PERSPECTIVE

The art of looking closer: beauty in cityscapes

10 December 2024 – Vol 2, Issue 4.

Walking through the city, we often find ourselves on autopilot mode – glancing at the concrete, the road markings, and the familiar lines that guide us as we walk from point to point. Yet, beneath their practicality, these materials and marks convey stories, beauty, and art.

‘Urban Code’, sculpture by Rabia Raja. Concrete and thermoplastic tape. 40cm x 28cm x 8cm. 2024.

My goal is simple: to humanize the materials we encounter every day and to offer people a new way of looking at the city, seeing it as a living, breathing artwork. I work with materials that represent urban spaces – concrete, the thermoplastic pigments that make the road markings, and even the imperfections left behind by everyday life. Ultimately, my work is about shifting perspectives. I want to encourage people to pay attention to the overlooked, the mundane, and the seemingly unimportant details of the city.

‘Urban Code’, sculpture by Rabia Raja. Concrete and thermoplastic tape. 33cm x 28cm x 8cm. 2024.

Concrete

Concrete is often perceived as a cold, industrial material, primarily used for the construction of the modern world. I try not to see concrete in such rigid terms. For me, it’s more than just a solid foundation. I see it as a ‘liquid rock’, a material full of potential when it’s still in the fluid stage, before it hardens and made into sidewalks or buildings. Liquid rock is not static, but something that moves and shifts. It holds a raw natural power. As a liquid, it has a whole other life before it fulfils its functional role in cities. When I work with it, mixing it by hand, and shaping it without heavy machinery, I feel like I’m having a conversation with it. The process is tactile and personal. The material sometimes resists my plans. It solidifies the way it wants, and sometimes shows cracks and shifts, forming its own patterns and irregularities.

Process of making a concrete sculpture. Rabia Raja. 2024.

I believe that this shift reflects the city itself. Cities may appear permanent, but they’re always changing – morphing in response to time, nature, and the lives of the people who inhabit them. Likewise, the imperfections in my sculptures, the cracks and dents, are not flaws to be corrected; rather they are signs of the dynamic nature that is found in the urban environment – the tension between human industrialisation, and the natural forces that cause its degradation. The imperfections become the focal point of the sculptures; their visual flaws being a reminder of the irregularities in the world around us. These flaws invite new narratives about the built environment, looking past its utilitarian origins.

‘Urban Code’, sculpture by Rabia Raja. Concrete and thermoplastic tape. 35cm x 20cm x 8cm. 2024.

‘Urban Code’, sculpture by Rabia Raja. Concrete and thermoplastic tape. 36cm x 25cm x 7cm. 2024.

In urban spaces, concrete not only shapes the environment but also acts as a record of history, a silent keeper of urban memory… Gordon Matta-Clark, in his ‘Conical Intersect’ (1975), has peeled back the surfaces of architecture to expose forgotten stories. He was cutting through buildings to reveal hidden layers and histories. Doing so, he gave us new eyes to see… Another artist, the wonderful Dame Rachel Whiteread is famous for her cast sculptures of absent spaces and the traces left behind by people. She turns what we usually ignore into sculptures. I try to reveal the often overlooked stories in urban spaces, so we can see things in new ways.

Marks

Cities bear the marks of their inhabitants – scuff imprints, footprints in wet concrete, fading road markings and worn-down surfaces. These blemishes tell stories. They capture the presence of the people who have passed through them, leaving behind traces. A construction worker’s footprint, the wear and tear from years of traffic – these are not just signs of decay but evidence of life.

Tire mark left on a road’s marking. Photo by Rabia Raja. Southampton. 2024.

Road markings

Road markings in urban spaces are a form of visual language, guiding and regulating movement without the need for words. The lines, arrows, and crosswalks form a ‘code’ that is universally understood, guiding us as we walk or drive.

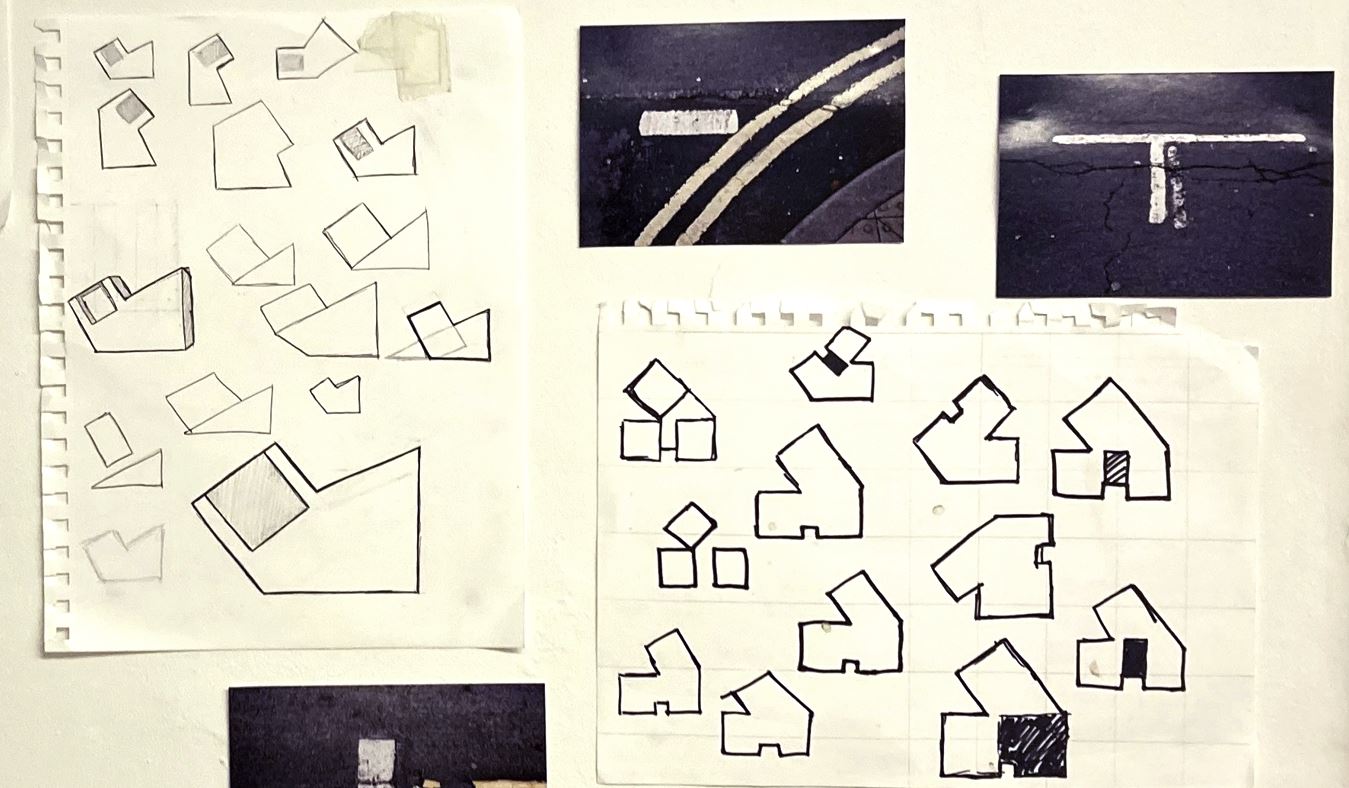

Road markings. Photos by Rabia Raja. 2024.

In a way, road markings represent a form of invisible control. Yet, in my sculptures, I take them out of this control, allowing them to free flow on the sculptures. I work with thermoplastic tape, which I apply to the sculptures.

In themselves, road markings hold abstract artistic quality. I take photos of these marks, whether a worn crosswalk or cracks in a bridge. I then draw sketches based on the photos, and use the sketches as inspiration for the sculptures. The photographs create the space for the world to be viewed through a more inspired lens. By observing a line of paint that has slowly worn away by countless journeys, I celebrate the individual stories of people within cities, counteracting how the busy nature of urban spaces removes our individuality. As George Oppen reflects in Of Being Numerous, the city is a collective experience, where countless lives intersect and leave their marks. Similarly, my work seeks to reveal the traces of these interactions, emphasizing the shared yet fragmented experiences.

Sketches and photos by Rabia Raja. 2024.

‘Urban Code’, sculpture by Rabia Raja. Concrete and thermoplastic tape. 32cm x 30cm x 8cm. 2024.

Art isn’t confined to galleries and museums. It’s all around us, woven into the streets, the buildings, and the sidewalks we walk on every day. Art is in the marks left behind by time and by people – the footprints, the scuff marks, the fading lines. Transforming functional elements into art creates the potential for inspiration in places where art might not usually be expected.

Process of making a concrete sculpture. Rabia Raja. 2024.

Next time you’re walking down the street, take a moment to look around. Notice the way the light hits a worn-out road marking, and the hidden stories etched into the pavement. You might be surprised at what you find.

My thanks to Gil Dekel for his support and contribution to this article.

At a Glance:

Art = Materials (Concrete + Markings) + Imperfections (Cracks + Wear) → New Perspectives (Hidden Narratives + Beauty).

The materiality of urban elements, such as concrete and road markings, is interpreted with the imperfections of streets’ cracks and wear, resulting in art that reveals hidden narratives and beauty, offering new perspectives.

© Journal of Creativity and Inspiration.

Images/art © the artist.

Rabia Raja is a sculptural artist specialising in industrial materials like concrete and metal, exploring built environments, and brutalist architecture. She holds a BA degree in Fine Art from Arts University Bournemouth. Her practice is currently based in Southampton.