Looking at one object and seeing different things: Joyce Raimondo interviewed by Gil Dekel

14 February 2024 – Vol 2, Issue 2.

Gil Dekel: Many artists say that they feel being a conduit, acting as ‘servants’ to bigger power or a purpose. It is as if the art is already ‘there’, and the artists’ job is just to bring it out.

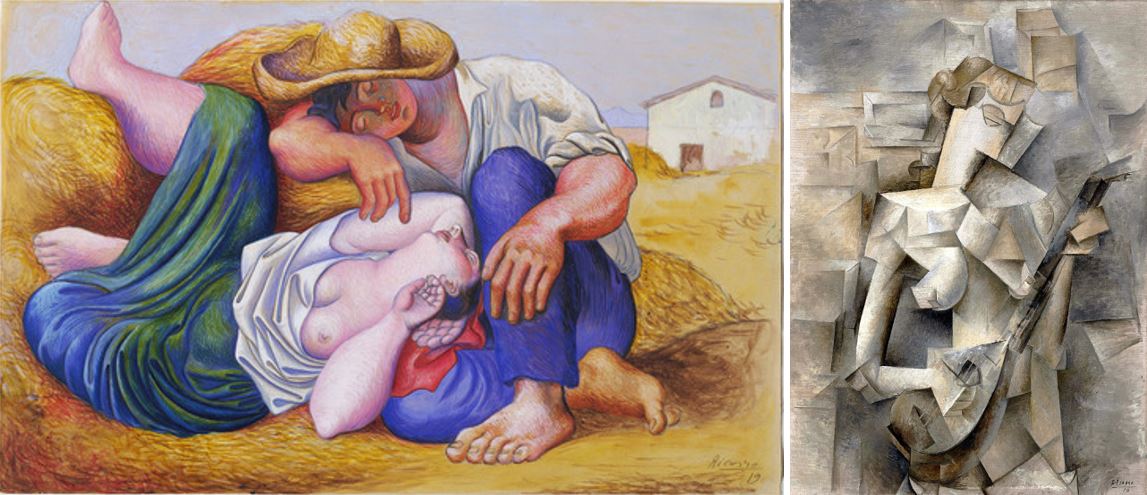

Joyce Raimondo: Yes, there’s a notion that runs through many artists that the artist is a vehicle, you might say, for a higher force. There’s a spiritual aspect to it, even if the artist doesn’t frame it in that language. For example, Michelangelo said that the image already exists in the sculpture, and he just has to remove the excess. Hilma af Klint, the abstract Swedish artist, said that a force moves through her. And Picasso said that he doesn’t know what the painting would become; it just comes through him.

In that sense, there’s the idea that an energy or a force is moving through the artist. In my opinion, the same is true in life. We are connected to an elevated higher being that moves through the human being. In visual art, this often manifests itself as a physical object. And in that way, it connects the viewer also to an elevated higher realm, you might say.

A force moving through the artist… Left: ‘The Swan’, No. 12, Group IX/SUW, by Hilma af Klint, 1915. Right: ‘Buddha’s Standpoint in the Earthly Life’, No. 3a, Series XI, by Hilma af Klint, 1920. Images in the public domain.

Gil: Did Jackson Pollock talk about being a conduit; about channelling his art?

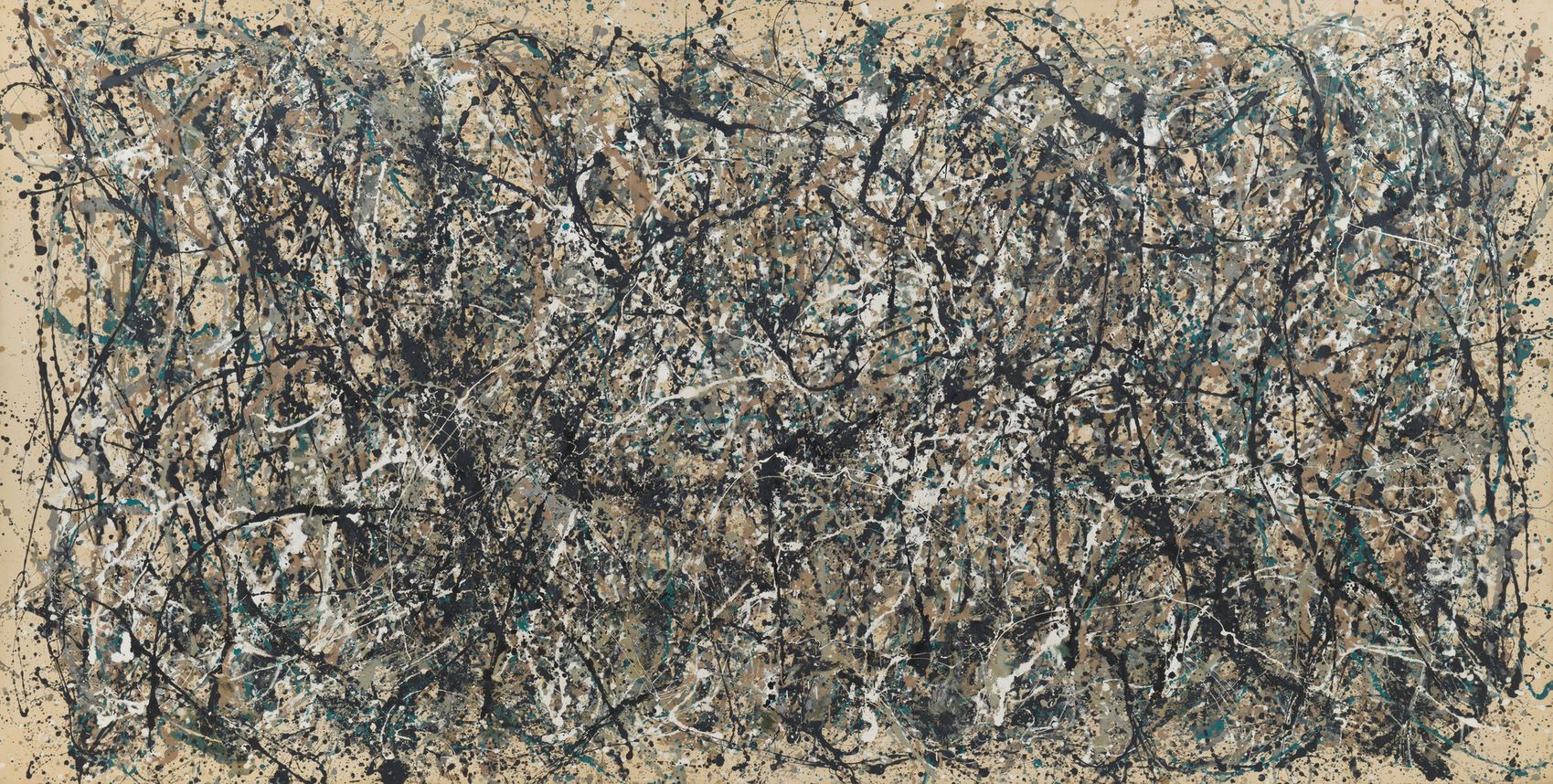

Joyce: Yes, but he didn’t phrase it in that way. He didn’t use the term channelling or the term conduit. He talked about the painting having a life of its own, and that he let the painting lead. He said that he wants to express his feelings, rather than illustrate them. He was invested in the idea of improvisational technique, where one mark on the paper leads to the next mark. He said that he can control the flow of paint, but not in the sense of pre-determining what the painting is going to be. It’s more like energy moving through him, through his inner being and subconscious, his emotions. So, in that way he is a conduit, you could say, but he didn’t use that term.

Personally, as an artist (and just a human being on this planet) I feel connected to a divine source. I feel that everything in my life is being guided by a divine force, everything, whether I am aware of it or not. As I get older, I realise that all the events of my life are meant to shape me as a human being so that I can give back through that divine inspiration. But if I’m talking about other artists, they may not necessarily frame it in that way. Each artist is extremely individual in how they think about their spirituality or speak about it.

‘One: Number 31’ by Jackson Pollock, 1950. Oil and enamel paint on canvas, 269.5 × 530.8 cm. © The Pollock‑Krasner Foundation ARS, NY and DACS, London, 2023. Permission to use was granted from DACS.

Gil: Are there any routines or rituals, not necessarily spiritual, that help artists open to inspiration?

Joyce: Now, a routine is something you do regularly. You could call it routine or call it an activity, even if you do it once. So, the question is: how do you spark creativity to access your inner power… The Surrealists wanted to tap into the unconscious, the inner life, and bypass the rational mind. But our rational mind is so strong that we need some techniques to bypass it. The Surrealists devised all sorts of games that you could play; all sorts of techniques to jog surprise. One of the most famous techniques is automatic writing, drawing and painting where you just paint or write without stopping. And you might not even look at the paper as you work.

To be an artist or a creative person, one has to nurture creativity. This is not a passive act. One of the ways to nurture creativity is to give yourself stimulation creatively and visually, by going for a nature walk, going to a museum, or even going into a retail store where you can see beautiful things. You could also simply do something you’ve never done before, or something that you don’t like to do. Do something you’re bad at, do something different. These activities can spark creative thinking. There are also all sorts of specific painting techniques. You want to get out of this mind that will keep going over the same thoughts over and over again.

Gil: There seems a contradiction about automatic writing. It is ‘flowing’, on the one hand, but on the other hand it is using words, which require logic and thinking.

Joyce: Yes, however when you do automatic writing, you don’t pause. And any thought that pops into your head, you quickly write it down. You just write continuously. This is an exercise I practise every day, writing in my journal; a little ritual I do while I’m having my coffee. I write in free associations. And I just let whatever is in my mind to come out. I don’t save them. When a notebook is done, I throw it out. This is a way of processing thoughts and even freeing up space in your brain. This is a good activity to do with all ages. You could do it with children as well.

I went into a school and did this exercise with third graders. One boy said: ‘I have a question, what if something inappropriate comes out?’ The students are told in school to be appropriate. And adults, too, want to be appropriate. We want to follow the constraints of society. So sometimes, to do this automatic writing and drawing activity, you must be a little bit open to see what might come out; maybe you’ll say something different. It is like dreaming at night, where not everything you dream is a pretty picture.

Gil: So, instead of trying to block experiences, we just need to open ourselves up to accept them…

Joyce: Yes. In different societies at different times, what was considered ‘appropriate’ can vary. Those are constructs that change in flux, but the artist is trying to tap into a deeper truth; into their own self-truth. It is not the ego self. No. It’s the pure Spirit. The Universal. These ideas which seem rather simple to us today, were actually really subversive in other times. It was like ‘I’m going away from what society tells me. And I’m going within my own truth.’

Gil: But is it not common for artists to ‘go inside’?

Joyce: Well, not necessarily. Some art serves society, and is not designed for individual expression. For example, the Sistine Chapel. Of course, Michelangelo was passionate about it, yet the art was made really to serve the Pope. It has specific symbols. Whereas someone like Jackson Pollock is working to express himself. Pollock was working in a barn, dripping paint. He’s not doing it to communicate a specific idea for a specific purpose, but rather to express his own feelings. In our modern times, the idea of individual expression and the rise of psychology, become acceptable and thus prominent in art.

Gil: Has this individualism, which is more accepted now than in the past, affected art production and the way we see art?

Joyce: It goes both ways, both in the production as well as the way we see art. When we’re looking at modern art, it’s open-ended. Marcel Duchamp said that the viewer completes the painting. Now, what does that mean that the viewer completes the painting? Beauty is in the eyes of the beholder, or meaning is in the interpretation of the viewer. There is no right or wrong way to look at an abstract painting. Jackson Pollock said that he wanted his paintings to be enjoyed the way music is enjoyed. So, it goes both ways: the artist is creating the art in an open-ended process, and the viewer is invited to perceive the painting in an open-ended way. That is why it’s never boring talking about modern art, because everybody is going to see different things in it. Some people ask what the artist wanted to ‘tell’ us. But there is no answer to this, because even when the artist explains the work, once the art is made, it’s really open to interpretation. And also, sometimes the artists don’t know exactly what they’re doing, while they’re making the art. They don’t have a specific idea in mind.

When we look at modern art, people can have very opposite viewpoints. Looking at a Jackson Pollock painting, one person may say, ‘Oh, it looks like he was angry.’ Someone else will not see that. They may say that it looks like complete chaos. Someone else will say, ‘That looks so joyful.’ How is it that we’re looking at one object and seeing different ideas? How does that work? The art itself is ambiguous; it invites different interpretations. There’s a paradoxical element to this. There is also a life lesson in it: there are social and emotional elements that remind us not to be too focused on our own viewpoint, on the ‘I’m right’ belief. We all see things in different ways. We perceive things based on our own experience. So, we all need to take a little time to listen to somebody else, and go a little onto their side. We need to take an interest in what that person is saying. It doesn’t matter if they agree with you. Art provides a good lesson as it brings together these different perspectives into an open-ended conversation. And it teaches civility.

Today, we are often fed things that we already like. As soon as you buy something online, you’re going to be fed with similar things. You watch a film on Netflix, and you’re going to be presented with similar films. Why not try to watch a movie you don’t like? Or try to listen to somebody to understand how they think. It can be challenging. Right? Instead of saying, ‘I never want to talk to that person’, why not listen? You do not have to agree with them, but you might be able to understand them a little better. Art has these lessons, where we’re talking about open-ended interpretation.

Gil: Indeed. I always say: ‘Art will save the world’…

Joyce: Yes… I think that doctors save lives, and art gives people something to live for… Artists are just as important as surgeons…

Gil: Can inspiration itself evolve and change while artists create the art?

Joyce: Yes, absolutely. There’s a saying ‘Don’t wait for inspiration, because art is perspiration.’ Don’t wait for inspiration to fall on you because you have to just get to work. Inspiration sometimes comes in just starting to work; you can’t just sit and wait to get inspired.

Sometimes there are those moments in life where you just get inspiration. You walk and see this beautiful garden, and get inspired. But to me, that doesn’t happen too often. Usually, it takes a little discipline, where you have to get your materials and start making something, right now. So, art happens in the doing, not in the thinking about it a lot.

As you get the initial inspiration, the initial idea, you then paint that idea, and it’s going to evolve. You don’t know how it’s going to evolve. Lee Krasner said: ‘I surrender. I don’t will the painting.’ She said that she starts off, and it could be using a green painting, for example, that then would come out yellow (I don’t remember the exact colours she stated.) She doesn’t ‘will’ the painting. So, inspiration might be a spark, but then it’s going to evolve.

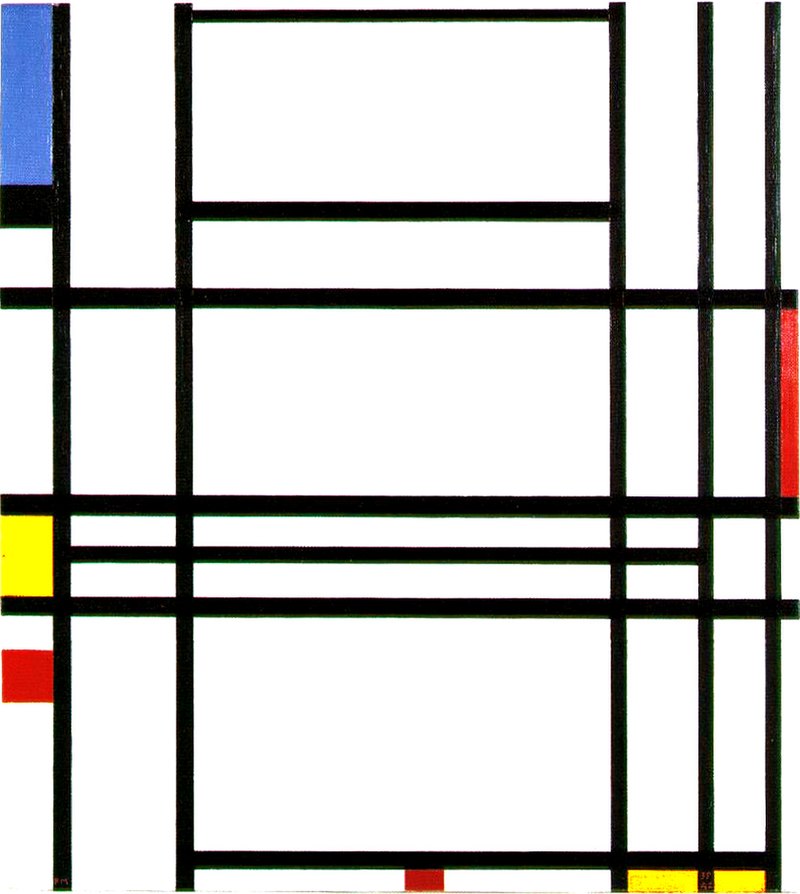

Mondrian’s range is specific. Once he starts doing grids, he stays with the grid. And Picasso was creating ceramics, murals, etchings; he constantly changed his style as well. So, different artists have different sensibilities. My sensibility personally is that I’m not interested in mastering one medium. I’m really interested in ideas. It could be in any material – it could be a painting or a sculpture. I’m interested in the ideas, and whatever material serves best those ideas.

The versatile artistic styles of Picasso. Left: ‘Sleeping Peasants’ by Pablo Picasso, 1919. Gouache, watercolour and pencil on paper, 31.1 × 48.9 cm, Museum of Modern Art. Right: ‘Girl with a Mandolin (Fanny Tellier)’ by Pablo Picasso, 1910. oil on canvas, 100.3 × 73.6 cm (39 × 28 in), Museum of Modern Art, New York. Images in public domain.

Mondrian’s style has evolved, yet he would focus on a specific style for long periods, such as this grid style work. ‘Composition No. 10’ By Piet Mondrian, 1939–1942. Oil on canvas, private collection. Image in public domain.

Gil: Let’s talk about how artists choose the tools to create their artwork.

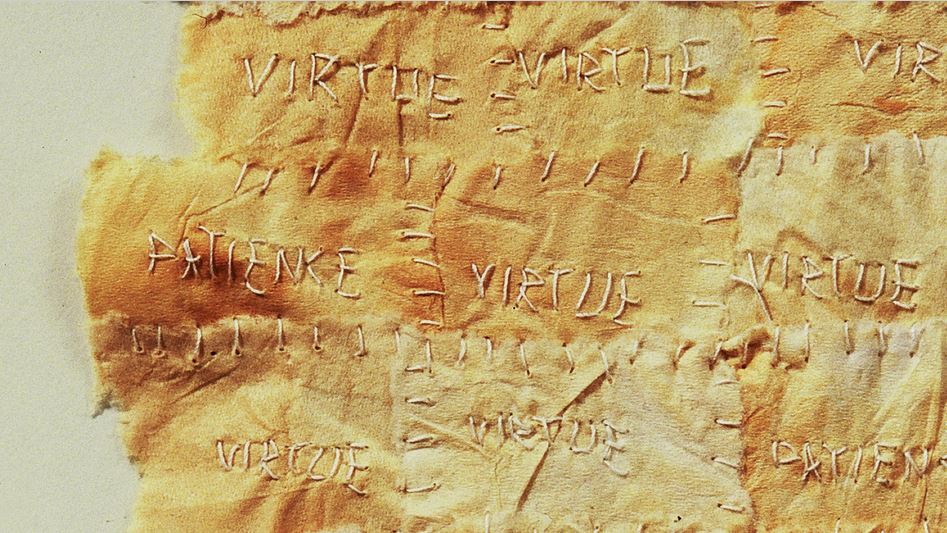

Joyce: For me, the tool has to serve the end purpose. You have to choose a tool that makes sense for what you’re trying to create. For example, I was working with the idea of fragile materials. I started to use sewing, using little tiny needles, because that served the purpose. I didn’t need glue anymore because now I’m sewing. If I’m making a painting, I want a paintbrush; that makes sense.

‘Patience-Virtue’ (detail), mixed media; tea-stained tissue, thread, by Joyce Raimondo, 1995. © The artist.

Now Pollock used unusual tools and techniques. He was using a stick or brush to drip paint instead of applying paint while touching the canvas with a paintbrush. This idea originated from a workshop that he took with David Alfaro Siqueiros, the Mexican muralist. Siqueiros held an experimental workshop in New York City. He worked with a group of artists who he recruited to use industrial techniques. This was an act of rebellion against authority and fascism. Using new techniques, not relying on the old techniques that served capitalism. He taught how to use a spray gun, how to use some dripping, how to stencil, and how to use unusual surfaces; he was opening all this up. At that time, Pollock’s work completely changed. Pollock took these ideas forward into his drip painting. Why did he use house paint? Because it’s more fluid, it drips easily. Why is he putting the canvas on the floor? It’s practical, gravity pulls the paint down, so it’s going to stay wherever it lands.

Gil: It was a new technique that Pollock learned, and he experimented with it; taking it further? How much experimentation is important in art?

Joyce: Experimentation is like play. Scientists experiment because they want to solve a problem. The experimentation can be open where you don’t even have an original hypothesis that you’re trying to solve. Watch children at play. It’s a joyful thing. A child is building with blocks, they’re playing, they’re experimenting. They knock it down, and build it again. And they’re learning how the blocks are behaving, how high they can build – they’re discovering. So, artists bring that into art; the play and experimentation, where you’ll discover a lot more… I just dripped paint and wait, what happened? Look at the way that the paint marbleized. I didn’t expect that to happen. Maybe I’ll use that technique in my entire painting. You’re going to discover new things. It’s very rich.

Gil: When dripping paint, you do not have control over it.

Joyce: Pollock actually said that he can control the flow of paint. He was controlling, and yet also intuitively improvising. When he was painting, it was intuitive yet he also mastered the technique. One might intuitively know that if you hold the stick in a certain way and move it slowly, you’re going to get one kind of mark. And if you hold it up here, and go quickly, you’re going to get a different mark. This is similar to drawing or painting with a brush. With experience, you’re going to know how it works… if I pressed that pencil really hard, you’re going to get a certain kind of mark. You become so masterful at it, that you can just let the process flow. But it’s not random. It’s not pure experimentation.

Pollock is a master at drip painting technique. So, he’s not stepping back and thinking, ‘oh, now I’m going to do this.’ Rather his work becomes very improvisational, similar to jazz musicians, who are so masterful at their instruments that they can play together and hold a structure while also being in the moment and improvising, and the result is unexpected. You wouldn’t say a jazz musician is experimenting. No. They are improvising.

Of course, there are elements of experimentation. For example, sometimes Pollock would put sand in his painting. Sometimes he adds broken glass, or would cut his paintings up, trying big format, small ones, and long, different colours. So, overall, yes, there’s an element of experimentation. But there’s also an aspect where he is a master painter.

Gil: do we know when he was in control at work, and when he was not in control? Did he ever speak about this?

Joyce: No, I’ve never heard a quote about this. But it’s more about the idea of being one, a Zen thing, being one in the moment. You’re one with the painting. So, let’s allow one mark to lead to the next one. And you’re not thinking about it, you’re not analysing it. It’s a different way of thinking. It’s intuitive. It’s pure intuition, like automatic writing. It is definitely letters and words, but you don’t define the words and you don’t define the structure.

With automatic painting or drawing, we find a range. Some artists are 100% automatic. There’s no rationale or determination. Their work is completely random. But then, other artists are not completely automatic. It’s not like you’re closing your eyes and letting the work flow. There’s a range where they are still determining the marks, but letting it flow out. Picasso and Pollock both talked about having no idea what’s going to come in, as one mark leads to the next. It’s like an adventure.

© Journal of Creativity and Inspiration.

Images copyright as specified.

Joyce Raimondo is the author of seven children’s art books, including The Museum of Modern Art’s popular ‘Art Safari’ series and the award-winning ‘Art Explorers’ books. A painter and sculptor, her illustrations have been published in the New York Times, Boston Globe, and numerous publications. Former Family Programmes Coordinator at The Museum of Modern Art in New York, she is a leading expert in museum education. She is currently the Education Coordinator at the Pollock-Krasner House and Study Centre – a national landmark in East Hampton, USA, and the Founding Director of Imagine That! Art Education. Designed to foster creative thinking, her programmes serve people of all ages and abilities worldwide.

Gil Dekel is a doctor in Art, Design and Media, specializing in processes of creativity and inspiration. He is a lecturer, visionary artist, Reiki Master/Teacher, and co-author of the ‘Energy Book’. He was awarded the Queen Elizabeth II Platinum Jubilee Coin, in recognition of his dedication and commitment to pastoral work at Hampshire Constabulary.