Creativity in education: individual expression and academic rigour

5 July 2024 – Vol 2, Issue 3.

The journey to meaningful teaching is not merely a pedagogical challenge but a creative endeavour. The cornerstone of promoting creativity in teaching lies in the design and execution of courses that encourage imaginative thinking and problem-solving. This article will focus on using words and images as tools to express inner knowledge in the process of developing academic thinking.

‘The power of imaginative thinking’ by AI / Gil Dekel. 2024.

The method ‘Academic Thinking Processing’ (Marbach, 2001) is designed to assist students in structuring their PhD theses by prioritizing intuitive knowledge before consulting existing literature. This approach begins with the student deciding on a topic based on personal interest and prior knowledge, without initial reference to external sources. In that way, the topic is intrinsic and authentic to the student. The student then defines the topic, outlines the need, and proposes criteria for examination (three keywords) – using their own ideas, thoughts and associations, without consulting the literature at this stage. These steps culminate in a preliminary hypothesis rooted in the student’s own insights. Then the student carries out a literature search to support and refine their ideas, balancing individual creativity with academic rigour.

The student can work individually, and also in a group, as a learner can actively build knowledge by their own through the interaction with the environment (“Piaget’s individual constructivism”) (see; Piaget, 1963; Piaget and Inhelder, 1977; Lavi, 1993; Druyan, 1999; Sebastian, 2005).

Inspired by Piaget, I have been teaching students in courses where they have engaged in self-learning within small teams. Teams of two to three members performed joint research tasks, drawing on their collective capabilities, using words and images in the process.

Words

In one course, Israeli students from a graphics department were tasked with exploring the theme ‘Mother’s Love’. They were asked to define the theme in 3 keywords. Initially, they struggled in this task, coming up with the following aspects (keywords) that overlap and that led to conceptual duplication:

- love,

- emotion,

- warmth.

The word ‘love’ is already present in the name of the work, ‘Mother’s Love’. Hence, there is a duplication. At first, the students did not feel there was any issue with that. To help them I brought several examples from their field of expertise (graphic design). One example was asking them to explore this theme: ‘The influence of the drawing tool on the style of the artwork’, which the students divided into three aspects:

- drawing tool,

- paper,

- pencil.

They then noted that a ‘drawing tool’ cannot be an aspect (keyword), because the entire topic concerns drawing tools, and each aspect should represent one point of view out of the whole. With this, they suggested the following aspects:

- pencil,

- charcoal,

- paper.

These three aspects are suitable since they do not overlap. Each aspect represents a unique part of the whole. As the students now understood that each aspect must be a unique part, I asked them if they could distinguish between love, emotion and warmth. After several attempts, they raised the possibility that the three aspects were too close to each other and even overlap, and were likely to create conceptual duplications. In other words, love is one type of emotion, so these two words overlap.

Images

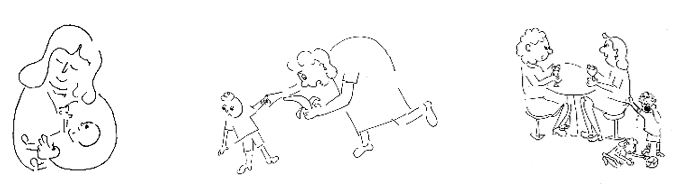

One of the team members said she had an idea of how to divide the subject into three aspects. She asked to express them through drawings:

Illustrations © the artist. Used with permission.

The resulting illustrations sparked discussions among all teams, aiming to propose a name for each of the three illustrations. Initially, the proposals were very concrete, such as ‘Feeding’, ‘Banana Stabber’, and ‘Didn’t Notice’. Gradually the team progressed towards more abstract and conceptual generalisations, which do not represent just a ‘specific case’ but a phenomenon. Eventually, we arrived at these three aspects:

- support,

- dominance,

- rejection.

These keywords are suitable since they do not overlap.

The visual exercise not only clarified the team’s understanding but also inspired their peers to think more creatively.

In another session, graphics students shared a project with paintings on the subject of ‘Rainy Day’. During the discussion, a photography student asked if there was room to give a sense of a rainy day even without using raindrops. Another student suggested looking at the painting ‘Paris Street; Rainy Day’ by Gustave Caillebotte. In the painting, we do not see raindrops, but rather alternative visual cues such as a wet street with shiny cobblestones, reflections, a greyish sky, and people wearing coats and holding umbrellas – all illustrate a rainy day without showing raindrops.

‘Paris Street; Rainy Day’ by Gustave Caillebotte, 1877. Oil on canvas, 212.2 × 276.2 cm. Image in public domain.

The group consisted of students from four departments: Graphics, Fashion, Photography and Architecture. The gathering of teams from several different fields of knowledge invited inter-disciplinary contributions: discussion on the idea of ‘using light and shadow’ among the members of the photography team, the ‘adaptation of building materials’ among the members of the architecture team, and the ‘textures on an inspiration board’ among the members of the fashion team.

The use of words and images in the process of developing original thinking helped students articulate their insights and foster deeper understanding. Creating a climate of growth involves encouraging students to take ownership of their learning and their ideas, views, and biases. This helps them see challenges as opportunities for growth rather than obstacles. A humanistic and constructivist framework fosters responsibility, collaboration, and respect among learners, aiming to create a transformative educational experience.

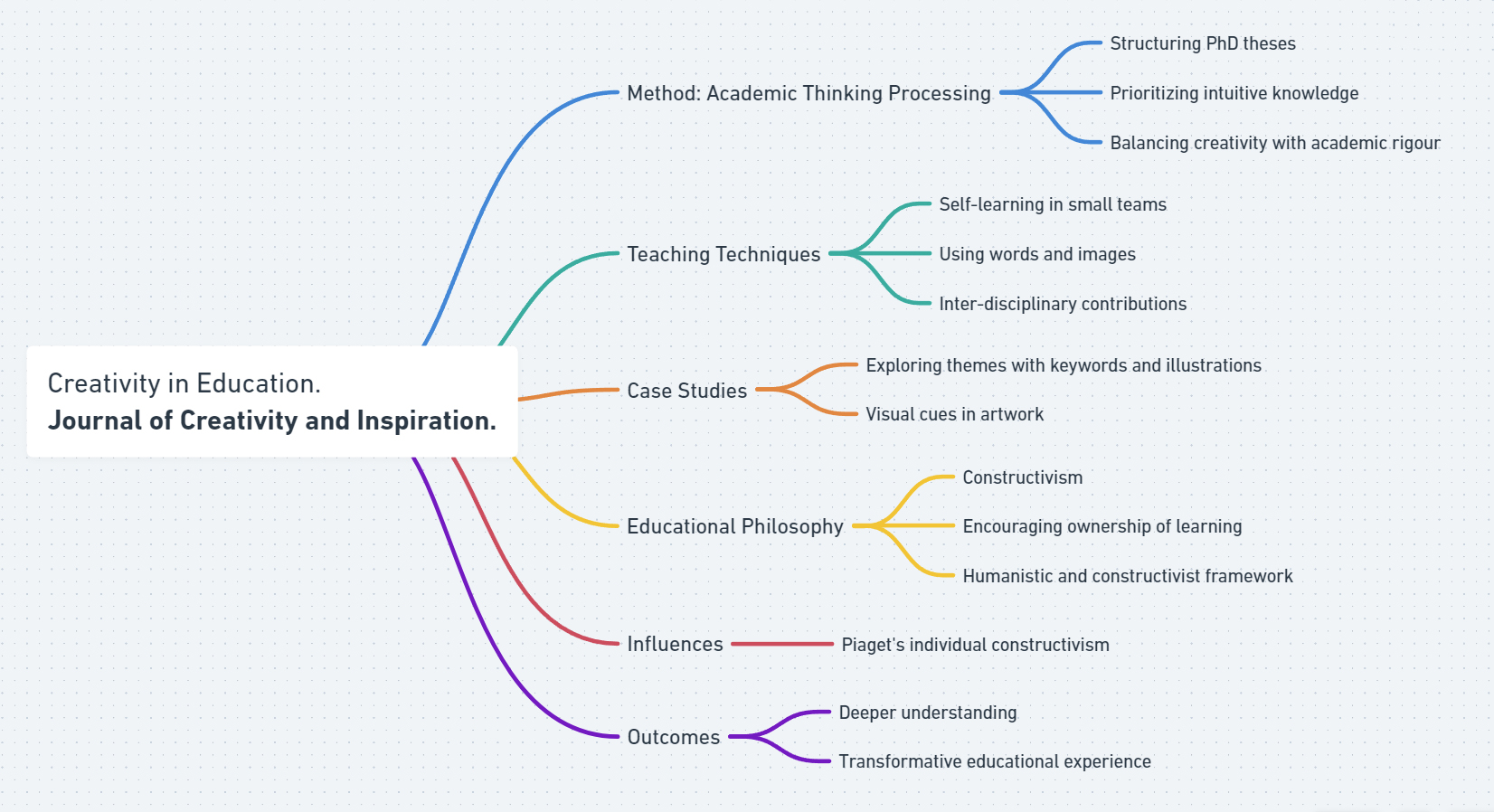

At a glance:

© Journal of Creativity and Inspiration.

Images/arts © the artists.

Dr. Amikam Marbach is an expert in the processes of developing academic thinking and creative teaching. Author of three books and numerous academic articles, he teaches innovative methods that inspire students to develop intuitive knowledge backed up by academic literature.

References

Druyan, S. (1999) Evolutionary Principles of thinking development. Tel Aviv: Ramot.

Lavi, Z. (1993) Individual constructivism, social constructivism, and education: Piaget and Vygotsky on the role of education in the development of the child. Communal Education, 56 (148-149): 78-92.

Marbach, A. (2001) Academic thinking processing. Tel Aviv: Mofet Institute.

Piaget, J. (1963) The origins of the intelligence in children. New York: Norton.

Piaget, J. and Inhelder, B. (1977) The psychology of the child. London: Routledge and Kegan.

Sebastian, E. (2005) Schemes and practices: Piaget’s terms of knowledge adaptation. Associated Contents. Available from: http://www.associatedcontent.com/article/13527/schemes_and_practices_piagets_terms_pg2