Vision and reality: William Blake’s mythic system

5 July 2024 – Vol 2, Issue 3.

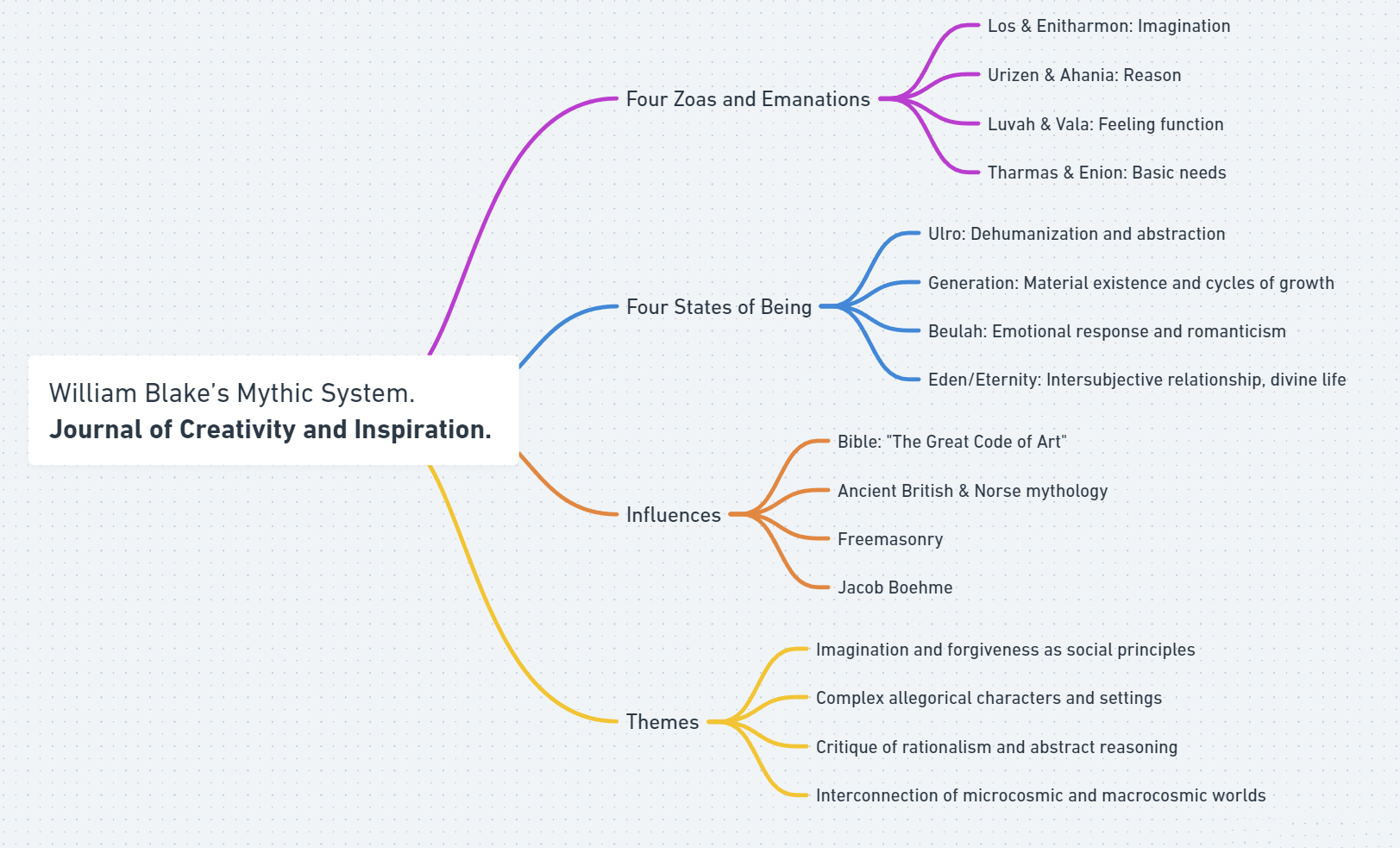

William Blake’s mythic system is designed to change the way we think and see, to lead us into a world where imagination and ferocious forgiveness are social structuring principles. Featuring Zoas, Emanations, and different states of being, Blake’s system evolved throughout his working life: between 1789 and 1820.

Blake’s Four Zoas and their corresponding Four Emanations:

| Zoas | Emanation |

| Los & Enitharmon | Imagination |

| Urizen & Ahania | Reason |

| Luvah & Vala | Feeling Function |

| Tharmas & Enion | Basic Needs |

Blake’s Four States of Being:

- Ulro

- Generation

- Beulah

- Eden/Eternity

In those 31 years, he created 13 illuminated books, and a manuscript called Vala, or the Four Zoas (FZ). He never engraved that text, but his subsequent books – Milton (1804), and Jerusalem: The Emanation of the Giant Albion (1804-21) – assume that you know about Blake’s characters and locations. Blake’s system is most fully formed in Jerusalem (J), his masterpiece, which, Blake tells us, was dictated to him by Jesus.

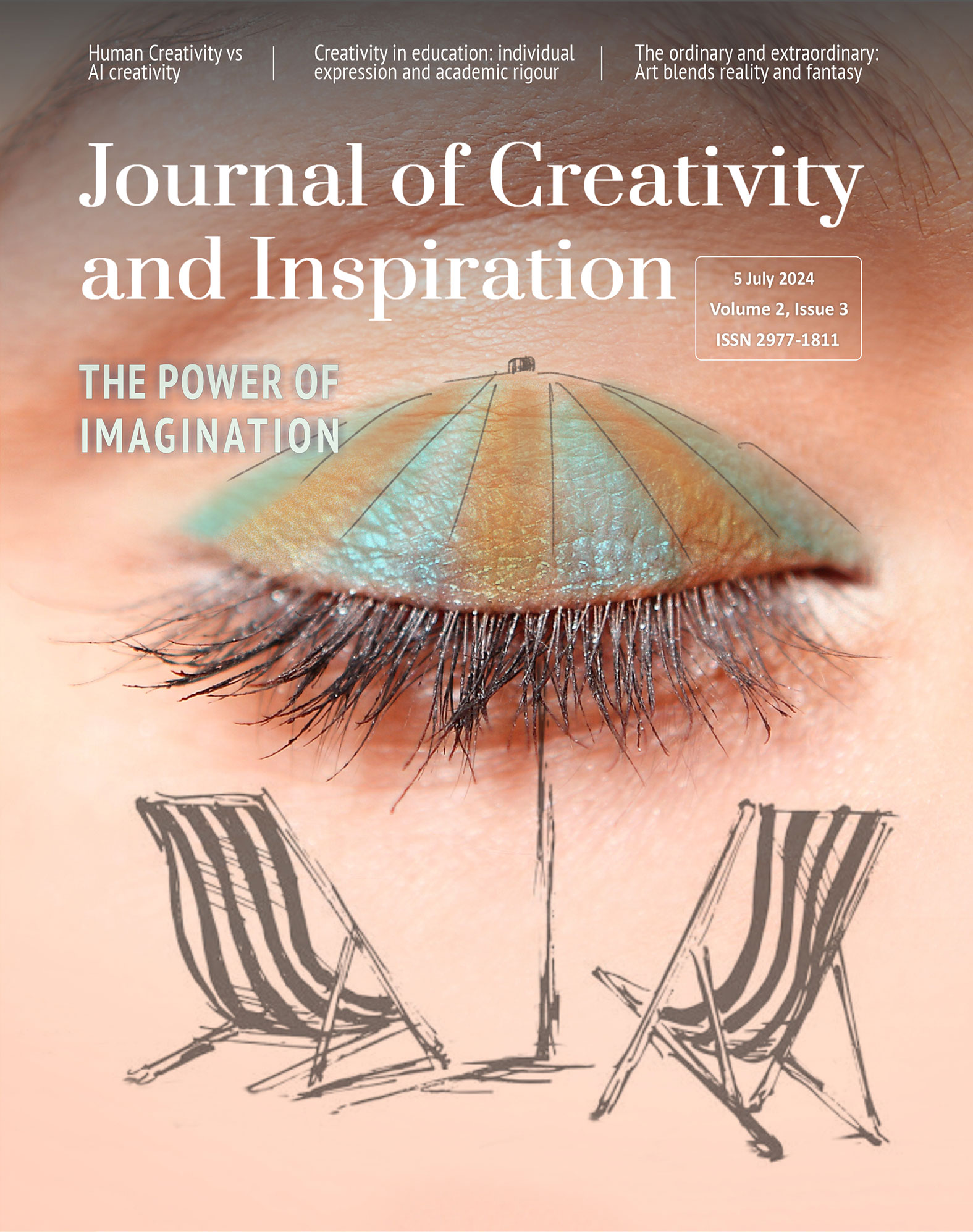

‘Jerusalem’ by William Blake (detail), Plate 9, “Condens’d his Emanations…” Part of: Collective Title: ‘Jerusalem: The Emanation of The Giant Albion’, Bentley Copy E. Date 1804 to 1820. Relief etching printed in orange ink, with watercolour and pen and black ink on moderately thick, smooth, cream wove paper. Image in the public domain, via Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1992.8.1(9).

Unfortunately, this grand poem is rarely read, because of its complexity. Packed with allusions, peopled by characters called Zoas and Emanations, it takes place not only in physical settings, but in fluid mindsets called Ulro, Generation, Beulah, and Eden/Eternity. Additionally, Jerusalem contains what Jon Mee calls a ‘bricolage’ of imagery[1], stemming from sources that shaped Blake’s consciousness. He learned to read by reading the Bible, guided by his mother, who’d been an enthusiastic member of the Moravian Fellowship before her marriage to Blake’s father.[2] Throughout his life William Blake treasured the Bible; he calls it “the Great Code of Art” (K777). He assumes that his readers know it; most of his contemporaries knew it very well.

During his seven year apprenticeship (from 1772 to 1779) young William Blake encountered ancient British (and Norse) mythology. His master, James Basire, was the official engraver to the Society of Antiquaries, a collection of scholars and learned men exploring the nature of Druids, and early British history. Many Antiquaries, like Benjamin Franklin,[3] were also Freemasons, and some believed, as Tom Paine proclaimed in his 1805 essay, “Origins of Freemasonry,” that “Masonry is the remains of the religion of the Druids.”[4] Masonic imagery and ritual were literally in young Blake’s face, for the Freemason’s Tavern and Hall was built directly opposite Basire’s studio. Blake also read the works of Jacob Boehme (among other esoteric writings). He was fourteen when he began his apprenticeship and the ideas and imagery he absorbed interweave in Jerusalem with allusions to Blake’s personal and political predicaments more than forty years later. His epic’s structure is somewhat akin to that of St. John’s Revelation, which (according to Benjamin Heath Malkin, his earliest ‘biographer’) was Blake’s favourite book.[5] A ten-year old, unencumbered by theology, might be enthralled by the imagery in John’s Apocalypse, not caring what it means. The Book of Revelation is filled with dragons and beasts, heroic angels, an emerald rainbow, glorious music, a woman clothed with the sun, an evil harlot. It’s a bit like a Marvel comic. Its structure, and layers of meaning, can’t easily be systematised.

Blake’s multifaceted epic is at least as complicated. His individual characters, his Zoas and Emanations, can take many forms. Zoas embody principal aspects of being human: Reason, Imagination, Feeling Functions, Primal Needs. Only through their unique Emanations can Zoas relate to one another, with others, and with God. All creatures and cultures depend upon Emanation, which is feminine-divine.

Ideally, Zoas and Emanations dynamically coinhere in Blake’s Albion (a man and a land): all are part of the Divine Body, Jesus, who is both human and cosmic. Jerusalem, the sensuous Bride of Jesus, a woman and a city, is Albion’s Emanation. (Repressing and dishonouring Jerusalem, as Albion stupidly does, sparks social, spiritual, and ecological disaster.)

Emanations and Zoas are not flat allegorical figures. Like us, they have motivations, domestic squabbles, strong emotions. They can be fallible and they can change. They’re elemental as well, like Ariel in Shakespeare’s Tempest. Emanations and Zoas exist not only in the world of the text; they also dwell microcosmically within us, and macrosomically, they shape nations, politics, cultural values. When creatively interconnected, internally and externally, we and our nations can participate in divine life. Opening inward eyes can affect the whole body politic.

In Blake’s Divine Body, in the state of Eden/Eternity, the Zoa called Urizen embodies reason and clarity, wielding the great golden compasses emblematic in Freemasonry. Los, a cosmic blacksmith, forges prophetic vision with the help of a huge hammer like Thor in the Norse mythology, a figure Blake encountered during his apprenticeship. Los is akin to Blake himself, first appearing in The Book of Urizen (1794), followed by two books of his own: The Book of Los (1795), The Song of Los (1795). His character deepens, develops, and changes throughout Blake’s life.

‘Jerusalem’ by William Blake (detail), Plate 73, “Such are Cathedron’s golden Halls…” Part of: Collective Title: ‘Jerusalem: The Emanation of The Giant Albion’, Bentley Copy E. Date 1804 to 1820. Relief etching printed in orange ink, with watercolour and pen and black ink on moderately thick, smooth, cream wove paper. Image in the public domain, via Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1992.8.1(73).

Luvah and Tharmas don’t have books of their own, but Luvah, the Zoa of love and emotion (including political passions) makes his appearance in Blake’s work earlier than the others, in The Book of Thel (1789). He features prominently in The Four Zoas (1795-1804), appearing every Night (or episode). The Four Zoas begins with Tharmas, “the parent sense, the tongue” (FZ1.24 K264), who has to do with basic physical life: primal seas, hunting and loving .

Zoas are almost always masculine characters and each masculine Zoa has a feminine emanation. In Eden/Eternity Zoas and Emanations joyfully commingle – spiritually and sensually.

Ahania, Urizen’s feminine counterpart, has a book of her own. She loves Urizen very much, and can be seen as a gracious organiser.

Enion who conjoins with Tharmas, is something like an earth mother. Throughout The Four Zoas she has terrible domestic trouble for she seeks dominion over Tharmas, which nearly destroys their love.

Enitharmon, the Emanation of Los, contends with love and jealousy in Jerusalem as well as in The Four Zoas. She’s referred to as “the wife of Los” in mundane time; most scholars agree that she’s a bit like Blake’s wife, Catherine, who helped print and colour his books.

In the Book of Urizen (1794), Enitharmon and Los have a child named Orc, a fiery creature filled with revolutionary energy – who can promote life, liberty, and happiness, as well as the slaughter of thousands by the guillotine. He’s a pivotal character in Blake’s political prophecies, Europe and America (1795). But he makes only a cameo appearance in Jerusalem.

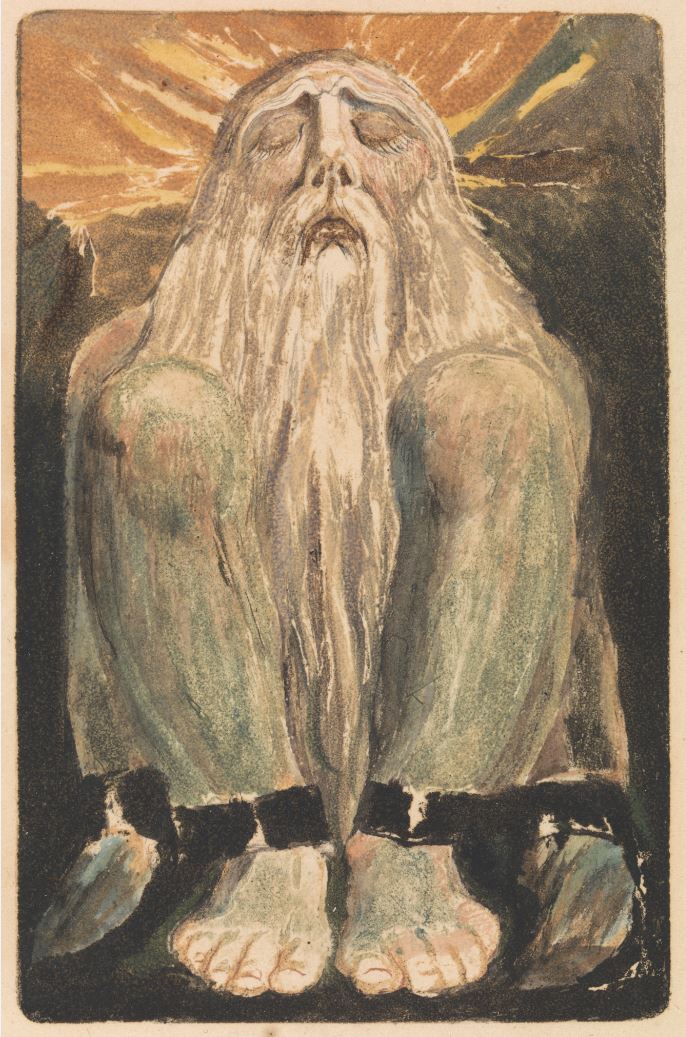

There Orc’s furious destructive energy emanates from Vala, the Emanation of Luvah. When Jerusalem, feminine-divine, is banished, Vala’s consort gets sealed in a furnace. Vala can no longer commingle with him. Then she, who co-creates with Jerusalem in Eternity, becomes shadowy, ferocious, jealous, and destructive. Repressed erotic energy spawns violence and war.

War, poverty, and repression do not exist when Jerusalem rises, and we enter the state of being Blake calls Eden/Eternity.

‘Jerusalem’ by William Blake (detail), Plate 92, “What do I see!…” Part of: Collective Title: ‘Jerusalem: The Emanation of The Giant Albion’, Bentley Copy E. Date 1804 to 1820. Relief etching printed in orange ink, with watercolour and pen and black ink on moderately thick, smooth, cream wove paper. Image in the public domain, via Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1992.8.1(92).

Now let us consider the four states of being in Blake’s mythic system: Ulro, Generation, Beulah, and Eden/Eternity. Think of these four states in terms of a tree. Imagine a pine tree: it can exist in Ulro, Generation, Beulah, and Eden/Eternity. In Ulro the tree isn’t an individual tree: it’s an abstraction. A paper company can put our tree in Ulro; the company sees it as a statistic, a tiny factor in cost-benefit analysis (as dead children become “collateral damage” in a Pentagon report). Ulro makes it possible for us to dehumanise people and nature.

We might not be empathic in the state called Generation, either, but Generation does take into account cycles of growth, life, and change. When our tree is “harvested” by the paper company another is planted; this is good business. The beauty of our tree isn’t important; it’s alive, but only in what Blake would call a “vegetative” or material way. In Beulah, however, we have an emotional response to our tree.

In Beulah’s romantic state of being we may rest beneath the tree, enjoy its beauty, write a poem about it. We might hug the tree or embrace our beloved beneath it. If blighted by Selfhood we can treat the beloved (and the tree) as an object and fall into emotional and spiritual Ulro. When freed from Selfhood then we and the tree and our beloved participate in the Divine Body, the Saviour’s Kingdom: Eden/Eternity.

In Eden/Eternity, you and I and the tree are in an intersubjective relationship. We see the tree and the tree sees us. We interconnect. This does not negate the values of other states of being. In Eden/Eternity we retain the differentiations of Ulro, the productivity of Generation, and the bliss of Beulah. Eden/Eternity is a fourfold state of being. Our tree is a tree of life – and so am I, and so are you.

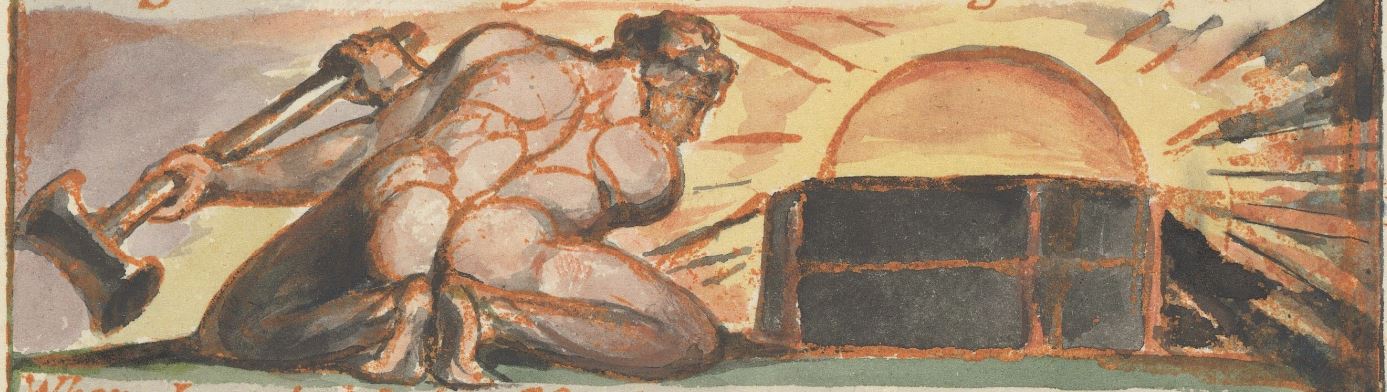

In Blake’s Divine Body we can eat from the tree of life. But Selfhood prevents that from happening. In The Book of Urizen, we see the prototype of Albion, trapped in Selfhood, in Ulro’s “mind-forg’d manacles.”

‘The First Book of Urizen’, by William Blake, Plate 12 (Bentley 22). Part of: Collective Title: ‘The First Book of Urizen’, Bentley Copy C. 1794. Colour-printed relief etching in orange-brown ink, with watercolour on moderately thick, slightly textured, cream wove paper. Image in the public domain, via Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1978.43.1431.

William Blake gleaned the term ‘Selfhood’ from Jacob Boehme, a seventeenth century Lutheran visionary – and alchemist. In Blake and Boehme, “Selfhood” is like a disease. In Blake’s system there is no “true Self,” as in the writings of Carl Jung (who was also influenced by Boehme). Blake’s Selfhood creates destructive conflict; Selfhood impedes forgiveness and interconnection. It dehumanises others, craving power and control. It’s equated with Satan (J27) and a creature called the Spectre (J33.17–18, J58.46-9, K659), “the abstract objecting power that negatives every thing” (J10.14, K629). Selfhood does not “emanate”, or give forth “fibres of love.” It traps us in Ulro, closing our minds, destroying the dynamic balance between the Four Zoas within us and in our culture. Selfhood animates what Blake calls “the Spectre,” wreaking havoc in The Four Zoas, Milton, and Jerusalem.

As all people contain some cancer cells, so does every person and nation have a Spectre, which can, when empowered, be deadly. A Spectre can encourage you or your culture to be violent, unjust, unproductive: it can make you think your work is no good; it can trap you in anger, envy, or fear. Pulverizing Spectres requires determination, courage, divine help – and vision. Imagination and vision are a spiritual immune system which Blake seeks to bolster.

‘Jerusalem’ by William Blake (detail), Plate 6, “His Spectre driv’n…” Part of: Collective Title: ‘Jerusalem: The Emanation of The Giant Albion’, Bentley Copy E. Date 1804 to 1820. Relief etching printed in orange ink, with watercolour and pen and black ink on moderately thick, smooth, cream wove paper. Image in the public domain, via Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1992.8.1(6).

Emanations, Zoas, and human beings also have Shadows. Jerusalem, the Emanation of the Giant Albion, must contend with Vala, who becomes Shadowy when Albion negates the Saviour and banishes the feminine, but Vala is not a Spectre. The Spectre must be pulverised; shadows must be transformed. When Los shatters his Spectre, Vala can be incorporated in Jerusalem again, imbued with divine life. Unfortunately, Blake does not tell us how to tell the difference between Spectres and Shadows. He does show, however, that the “Druid Spectre” is annihilated before all things coinhere in Eden/Eternity.

Many readers are puzzled by Blake’s Druids. They’re denizens of Ulro. In Jerusalem, Albion is “the parent of the Druids” (J27, K649), and his bellicose sons and daughters wreak havoc among the rocks of the Druids. Blake’s bloodthirsty Druids in Blake are addicted to abstract reasoning.

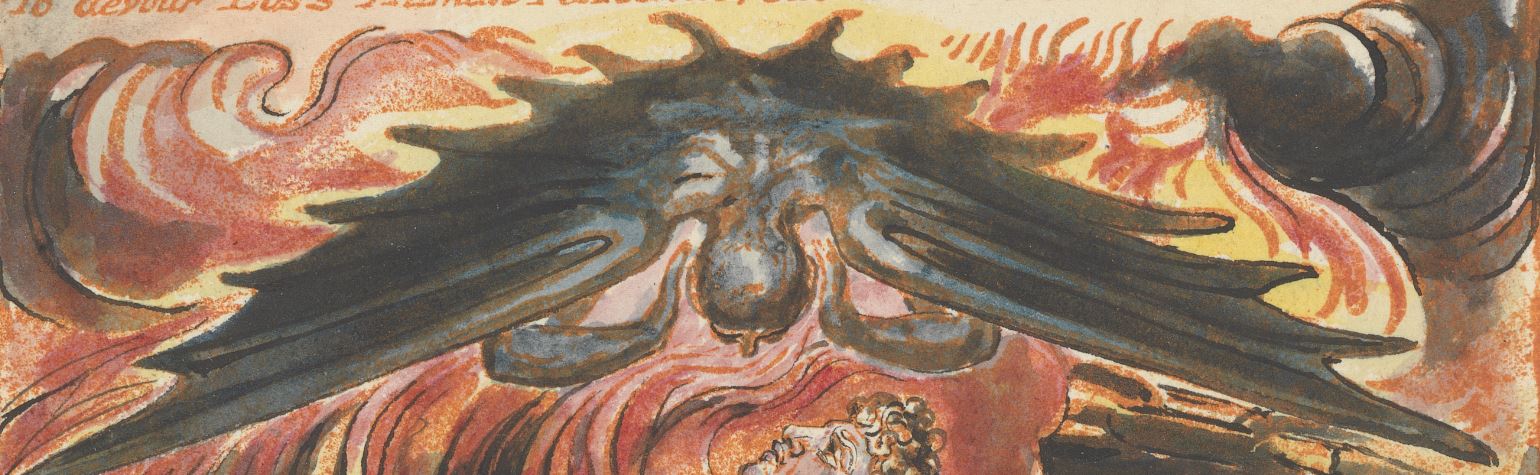

‘Jerusalem’ by William Blake (detail), Plate 69, “Then all the Males…” Part of: Collective Title: ‘Jerusalem: The Emanation of The Giant Albion’, Bentley Copy E. Date 1804 to 1820. Relief etching printed in orange ink, with watercolour and pen and black ink on moderately thick, smooth, cream wove paper. Image in the public domain, via Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1992.8.1(69).

Blake encountered bloodthirsty Druids in the first year of his apprenticeship, helping his master, James Basire, with engravings of (so-called) Druid stones and hammer heads for volume II of Archaeologia (A), the journal of the Society of Antiquaries which appeared in 1773. The text accompanying those engravings likens ‘antient’ pillars in the churchyard at Penrith to the ruins of Druid temples; the author, Mr. Lyttleton, wonders whether British or Norse Druids constructed those temples (A1773: 50-2).

Like many learned Antiquaries, William Blake can conflate British Druids with Norse warriors, harbingers of death and destruction. Caesar’s Commentaries describe Druids burning victims in their Wicker Man,[6], and Wordsworth alludes to this in his “Salisbury Plain” poems (48, 1794), recalling the suffering of those burnt alive in the Druid’s “giant wicker.”[7] Blake places his “Wicker Man of Scandinavia” among “Druid Dragon Temples” in Jerusalem (J47:7 K677). In those Dragon Temples “the abstract reasoning power” is worshipped, dehumanising people and nature, inciting violence.

Some Antiquaries championed Druids as paragons of rationality and reason, idealising their culture. (Thomas Paine, author of The Age of Reason[8] did so, too.) But Blake despised the worship of reason at the expense of imagination and feeling. Reason is necessary – but imagination, in Blake, is paramount. As he engraved for Basire he’d have been very aware that thousands of men in white leather aprons, dedicated to God the Geometer, the Great Architect of the Universe, were building temples of Jerusalem in their rituals, not only in the Masonic Hall across street, but in lodges throughout England’s green and pleasant land, bearing banners emblazoned with golden compasses, like those which Blake gives). Blake was certainly intrigued by their worldwide building of Jerusalem – but his Jerusalem, a woman and a city, could never be dedicated to what Freemasons call “sceptered Reason.”

‘The Ancient of Days’, frontispiece to Europe a Prophecy, by William Blake. Cpy K, in the collection of the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge. Image in the public domain via Wikipedia.org.

Freemasonry is almost wholly masculine[9] but in Blake’s masterpiece, Jerusalem the feminine divine, permeates and enhances the identity of every living thing: “even tree metal earth and stone” (J99:2). There are no secret words, no spiritual engineering principle reserved for the elite, no hierarchy or great chain of being with God at the top and rocks at the bottom. In Blake’s mythic system even trees, metal, earth and stone are integral to life in the Divine Body. The smallest sprout can have cosmic resonance. Inner worlds and outer worlds coinhere.

Blake’s understanding of the coinherence of inward microcosmic and outward macrocosmic worlds may derive from reading Boehme’s Aurora. There he encountered a micro- and macrosmic sevenfold fire world; in which wrath and love, fire and light, contend. Did Boehme’s sevenfold fires inspire the seven furnaces of beryl in Jerusalem – where Los with his hammer contends with wrath and love, until at last they meld, reintegrating all Zoas in the furious joy that transforms souls and societies? Love and wrath are what Blake would call “contraries” and their energy can be powerful, as we see in Blake’s Marriage of Heaven and Hell (c.1791, K148). Love and wrath can transform societies and souls – in what Blake calls, “Wars of Love.”

Spiritual and social transformation, Blake knew, requires ferocious forgiveness. Strength and compassion coinhere when Emanations flourish, connecting all Four Zoas within each human soul and every nation. When Emanations and Zoas interrelate all created things, are in Eden/Eternity, human-divine. Differences are celebrated; judgement is forgiveness. A culture of peace on earth is possible.

Notes:

[1] Much of Blake’s work can be called a ‘bricologe’. Mee discusses this in his fine book, Dangerous Enthusiasm (Clarendon Press, Oxford, 2002).

[2] The Moravian Fellowship, led by a visionary Lutheran pastor, was known for its mission work and marvellous music. Members lived communally, and all that they did – farming, painting, cooking, composing – was meant to be prayer and praise. Lovemaking between a husband and wife was the highest form of prayer and praise. See Craig Atwood, ‘Sleeping in the Arms of Christ: Sanctifying Sexuality in the Eighteenth Century Moravian Church’ (1997). Journal of the History of Sexuality. 8.1, 25-51.

[3] Benjamin Franklin joined the Society of Antiquaries on 13 May 1773. See A List of the Members of the Society of Antiquaries, London: 1798, p. 26.

[4] Paine, Thomas (1805) ‘Origin of Freemasonry’. In Philip S Foner (ed.), The Complete Writings of Thomas Paine.

[5] See G.E. Bentley, Blake Records (2004). Yale University Press, 567.

[6] S. Foster Damon, Blake Dictionary, Brown University Press, 1965, 447, citing Caesar’s Commentaries, vi., 16.

[7] http://oldsite.english.ucsb.edu/faculty/ayliu/research/around-1800/FR/salisbury-plain.html

[8] Paine’s Age of Reason was published in three parts, between 1794 and 1807. Blake knew Paine.

[9] Only in France was and is there a lodge that admits women.

At a glance

© Journal of Creativity and Inspiration.

Images in the public domain.

Susanne Sklar has taught Blake’s poetry, painting, and prophecy in Russia, China, Sweden, the USA, and the UK (at Oxford). She’s written several articles and a book, Blake’s ‘Jerusalem’ As Visionary Theatre (OUP). She’s been a peace researcher and activist, working in the Holy Land, and in Russia/Soviet Union. Additionally, she’s been an actress and a social worker.