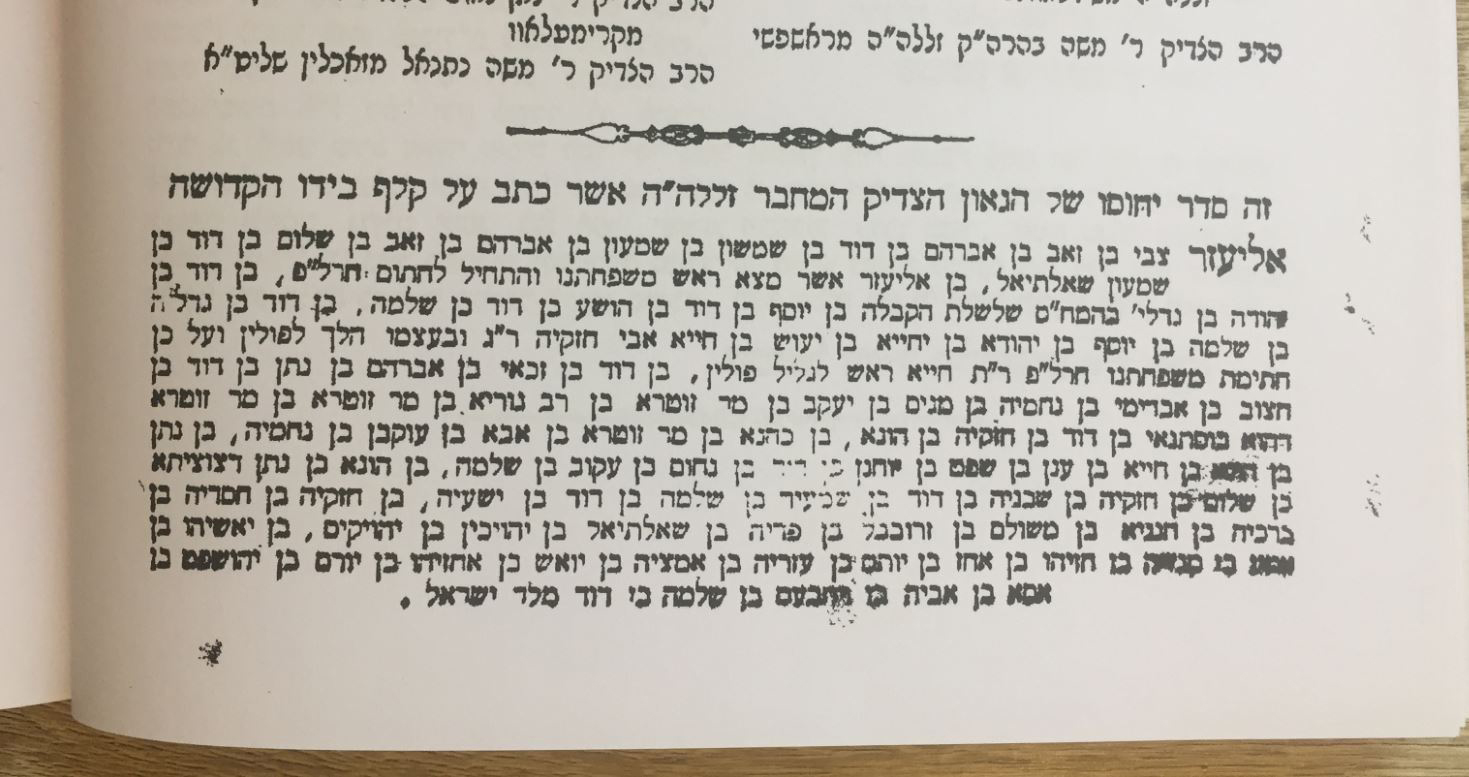

R’ Baruch, before he came to his father-in-law R’ Shlomo was known as Shapiro and through his father-in-law received the nick-name Don Yahya. This was about the time of his marriage. R’ Baruch was the son of the great and wealthy R’ Yeshayahu who was born in Ninsburg, but left for the city of Uschatz in Russia. There, he was to study with the great Gaon Rabbi Ephraim Eliezer Zvi Hersh Charlap. In the book Hod Tehilah, R’ E. Z. H. Charlap showed the pedigree of generation after generation from himself to King David. [31]

Family Tree (list of names) in ‘Hod Tehilah’, by Ephraim Eliezer Zvi Hersch Charlap, Rabbi of Mezeritch, first published in 1899. Photo © Gil Dekel, from a copy of the book purchased by Gil Dekel in 2021.

Jack Chodoroff had a version of the Charlap family tree which differed a little from the one that was published in Hod Tehila. These differences have been discussed in Chapter XXV. What is of interest here is that he also had a later connection between the Charlaps and Don Yahyas. The above fragment does not claim that Ephraim Eliezer Zvi Hersh Charlap was related to Yeshayahu Shapiro. However, combining it with the other sources mentioned and noting the future repetition of the name in both Charlap and Don Yahya lines, there is a high probability that Yeshayahu was descended from Charlaps.

But whom? We have two prominent Charlaps whose names match reasonably well. They have already been mentioned. One was Ephraim Eliezer Zvi Hersh ben Zev who lived circa 1785 to 1849. The other was {his grandson:} Ephraim Zvi ben Yosef Shlomo, the renowned Zionist who was in his nineties when he died in Israel in 1949. Neither of these men could possibly have been the father of Yeshayahu. As we have pointed out, the name Ephraim Eliezer Zvi Hersh, or similar combinations, shows up repeatedly in both the Charlap and Don Yahya families. For a person with that name to be Yeshayahu’s father he would have been born circa 1700. We have no record of such a person. However when we get back to the generation of Abraham Charlap, father of our modern tree, we have only the patrilineal descent. For example our Ephraim Eliezer Zvi Hersh is the son of Zev who is the son of Abraham. We know of Zev’s siblings, but have none for his father. From Abraham back, we have only a line of fathers until we get to the Ibn Yahyas of Spain. Between Eliezer Ibn Yahya, who became Eliezer Charlap, and Abraham Charlap we have no lateral relationships. I hypothesize that our Ephraim Eliezer Zvi Hersh ben Zev, Gaon of Mezritch (Miedzyrzec) was named for a great uncle, an older brother of Abraham Charlap. It is this person who would then be the father of Yeshayahu. That is the only logical explanation if we accept the authenticity of the sources which name Ephraim Eliezer Zvi Hersh Charlap as the father of Yeshayahu Shapiro. This hypothesis is substantiated by the discovery that Yeshayahu had a brother David ben Ephraim Eliezer Zvi Hersh Charlap who was married to a Yente bat Natan Matityahu. [32] Like his father, David does not appear on any of the modern family charts. He comes from the lateral extension of the generation of Abraham Charlap. The older Ephraim Eliezer Zvi Hersh, like his later namesake, was a rabbi in Miedzyrzec. [33]

Considering the above, it is interesting that in 1804 Baruch assumed the Don Yechiya name, rather than Charlap. As a distinguished scholar and rabbi, he knew well that the Charlaps descended from the Ibn Yahya family. Furthermore his father-in-law was a Don Yahya. It would be a hearkening back to the traditional roots and a joining of his children’s two ancestries by restoring the name to Don Yechiya. [34] Baruch’s four known children were the aforementioned Chana, and Menachem Mendel, David, and Freida. Menachem Mendel ben Baruch was acclaimed as one of the great Talmudic scholars of his time. He was affectionately known as Menke Vidzer as he was rabbi in the shtetl of Vidzizh. Of his three sons, we know that Avraham was rabbi in Deneburg. Chaim Rafael ben Menachem Mendel was the author of the letter to Leib Donchin which was quoted earlier. Moshe ben Chaim Rafael became rabbi in Cholma, Peskov district. Menachem Mendel’s brother David was a rabbi in Disna. His grandson Shabtai ben Chaim was a rabbi in Drissa for sixty years. He had married Malka bat Naftali, the Gaon Rabbi of Ludza. Shabtai was congenial with the Chabad movement and was considered a Hasid. He was the author of many responsa and was known as the “Ancient Sage.” Shabtai was not the only Don Yechiya to become a follower of the Lubavitcher Rebbe. His cousin Eliyahu Zvi Hersh, son of Yitzhak and Chana, was also a member of Chabad. Hence the great-grandson of the Wilna Gaon, a hero of the Mitnagdim, became a Hasid.

Shabtai’s brother Zev also joined the rabbinate and became head of the Bet Din in Uschatz. Their brother Shlomo held a similar position in Ullah and another brother, David, was Rosh Yeshiva in Polotzk. Their sister Dina married Avraham Kudritzin, from a family which has many interconnections with the Don Yahyas.

Yehuda Leib Don Yahya was one of the notable descendants of Baruch ben Yeshayahu. He was born in Drissa in 1869 and in 1902 began his service as a rabbi to a variety of Russian communities. While still a yeshiva student he was attracted to Zionism and was disturbed that many traditional rabbis did not share his views. Yehuda Leib recognized that it was the Jewish religion itself which was the most important basis for political Zionism. Without the religious tradition Jews would have no claim on Eretz Yisrael. He tried to spread the views of his proto-Zionist predecessors, Rabbi Yehuda Alkalai and Rabbi Zvi Hirsch Kalischer. He became a follower of the great Rabbi Shmuel Mohilewer and saw Zionism as the natural culmination of the history of the Jewish people. Though there were many secularists among modern Jewish Zionists, Yehuda Leib believed that the underlying emotions were religious in nature. What was needed was “not mere traditional piety about the Holy Land but a conscious blending of orthodoxy in religion with modern Jewish nationalism.” [35] In 1901 Yehuda Leib published Ha-Ziyyonut mi-Nekuddat Hashkafat ha-Dat (Zionism From the Religious Point of View). In this work, which was widely distributed and read, he preached to the religious community that political Zionism and settlement in Eretz Yisrael were religious duties. In 1893 Rabbi Mohilewer had established a new center to spread the budding Zionist message in the Orthodox community. In 1901 this effort was expanded into the Mizrahi movement by four rabbis including Yehuda Leib and Jacob Reines. Yehuda Leib was a religious Zionist throughout his life, even during the Stalin era in Russia. He made aliyah in 1936 and settled in Tel Aviv. Yehuda Leib Don Yahya was extremely conscious of his debt to preceding generations.

I wish to record memories of that which I heard from my father, the Gaon Rabbi Chaim Don Yahya, son of the venerable Gaon Rabbi Shabtai Don Yahya. The father of R’ Shabtai was R’ Chaim and the name of his father was R’ David. Both were righteous men and worked day and night over the Torah. Neighbors held them in awe and would ask, “When does R’ Chaim sleep? We see him studying day and night.” R’ David, father of R’ Chaim, lived in the city of Disna. When he died the entire town mourned and the people cried for they had lost more than a Torah scholar. R’ David was a true hasid who performed mitzvot in a special way. The way he showed compassion for the sick would have to be seen to be believed. R’ David’s father was the Gaon Rabbi Baruch Don Yahya, rabbi in Disna and the Galil The father of R’ Baruch was Yeshayahu, a man wealthy and schooled inTorah He came from Nikelsberg in Ashkenaz and settled in Uschatz in Vitebsk Guberniya. The father-in-law of R’ Baruch was Rabbi Shlomo of Hozenfot, Kurland. A very popular and respected sage, he left behind a written manuscript of [religious interpretations]. His grandson, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Don Yahya, attempted to publish it but the manuscript was stolen. Menachem Mendel, the son of R’ Baruch, was a genius and a beloved rabbi known as the Menke Vidzer. All of this I heard from my father, the Gaon Rabbi. I also learned from my father that we are descended from the Don Yahya family of Spain and, as we know, they are from the House of David. [36]

The Don Yahyas spread out from Suwalk and Lomza Guberniyas, the area that traditionally was home to our family during our sojourn in eastern Europe. They had moved into Latvia via the eastern Hanseatic cities and from there moved east into Byelorussia and south to the area of Miedzyrzec. Ludza in eastern Latvia had a Don Yahya presence for several generations. In 1847 this town, part of Vitebsk Guberniya, was home to 2,299 Jews, a majority of the population. Most were shopkeepers and artisans but there were a substantial number of famous scholars and rabbis. Among the latter group were Don Yahyas and the closely associated Zioni and Kudritzin families.

Eliezer ben Shabtai Don Yahya, author of responsa on the Shulhan Arukh, Even Shetiyyah (1893), was a disciple and son-in-law of Aaron Zelig Zioni and his successor in the rabbinate of Ludza (1870-1926). Eliezer’s son, Ben Zion, was the son-in-law of Isaac Zioni, and for twenty-six years officiated as rabbi in Vilaci; after the death of his father he succeeded him in the rabbinate in Ludza (1926-1941), Ben Zion, who perished in the Holocaust, was the author of halachic books and historical articles. Because of the high standard of Jewish learning the community was known as the “Jerusalem of Latvia.” [37]

Ben Zion not only married a Zioni, his mother was Elka Zioni. Moreover, his sister Malka married Yisrael Zioni. Ben Zion’s family was decimated in the Holocaust but three of his six children survived. Yitzhak, Moshe Gershon, and Baruch Rafael were martyred, but son Aharon escaped east to Russia and after the war became a railway engineer. The other brothers, David and Shabtai, made it to Israel where they prospered and produced accomplished families. David studied in the Merkaz Ha-Rav Yeshiva and was a teacher in Kfar Hasidim and Kiryat Yam. Shabtai, studied under the leading rabbis of Israel and received ordination. He was active in Hapoel Hamizrachi and became a writer and journalist. In 1948 Shabtai was appointed editor of the newspaper Hatzofeh and served in that position for thirty-two years. His books include Be’ohlei Torah Va’avodah [In the Tents of Torah and Labor], Anshei Torah Vemalchut [Community of Torah Kingdom], Hamered Hakadosh [The Holy Revolution], and Be’ol Ha’asiya [In the Yoke of Action]. Shabtai’s children are Ben Zion (Benny) Don Yechiya and Ruth Charif, developers of the Don Yechiya family tree.

Let us return now to the family of Yitzhak Donchin, grandson of the Wilna Gaon, who married Chana bat Baruch Don Yechiya. Their son Eliyahu Zvi Hersh had three known children: Shmuel, Lifsche, and Meir. Lifsche married David Shlomo Kosovsky (Shacor). We will talk about the Kosovsky connection shortly. Shmuel, a merchant, married Rachel, whose family name remains in doubt, and had two known sons. His son Eliyahu Zvi earned his living as a merchant in Warsaw, but his genetic disposition toward scholarly pursuits is evidenced by many published articles on Judaism. Eliyahu Zvi took as wife Minda, daughter of Shaul Kosovsky. They had many children, one of whom was named Lifsche and like her predecessor for whom she was named, married a Kosovsky – the attorney David Shlomo. This family has produced many Sabra progeny.

Meir, grandson of Yitzhak and Chana Donchin, married Zisle Mera Fein. Two of their daughters married into the Kudritzin family. Their two sons, David and Nathan (Nuchim), also married and gave rise to large families. Some of David’s children dropped the final letter of the Russified name and were called Donchi. Among Nuchim’s eight children was Baruch. Baruch is the grandfather of Trudy Donchin Chityat.

From what I can gather from my uncle Mayer (Meir) Donchin, the family lived in the small Lithuanianshtetl of Pikalen. There was terrible anti-semitism and pogroms finally convinced them to leave. My great-grandfather, Nuchim, was the first to go. He settled in New York and some of his children followed him. My grandfather was not so adventurous. Sweden seemed a much closer haven. He settled in Lund, near the southwestern tip of Sweden. It was a pretty town just outside of Malmo and across a narrow strait from Copenhagen. There was an active Jewish community in town. I was told that a few streets were almost totally Jewish. There was no feeling of isolation. The Jews had very good relationships with their Swedish neighbors but they could also pursue the Jewish religion, follow their traditions, and live in peace. In 1909 Grandpa Baruch received word that Nuchim had died in New York. My great-grandmother Dvora Matl, then known as Matilda, had survived her husband. I guess Nuchim’s death prompted my grandfather to join his relatives in New York. He came in 1911. I knew that there were some families that were very close to the Donchins: the Kudritzins, Kosovskys, and Zionis. There was one example where three successive generations of Donchins, really Don Yahya, married Zioni relatives. Shabtai Don Yahya married Malka; then their son Eliezer married Elka Zioni; and then two of Eliezer’s children married Zioni’s. Ben Zion Don Yahya married Chaya Zioni and Malka Don Yahya married Yisrael Zioni. A few years ago, I met the daughter of Yisrael and Malka in Brooklyn. Her name was Tzipora, or Faiga in Yiddish. I learned that Ben Zion had perished in 1941 at the age of seventy. There is an extensive family in Israel and though the original community in Ludza was destroyed by the Nazis, the best answer is to lead fruitful lives and that means having Jewish families. [38]

Trudy Donchin Chityat has sought out Don Yahya relatives around the world. Her correspondence with Yaacov Kosovsky-Shacor of {the city} Bnai Brak {Bnei Brak}, Israel, has pertinence to our investigation. Yaacov is a direct descendant of the Don Yahya family that stems from Elijah, Gaon of Wilna. His grandmother was Lifsche Donchin who married David Shlomo Kosovsky, an advocate. David Shlomo and Lifsche had two sons and a daughter. Minda Kosovsky married Rabbi Naftali Bar-Ilan. Her brother Emanuel, also a rabbi, married into the Yisraeli family. The third sibling, Shaul, was a rabbi and lawyer. He married Varda Cohen and had four children before dying at a young age. One of Shaul’s children is Yaacov Kosovsky-Shacor.

The Kosovsky-Shacor family values traditional Judaism. This is reflected in Yaacov’s interest in his roots. He has been researching the Donchin/Don Yahya family and was planning a book about his family tree. That tree conforms closely with other Donchin genealogies but Yaacov also had difficulty with the Don Yahya-Charlap connection.

I have made a deep investigation into the background of our ancestor R’ Baruch Don Yahya. I could find no connection with Gedaliah Ibn Yahya, author of Shalshelet ha-Kabbalah. Baruch is apparently from another chain of the Don Yahya family. A while back I sent a long list of generations from Baruch Don Yahya, the head of my family, dating back to King David. That listing was a mistake based on a misinterpretation of several books. It is true that R’ Ephraim Eliezer Zvi Hersh Charlap can be traced back to King David through the Ibn Yahya family. But for R’ Baruch ben R’ Yeshayahu, I have only the Don Yahya/Donchin tree. It is possible that Baruch stems from the same Charlap branch but I don’t know how. There is no clear indication as to how he fits into the main trunk. [39]

Yaacov’s reservations about the ancestry of R’ Baruch are well-taken. However, even if the previously presented hypothesis concerning an earlier Ephraim Eliezer Zvi Hersh Charlap is incorrect, there is no question that the Donchin/Don Yahya family stems from the same “trunk” as the Charlaps. The only question is the point at which their stem branches out.

Trudy’s search led to the discovery of other eastern European descendants of the Ibn Yahya family. Herman Reitman wrote:

My great-great-grandmother Yetta Jechia (circa 1805) married a maternal ancestor of mine, Leibel Trenner. The Trenners resided in Cracow, continuously from about 1750 to the Holocaust. Dr. Neil Rosenstein indicates that Jechia relates to Don Jechia which relates to Donchin. [40]

Another correspondent writes, “My father was Baruch Zalkin Donchin of Vitebsk Guberniya. His brothers and sister emigrated to Chicago. My mother was an Arnstein from Suwalk Guberniya.” [41] From Chicago comes still another letter:

My husband’s father, Benjamin Donchin was born in Wilna Guberniya. At the age of thirteen he was apprenticed to a saddle maker in Riga, Latvia. He came to this country before the turn of the century and worked as a saddle maker for Marshall Field and Company. [42]

These are just a few examples of Don Yahya descendants who became “Ashkenazi” Jews in Poland and Russia. They are additional evidence that our ancestors from Spain and Portugal spread out, not only in the Mediterranean world, but also to northern and eastern Europe. As our research progresses, it appears likely that we will discover Ibn Yahyas who participated in the great Portuguese, Spanish, and Dutch discoveries during the Age of Exploration. Along a similar vein, all of our ancestors in Babylonia did not flee to Iberia. Some surely stayed in the Middle East or went east and north to such exotic cities as Bukhara, Samarkand, and Tashkent. Who among us can deny our relationship to the Jews of these far off lands? Once again, genealogical research highlights that the Jewish people are one big family.

Footnotes:

- Vivian B. Mann, Thomas F. Glick, Jerrilynn D. Dodds, eds., Convivencia: Jews, Muslims, and Christians in Medieval Spain (New York: George Braziller, 1992), p. xiii.

- Sources for the early Ibn Yahya genealogy are the fourteen family trees listed in chapter XXV; The Jewish Encyclopedia (1905); Encyclopedia Judaica (1971-72); Gedaliah Ibn Yahya, Shalshelet ha-Kabbalah; and Eliakim Carmoly, Sefer Divre Hayamim L’Bnei Yahya (Frankfurt-am-Main: 1850).

- Yitzhak Baer, A History of the Jews in Christian Spain, 2 vols., trans. Louis Schoffman (Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society, 1961), vol. 1, pp. 57-58.

- Abraham A. Neuman, The Jews in Spain, 2 vols. (Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society, 1942/5702), vol. II, p. 152.

- Judah Gribetz, Edward L. Greenstein, and Regina Stein, The Timetables of Jewish History (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1993), pp. 134-135.

- Baer, Op. Cit., vol 2, pp. 95-97.

- Louis Finkelstein, ed., The Jews: Their History, Culture, and Religion, 2 vols., (New York: Harper & Row, 1960), vol. 1, p. 236.

- David Goldstein, Hebrew Manuscript Painting (London: The British Library, 1985), p. 11.

- Ibid., p. 58.

- Advertisement placed by the Committee For the Recovery of Jewish Manuscripts, New York Times, October 12, 1988.

- Ibid.

- Cecil Roth, A History of the Marranos (Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society, 1941/5701), pp. 206-207.

- Neil Rosenstein, The Unbroken Chain, 2 vols., (Lakewood, N.J.: C.I.S. Publishers, 1990), vol. 1, p. 2.

- The Jewish Encyclopedia (1905), s.v. “Yahya; Gedaliah Ibn Yahya ben Joseph,” by Schulim Ochser.

- Letter, Abraham (Avi) Harlap to Arthur F. Menton, September 17, 1995.

- An obituary notice appeared in the New York Times between January 6 and January 10, 1990, stating that Guy Harloff had died on January 5.

- Massimo Adolfo Vitale, “The Destruction and Resistance of the Jews in Italy,” in They Fought Back: The Story of the Jewish Resistance in Nazi Europe, ed. Yuri Suhl (New York: Schocken Books, 1975), p. 302.

- Encyclopedia Judaica (1971), s.v. “Tykocin,” by Aharon Weiss.

- The story of Saul Wahl, King for a Night, was originally recorded in a 1736 manuscript by R’ Phineas ben Moshe Katzenellbogen, which is in the Bodleian Library, Oxford University. It then appeared in Zvi Hirsch Edelman, Gedullat Shaul (London: 1854). A Comprehensive genealogy and discussion of the Katzenellbogen family of this period is in Rosenstein, Op. Cit., pp. 3-11. Note variations in spelling of the family name.

- Abram Leon Sachar, A History of the Jews (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1965) p. 230.

- H. Haskins and R. H. Lord, Some Problems of the Peace Conference (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1920), pp. 167-197.

- Adam Zamoyski, The Polish Way (New York: Franklin, Watts, Inc., 1989), p. 75.

- Letter, Jack Chodoroff to Arthur F. Menton, January 17, 1990.

- Berl Kagan, Jewish Cities, Towns, and Villages in Lithuania (New York: privately published, 1991), p. 94. This translation from the Yiddish by Charlotte Wechsler was edited by Richard Allen Avner and appeared in Landsmen, vol. 5, no. 4, (Spring 1995), p. 3.

- Roth, Op. Cit., pp. 231-232.

- Susan C. Sherman, “Sephardic Migrations into Poland,” Avotaynu VI, 2 (Summer 1990): 15. Ms. Sherman refers to Hermann Kellenbenz, Unternehmerkrafte im Hamburger Portugal und Spanienhandel 1590-1625 [Entrepreneurial Power in the Trade Between Hamburg, Portugal, and Spain 1590-1625] (Hamburg: 1954), pp. 247-249, 388 no. 28, trans. By George Arnstein.

- Letter, Chaim Rafael ben Menachem Mendel Don Yechiya to Leib Donchin (Don Yechiya), January 4, 1920. Original text supplied by Dr. Neil Rosenstein.

- Family Tree of the Don Yechiya Family, Prepared by Ben Zion (Benny) Don Yechiya ben Shabtai and Ruth Charif, September 1988.

- Interview with Gertrude Donchin Chityat, Fort Lee, New Jersey, April 30, 1995. The intermarriage between these branches of the Don Yahya family was addressed by Yehuda Lieb Don Yahya, Bichurei Yehuda; but he reached no firm conclusion.

- Don Yahya/Donchin/Zioni family tree provided by Neil Rosenstein, January 14, 1993;

Dov Ber Owtchinski, L’Toledot Yishivat Ha-Yehudim V’Kurland (Generations of the Jews of Kurland, Latvia), 1908, pp. 75-76;

Letter, Neil Rosenstein to Arthur F. Menton, January 26, 1993 referring to Daat Kedoshim, p. 37;

Letter, Herman E. Reitman to Gertrude Donchin Chityat, July 28, 1983. - Interview with Jack Chodoroff, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, June 4, 1990.

- Charlap/Don Yahya/Donchin/Zioni chart provided by Neil Rosenstein, January 14, 1993.

- T. Eisenstadt, Daat Kedoshim (St. Petersburg: 1898-1899), p. 37.

- Again, we note that there are multiple spellings of the name. Many are transliterated from the Cyrillic, Yiddish, or Hebrew. The English spelling used herein conforms to that desired by current family members. The writer’s preference is Yahya.

- Arthur Hertzberg, The Zionist Idea (New York: Harper & Row, 1959), p. 399.

- Yehuda Leib Don Yahya, Bichurei Yehuda (Ludza, Latvia: Zev Wolf ben Yehezkiel Shoer, 1930-1939), pp.36-37, trans. By Eyal Peretz. Bichurei Yehuda could be translated as “First Fruits of Judah,” “Fruits of Judah,” “First Born of Judah,” or “Birth Right of Judah.”

- Encyclopedia Judaica, 1971-72 ed., s.v. “Ludza,” by Eli Davis. This source states that Ben Zion was a rabbi in Vilaci. Ben Zion’s grandchildren, Ben Zion Yechiya and Ruth Charif claim that he was “Rabbi of Marinhoiz in Latvia for twenty-six years.” Unless Marinhoiz and Vilaci are synonymous, this is contradiction.

- Interview with Gertrude Donchin Chityat, Fort Lee, New Jersey, April 30, 1995.

- Letter, Yaacov Kosovsky-Shacor to Gertrude Donchin Chityat, January 10, 1986; freely translated from the Hebrew by Ms. Chityat and Arthur F. Menton.

- Letter, Herman Reitman to Gertrude Donchin Chityat, July 18, 1983.

- Letter, Ella Donchin Bloomberg to Gertrude Donchin Chityat, December 18, 1974.

- Letter, Doroles W. Donchin to Gertrude Donchin Chityat, May 29, 1973.

Published on this site on 18 Jan 2021. Last updated 22 March 2021.

The book of destiny : תולדות חרלף = Toledot Charlap – Toldot Harlap – by Arthur F. Menton.

First published 1996. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y : King David Press. ISBN 0965444104.

Text © Arthur F. Menton and © Gil Dekel.

Images © Gil Dekel or © as specified.

Permission to publish on this website was granted from Arthur F. Menton.