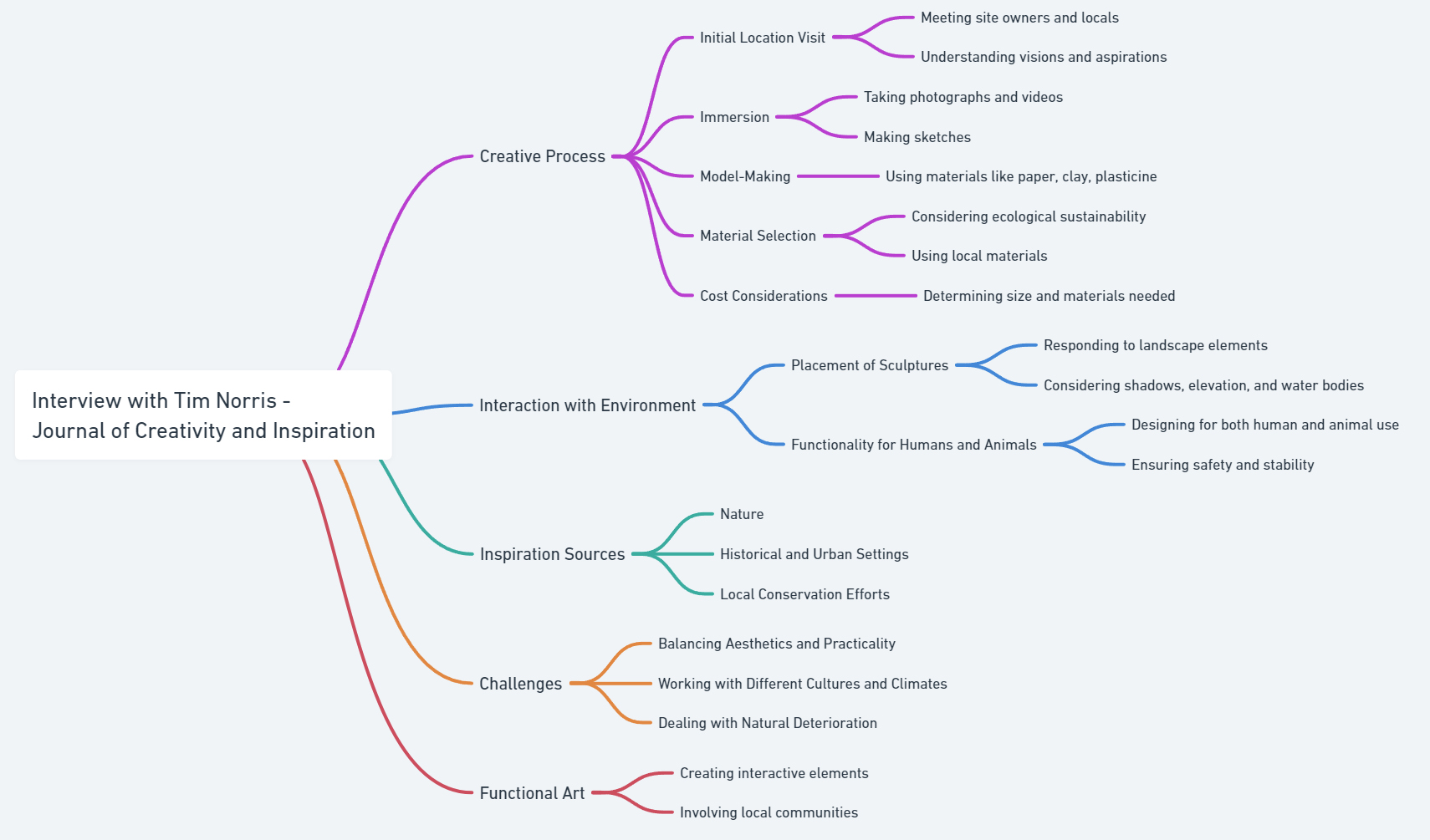

Sculpted by nature: Tim Norris interviewed by Gil Dekel

5 July 2024 – Vol 2, Issue 3.

Gil Dekel: What is the process of creating your large-scale sculptures?

Tim Norris: I start by visiting the project’s location. I meet with those involved directly with the site, whether it’s the site owner or any other individuals who live in the area. This initial interaction is crucial as I try to understand their visions and aspirations for the project.

Tim working on ‘The Journey’, red oak bark, golden rod, birch, sphagnum moss and steel. Approx size: 2.5 x 2.5 x 2.5 metres. I Park, Connecticut, USA. 2013.

I immerse myself in the location, taking photographs, videos, and making sketches – sometimes without a clear direction. The process is often shrouded in mystery initially. Sometimes, discussions with the stakeholders illuminate unexpected details about the location that may inspire a particular direction, or it could be the physical characteristics of the space or abundant materials that guide the creative process.

Following this, I often engage in model-making. This might involve using simple materials like paper, which is cheap, easy, and quick to manipulate, or other media like clay or plasticine. The models help visualise the final piece, allowing me to sketch out more detailed plans.

‘Endless flow’, mountain palm and steel. 2.6 x 2.6 metres. Taitung, Taiwan. 2022.

I also consider cost implications, which determine how big the piece will be, how many surface meters of material will be needed, and what materials would be most appropriate. Choosing materials is an exciting part of the process, as I aim to determine whether the materials should be ecologically sustainable or if there are local conservation efforts I should collaborate with.

For example, my studio is located in Wimbledon Common, in London. It is maintained somewhat as it was a century ago. Volunteers help maintain the open spaces by removing small saplings, mimicking the way herd animals would have naturally maintained the landscape. These efforts provide a rich source of materials like hazel branches, which are incredibly flexible and perfect for creating curved shapes in my sculptures. The Common also offers a blend of historical and natural inspiration, particularly with the historic trees that are centuries old near my studio. Despite London’s urban setting, it has many valued green spaces which provide essential relief and inspiration.

Gil: How do you decide where to place your sculptures?

Tim: The placement of the sculptures is connected to the surrounding elements, like large trees, bodies of water, or the elevation differences within the landscape. Sometimes, I’m working on a commission where clients ask for a piece in a specific location. At other times, I’m given more freedom, so I can explore and find a spot that resonates with me. In both scenarios, I respond to the physical aspects of the landscape: the terrain, colours, light, and where the sun rises and sets (creating shadows).

Ultimately, my creative process is a blend of technical planning and spontaneous artistic inspiration, drawing heavily from the environment and the community’s needs.

Gil: Do you incorporate sounds, such as sounds of animals, leaves, water?

Tim: I never have, although I’ve thought about using sound to enhance communication through my sculptures. Beyond just viewing the sculpture, you could also hear something. I explored this concept with a proposal for Chelsea Flower Show with the Garden Designer Rob Hardy. On this occasion, we didn’t make the final selection but watch this space…

Gil: Are your sculptures designed exclusively for human use, or are they also meant to be used by the animals living in the area?

Tim: The sculptures are for the animals too. It’s their territory as well as ours… Whether the animals appreciate the artistic value of the sculptures, I’m not sure… but there is lots of potential for them to use my works as habitat and perching. For example, ‘The Journey’ was located on a small mound in a Connecticut woodland. The sculpture is a perfect space that probably now hosts a variety of wildlife. The materials used were all native to the area and gathered from the local landscape, like red oak bark, which can support hundreds of insect species. The birds or small mammals might use the internal space for nesting.

‘The Journey’, red oak bark, golden rod, birch, sphagnum moss and steel. Approx size: 2.5 x2.5 x 2.5 metres. I Park, Connecticut, USA. 2013.

Gil: You are using natural materials, but also recycled.

Tim: Yes. Many of my pieces are located in public spaces, so I have to think beyond just the visual aspects. It’s crucial to consider the safety of children and families who might interact with these sculptures. As they’re made from natural materials that will eventually break down, there’s a real concern about stability – imagine if someone climbed on a sculpture and it collapsed. Therefore, I often integrate a structure made of steel or other durable materials. These provide the necessary strength. Steel is regularly recycled – it is possible to buy reinforcement bars that are made exclusively from UK recycled metal. It is easy to repurpose old steel components in a new way. Sometimes a recycled element can inspire a new idea…

Gil: So, there is a tension between aesthetics and practical aspects?

Tim: Yes, definitely. This is a significant struggle for me. Balancing aesthetics and practicality can sometimes feel like opposing forces. For example, making a base/foundation design that will satisfy a structural engineer, look beautiful, be made sustainably and can be easily removed and recycled when the work is de-commissioned.

Gil: How do you identify your profession?

Tim: I identify primarily as a sculptor because that is where my formal training lies. I view everything through a sculptural lens, though I am always eager to explore and push the boundaries of what defines sculpture. My work does challenge these boundaries. Questions arise about my works: are these works merely furniture-making, forestry, gardening, art, or architecture? These explorations into the boundaries of sculpture make the artistic process exciting for me.

Gil: Have you considered breaking the boundaries of the use of materials, and perhaps using living materials or connecting your sculptures to living trees?

Tim: Absolutely. I find that concept incredibly exciting and have experimented with it many times. I was first inspired by David Nash, who has been developing an ash living dome for over 40 years. Inspired by this, around the year 2000, I began a living sculpture in Somerset, growing willow trees around a steel frame. Eventually, it became quite established and strong enough to bear my weight. It needed annual maintenance to manage the growth. Unfortunately, I lost access to this land after 15 years as it changed ownership and access was no longer practical. It may continue to grow, but without my annual maintenance and guiding hand, it will eventually try to revert to its natural form.

My first ever commissioned work while still a student integrated a sculptural seat into a living tree in 1994.

Coppice Seat, Stour Valley Arts, Kings Wood, Kent.

This work lasted about 10 years. It was part of a forest managed on a rotational cutting schedule. Unfortunately, the foresters weren’t informed that it was an artwork, so when the area was due for cutting, they almost cut the tree down completely. They realized last minute that something was different and adjusted their cut, but the sculpture was still significantly altered so much so that I felt it was not my artwork anymore.

Additionally, living sculptures face challenges from wildlife too – deer and cows are particularly fond of fresh willow shoots. These animals sometimes damage the sculptures, leading to unexpected maintenance and repairs. The somerset work only really took off once I created a boundary fence around the sculpture until the trees grew big enough to fend for themselves.

Gil: Your art is functional, as people interact with it. How does this affect your decisions?

Tim: I am considering how people will interact with the sculpture. Whether it’s a bench in a park or a sculptural installation in a public space, I need to think about the user’s experience from every angle – how they approach it, engage with it, and possibly even integrate it into their daily lives.

I enjoy creating art that incorporates functional interactive elements. This helps draw people into my pieces more effectively than traditional, static sculptures might. It’s incredibly rewarding to create works that people can physically engage with, enhancing their connection to the art.

Many of my works are strategically placed to maximize scenic views, like those I created in South Wales situated on a hilltop with stunning forest vistas. Visitors can ascend the sculpture via integrated stairs, touch the materials, and feel connected to both the art and the landscape.

‘Harlech Bench’, Welsh oak, mixed local field stone. Approx size: 4 x 5 x 3 metres. Harlech, Snowdonia National Park, Wales, UK. 2003.

I prefer using materials like wood, for sculptures that are in contact with the human. Wood is warm and inviting to the touch, unlike stone or metal, which can feel cold and hard.

Gil: The piece ‘Harlech Bench’ is so beautiful, and also functional. It also integrates well with the surroundings.

Tim: The work is located in the mountains of Snowdonia – a very historic area with a castle. It was created as part of the cycle path network being developed throughout Wales. The project aimed to provide resting spots where cyclists could stop, sit, and perhaps park their bikes. In sourcing materials, I reached out to local stonemasons and foresters to find elements that represented the local area. A stonemason mentioned he was taking down a wall and had this unique glacial moraine stone, rounded by glaciers, distinct from the sharp, jagged stones typically quarried. This same type of stone was also used in the nearby castle, which added a nice touch of authenticity and connection. Additionally, we used wind-blown oak from within a mile of the site. The sawmill, mounted on the back of a truck, allowed us to process the tree right there, which not only kept the materials sustainable and relevant but also involved the local economy. This community involvement helps the artwork gain acceptance and become something of the people, not just ‘Tim’s sculpture’. Local volunteers often help with the physical work involved. It can help embed the piece within its space and community.

There are many micro-decisions involved in the process, especially when commissions require precise specifications like exact heights and thicknesses. I try to keep these details as vague as possible for as long as I can, which allows me to respond more authentically to the actual materials and the site specifics. This process of continual decision-making and testing different options helps me to stay aligned with my instinctive choices, but I always keep the end user in mind. Ultimately, my role isn’t just about crafting an impressive sculpture; it’s about creating works that integrate with their environment and fulfil the needs of my clients.

Gil: Your sculptures would change and age over the years, being outside, and exposed to the elements.

Tim: Yes, and I’m always learning from how the works age and how they deteriorate over time. Initially, my sculptures were made entirely from natural materials and were designed to be transient; if they fell down, it was part of the process. It’s bittersweet. I like to appreciate how nature would reclaim them, but it’s also sad when they’re gone.

Gil: You have been working in a few countries, with different cultural customs and climates. This must alter your work process.

Tim: Yes, the materials and also work process vary in different climates and cultures. In Taiwan, the local workers would sleep in the middle of the day due to the heat, a habit I was not accustomed to and had to adapt to. I often use local support because the projects are physically demanding and require knowledge of local resources for my materials, workspace and tools.

‘Habitat’ was created in Germany. I realised that I was quite unfamiliar with the local materials and species available. In that specific forest, birch trees are considered a weed, cut down to allow the more valuable oaks to thrive. As I explored, I noticed little specks of silvery white birch bark scattered under the bracken, which the foresters had cut down. This discovery was pivotal; I could use the birch bark, which is usually discarded, as my primary material.

‘Habitat’, birch bark, willow and steel. Approx. size: 3 x 2 x 2 metres. Darmstadt, Germany. 2014.

The birch bark turned out to be an incredibly strong and flexible material. Peeling it intact was challenging, so I devised a special tool for debarking which significantly eased the process. I enlisted the help of other artists and volunteers who were intrigued by the task. Together, we managed to collect and prepare large amounts of bark, which was then used to create the artwork.

Gil: Nature itself would change around your art, as the seasons change.

Tim: Yes, an example is the bluebells you see in the photo of ‘Spiral Coppice Arch’ which is in Kent. The coppiced sweet chestnut tree, commonly grown in Kent, produces amazing bluebell woods. They emerge because, in the spring, there are no leaves on the trees, allowing sunlight to flood the ground. This creates a display of bluebells each year.

‘Spiral Coppice Arch’, sweet chestnut and steel. Approx. size: 3 x 2.5 x 2.5 metres. Riverhill Gardens, Kent, UK. 2016.

The sweet chestnut tree was first introduced to the UK by the Romans. They used the nuts for their bread and the wood for building, so we have managed these trees for the last thousand years. It’s an amazingly sustainable material because once you chop it down, it quickly regrows with multi stems. You can harvest the same tree multiple times over hundreds of years. They are normally cut on a rotation that can range from 3 to 30 years, depending on the size of the branches or logs needed.

Gil: Your art is multi-dimensional, encompassing a variety of spaces and directions – inside, outside, up, down.

Tim: Yes, in both the shape and materials. The inner layer of ‘Forest Wave Shelter’ is made from a very heavyweight cotton canvas, which I sewed onto the steel frame. The canvas, when treated with varnishes, becomes durable and has a pleasant tactile quality, unlike synthetic waterproof materials. This canvas works nicely in contrast with the outer rugged wood surface, mirroring the natural layering you see in nature, like the chestnut seed casings that have a rugged exterior and a softer inside.

‘Forest Wave Shelter’, sweet chestnut, steel and canvas. Approx. size: 2.5 x 2.2 x 2.5 metre. Mount Yonmi, South Korea Yatoo Art in Nature. 2017.

I’m very grateful for the generous invites I get to make my art. It is wonderful to live and work in different places and cultures, interacting with the amazing people who have helped me bring my visions to life. I look forward to the next opportunity, wherever it may be.

At a glance:

© Journal of Creativity and Inspiration.

Images/art © the artist.

Tim Norris is an artist trained in Fine Art (Sculpture). He has been working since 1995, creating art for public spaces. His work sits on the boundary of furniture, sculpture and architecture. Tim often uses indigenous natural materials and tries to find a synergy between the artwork and its location. Tim lives and works in London and continues to exhibit, teach and create commissioned work in the landscape throughout the UK and the world.

Gil Dekel is a doctor in Art, Design and Media specialising in processes of creativity and inspiration in artmaking. Dr. Dekel is an Associate Lecturer, Reiki Master/Teacher, and a visionary artist. He was awarded the Queen Elizabeth II Platinum Jubilee Coin, in recognition of his dedication and commitment to pastoral work at Hampshire Constabulary. Dr. Dekel co-wrote ‘The Energy Book’, available on Amazon.