INTERVIEW

Filling places with experience: Emma Moxey interviewed by Gil Dekel

10 December 2024 – Vol 2, Issue 4.

Gil: You don’t use many colours in your art; and when you do, the colours are rather ‘calm’.

Emma: Yes. My work is not loud in terms of colour… You need to approach the work quietly, thoughtfully, and even get quite close to see the details. There’s a lot of handwork involved in creating it on the canvas; it requires real focus.

When I do use colour, it’s usually to fill shapes that represent places. I am interested in places and landscapes. People imbue places with experiences, so, filling shapes with colours is a similar act to filling places with our own experiences. It’s almost like the places have been invested by me with a story and personal meanings, and are now represented as a shape with colour.

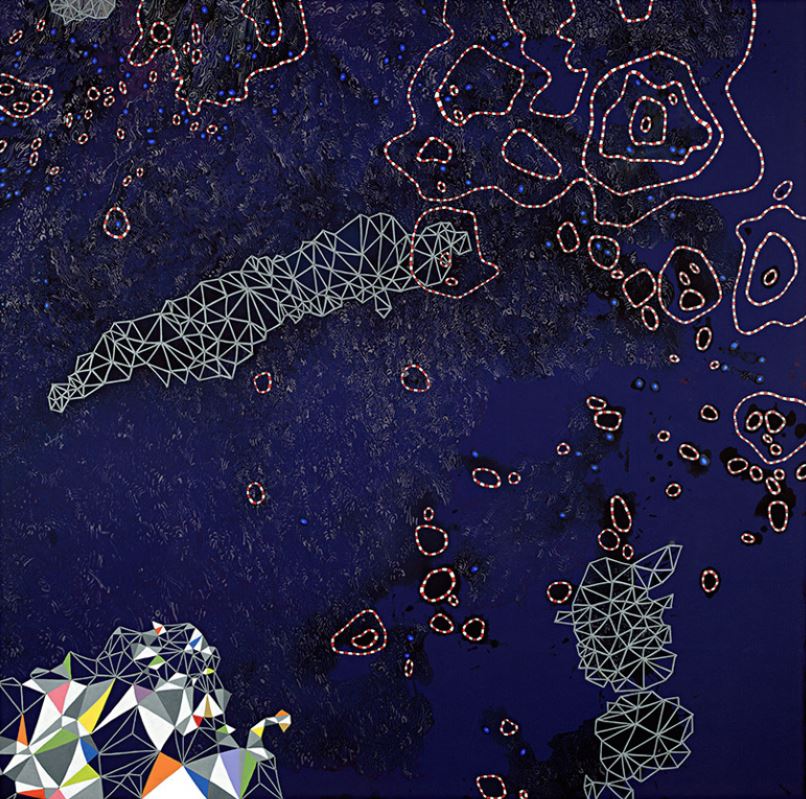

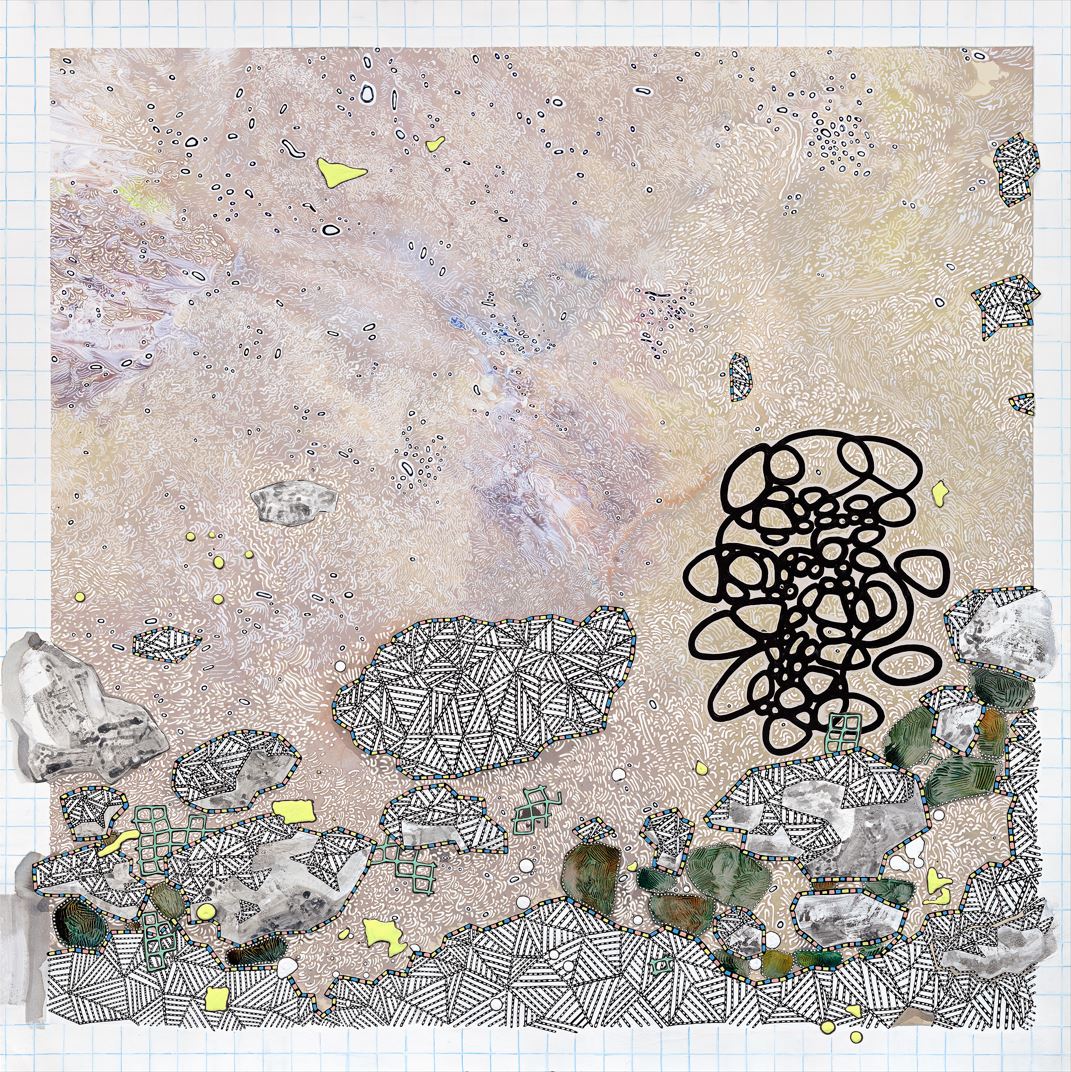

‘In the Wind’, by Emma Moxey. Acrylic and ink on paper. 82x83cm. Year undated.

Gil: You describe your process as an ‘act of mapping’?

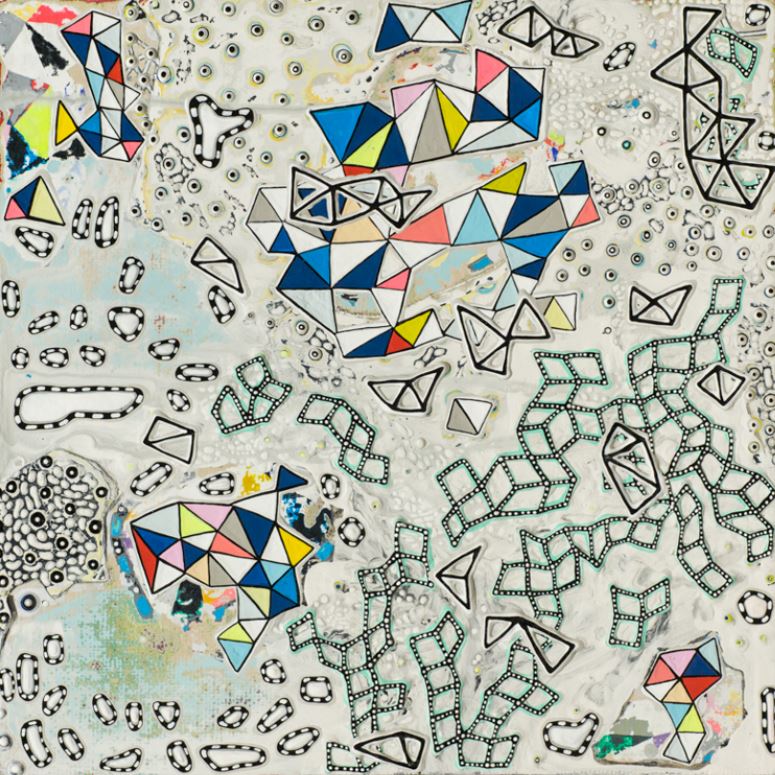

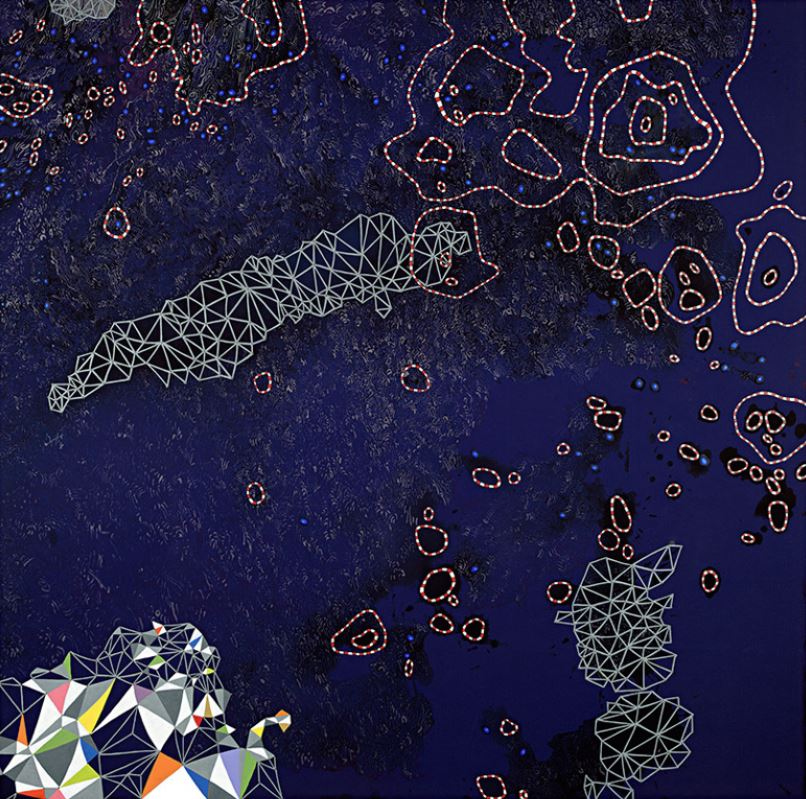

Emma: My work loosely resembles map work, but it’s more about how we engage with landscapes, and what we do when we map out things. My early work was closely tied to places that I visited and knew well, yet after moving away and having young children, I couldn’t just wander off as before. Instead, I started exploring the world through maps, engaging with the landscapes through printed maps and also google map. This has created a kind of detachment from the landscape and led me to think about how we respond to it. I became interested in how we start to infuse places with our own narratives, and how the mythology of the place starts evolving. I tried to capture this evolution in my art. I started creating very loose backgrounds of poured paint, trying to not control the paint as much as possible so as to let it evolve on its own, to build its own topography. I then tried to map this, using lines, dots and dashes. These are cartographical elements.

This kind of work is very time-consuming: I paint tiny dots over tiny dots, dashes over dashes, carefully laying down marks that build up over months. The process becomes an immersion for me; an immersion in that imagined place. Each tiny mark linked to my breath, my focus… Working at that small scale, over a big canvas, you’re really living in the painting.

‘Paths and Stories’, by Emma Moxey. Acrylic and ink on paper. 50x50cm. 2010.

Gil: And the works become layered.

Emma: Layers are important to me. I’m enjoying playing about on the verges between 2D and 3D, exploring the moment that the work crosses between the dimensions, building up the marks so that they break with flatness and take on a form for themselves. I am working on a new piece now in which I am pushing the painting to cross from image to object. It’s three-dimensional, yet made entirely out of paint. The dots aren’t just quick dots; each one requires a precise, controlled breath to place it accurately. I’m making them three dots high, and each dot must fill the exact size of the last dot below it. Experimentally, I’m creating dots that have dimension, like little towers…

‘Land Marks I’, by Emma Moxey. Acrylic, ink and vitreous enamel on steel. 50x50cm. 2013.

Gil: How do you choose what layers to create?

Emma: I’m laying down marks according to certain rules, following the rules of mapping out new territory. It’s actually quite emotionless. I’ll look at a mark that’s appeared and then decide what to do with it. For instance, I’ll avoid painting over certain stains on the canvas – so all my dots have to be in the patches where there’s no stain – or I’ll follow the contours of certain colours. It’s almost mechanical; each mark is a response to the ‘landscape’ I’m creating. I don’t know or predict what that is going to look like. I’m just following the rule. For example, on some pieces the paint may have peaked in a certain way, and I’ll follow each peak with a line, then add another line where two colours meet. I have to follow that with a line. And so, there’s a rule. I have to do it. This is why it’s more of a mapping process rather than ‘creative image-making’ so-to-speak. I follow the rules that respond to the painted place. I’m just living it out.

‘A Place in Mind’, by Emma Moxey. Acrylic and ink on paper. 82x83cm. Year undated.

Gil: So, the rules come from what is already present on the canvas?

Emma: Yes, it’s like discovering how to navigate a terrain. The rule is that I’m an explorer and I have to work out how to draw or respond to the topography of a landscape.

I like the idea of archaeological digs in a landscape, where the landscape becomes marked. There are important points of focus. Something was found here, or there’s an anomaly there, and little markers are used to indicate these places. People dig, spending a lot of time invested in tiny landscapes. It is similar to a little brush working; looking for things in the canvas. When I’m painting, I create that connection.

I studied medieval maps. These maps were created before our present GPS mapping system. In medieval maps, you can see the human attempts to work out how to represent a landscape with lines and dots. There’s a lot of variety in how they did this, and many of my marks come from these early mapping traditions. In the earlier maps, dot density was used to indicate certain geographic areas. They were less interested in contours. Instead, a lot of their lines were heading somewhere, they used line direction to show topographic elements such as hills. My marks come from that tradition. It’s about bringing some order to a wild landscape, investing and colonising it with marks in the same way that an early mapmaker was trying to tame what they saw.

Sometimes I work directly in the landscape, leaving small natural sculptures or interventions in place. I like the idea that someone might find these works; they are stories waiting to be discovered… There is a ritualistic aspect to this; I’d make and leave pieces, and therefore anchor myself to places, building up my own stories in places. I have certain places that I return to, such as the woods and moorlands near Burley in the New Forest. This is an area rich in myth and folklore. These narratives, historical connections to landscape, interest me. They are both cultural and personal. For instance, Burley has a history of smuggling and witchcraft stories. These stories underpin our landscape experience, but we also interweave this with our own different stories.

‘Sun Dance’, by Emma Moxey. Acrylic and chalk paint on wood block and canvas. 20x20cm. Year undated.

Much of my work connects to my experience directly in the landscape, and while rule based, they are inspired by thoughts, actions and events that result in these places. For example, Sun Dance, was created directly in the landscape, by the sea, during an art residency on the Lymington salt marshes. I was trying to look at the sea and capture the patterns in the waves, but I couldn’t really see it because the sunlight was bouncing off the water into my eyes. The work reflects this moment, the patterns and the bright patches that burned into my retina…

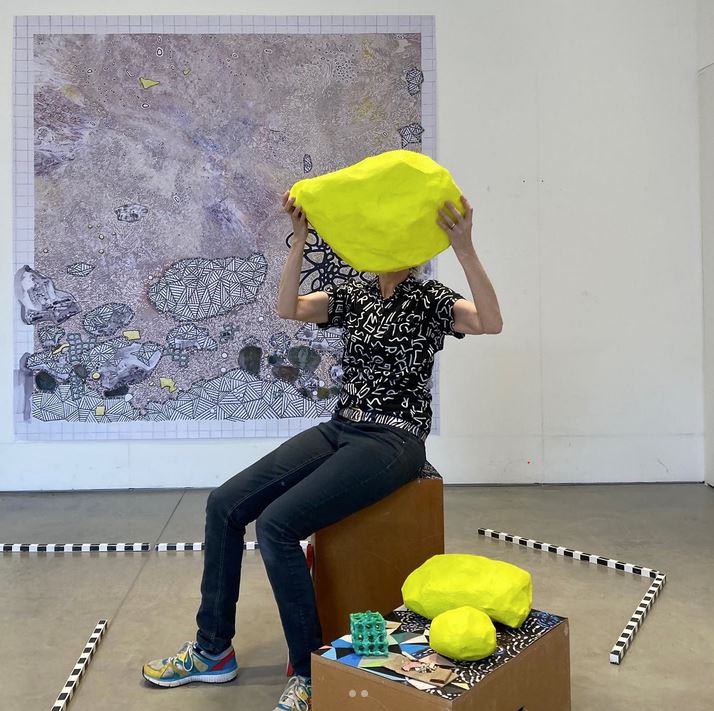

Gil: You did some 3D work for John Hansard Gallery.

Emma: Yes. I created objects from my paintings. Initially, I gathered scrap materials from building sites – wooden triangles (which I painted), wooden rods (painted black and white) – so the pieces became like grown-up building blocks. My work was about construction and building places, so I liked the idea that I was using scraps from building sites that had to do with building.

People were invited to interact and play with the pieces – move elements around and build their own landscapes. So, what was once a dot could now be picked up and held. The pieces had become literal objects. Visitors were almost doing the mapping for me, which was good fun. It was like a full circle, looking at how we engage with landscapes and then giving people an empty landscape with elements to build their own.

Emma’s Artist Pop-up project at John Hansard Gallery, Southampton. 2022. Photo used with permission from John Hansard Gallery.

People loved it; they built paths, playing with shapes, almost like a playground for abstract landscapes. I think being a mum influenced this idea too, watching how playgrounds are designed to guide you in certain ways. Playgrounds, and parks – they’re guided spaces where you’re subtly told how to experience them.

Gil: Nature is also a playground?

Emma: Yes, a playground to play and create. My work Longshore Drift was inspired by the ebb and flow of waves. I was walking along the beach near Bournemouth and noticed how the waves would leave stones in patterns, almost like they were arranging them. The bottom part of the painting represents what’s left by a wave when it draws back, leaving things behind.

‘Longshore Drift’, by Emma Moxey. Ink, chalk paint and acrylic on paper. 75x75cm. Year undated.

For me, this symbolises chaos evolving into order. I was watching as the stones were left by the waves, and formed into groups instead of appearing alone. The wave would leave two or three stones clustered together, and I found that fascinating – the randomness of the wave creating an ordered pattern on the beach.

I was also finding long seaweed on the beach that collected in the same way. It was as if the natural world was depositing all the emblems that I then used in my work, right there at my feet.

Gil: Do you see your work as structured or chaotic, then?

Emma: Both… They both work together. Order and chaos are interesting forces. They operate in time, yet time in itself is baffling… I sometimes sit and listen to Brian Cox talk about time not being linear. There’s something about time and space connecting in my work. You spend a long time working on something, but it’s still just at one physical point you’ve been focused on…

‘A Place in Mind’, by Emma Moxey. Acrylic and ink on paper. 82x83cm. Year undated.

Gil: Is there any element of automatic drawing in your process?

Emma: In some ways, yes. My process is automatic – deeply intuitive – even though, if you think about automatic drawing, it’s almost like being a machine. The rule I impose at that moment has arrived automatically, from a creative source. But when I put it into action, I’m almost like an automaton, operating out of the programme.

Gil: You also create graphic works with some bold shapes.

Emma: A lot of those graphic works came from sketchbook work, which was more intuitive, where I’d try out different things. Certain shapes that felt pivotal would then be drawn out to become finished pieces of work.

There’s quite a bit going on in my work, from graphic work to more loose, intuitive work, and then playing with three-dimensional pieces, all using the same language but realised in different ways. I work in repetition a lot. For example, one page in my sketchbook leaves marks on the next page, and I will pick that up and work it into a new sketch. I’ll start with something, and as it leaves stains or random marks, I then respond to those, letting each page evolve from the last. It’s a bit like walking on the beach and finding details that trigger a response.

At a Glance:

Art = Mapping (Place) + Balance (Intuition + Structure).

Art is the mapping of landscapes that hold personal and symbolic meaning, combined with a balanced approach of relying on intuition and following a methodical structure in painting.

© Journal of Creativity and Inspiration.

Images © the artist, and John Hansard Gallery.

Emma Moxey is a UK-based fine artist with an MA in Fine Art, from the University of the West of England, Bristol. Known for her detailed mapping-inspired works, Emma has exhibited widely and held residencies. She teaches extensively in art education and has been showcased internationally, with works in exhibitions across Europe.

Gil Dekel is a doctor in Art, Design and Media, specialising in processes of creativity and inspiration. He is a scholar, designer, visionary artist, Reiki Master/Teacher, and co-author of the ‘Energy Book’. Dr. Dekel is an Associate Lecturer at the Open University. In 2022 he was awarded the Queen Elizabeth II Platinum Jubilee Coin, in recognition of his dedication and commitment to pastoral work in the UK.