Photographic installation artist Katayoun Dowlatshahi interviewed by Gil Dekel.

Gil Dekel: You are tracing light onto glass using a method called Carbon Photography. How did you develop the idea of ‘light drawings’? [1]

Katayoun Dowlatshahi: In 1998 I spent a year as Artist in Residence at Durham Cathedral. It was there that I began a journey investigating the relationship between photography and drawing. I wasn’t happy just to collage together photographs with drawings. I wanted to investigate the historical roots of photography in relation to drawing and to produce light drawings without using a camera. How can you draw something so intangible, like light? The work I produced for the residency was a prelude to research undertaken subsequently during 4 years of research at doctorate level. I adopted a 19th century process called Carbon Photography and experimented with this technique onto glass, metal and paper using direct sun light. Light was transmitted directly through a glass installation and its effects captured onto these various surfaces. [2]

Figure 1: ‘Drawing Fragments of Light I II & III’ (2004). Triptych. Gelatine, blue & black pigment onto glass, 1680x760mm each.

What attracts you in light? [4]

I have always been interested in light and shadow, and the dialogue between the two. Light is around us all the time. We live within it; we take it for granted. There is something incredibly powerful about the concept and the physical phenomenon… I am very careful not to use certain words to describe the nature of my work… but I do feel that my work touches on the spiritual without being religious. [5]

A lot of my early work was very dark, but it was not about darkness, but about light. To appreciate and understand light you have to embrace its shadow. In recent years I have been doing more work where light has become more predominant. [6]

I found the process, through which I discovered invisible characteristics of light, to be very symbolic and visually exciting. From an esoteric point of view I am fascinated with the concept of a single source. The existence of one light source or energy. All beings are simply an extension of this light; they are a material reflection. The following analogy may explain more clearly what I mean: the light source can be represented as a mirror; by shattering that mirror many individual fragments or shards are created. You and I and all other beings are represented by these individual fragments. However, we reflect that one light source from many different perspectives; that is what makes us all unique. This concept, simple as it may be, is core to the way I perceive the world around me and is the most important visual image that I will carry throughout my life. [7]

Is that image helpful in making your art? [8]

It is always there, but I am not trying to represent it in my art. It is just there. Symbolically, I think it is represented throughout. If you go to different parts of the world light is perceived differently, because of the difference in regional architecture and the landscape. Also, the relationship people have with light is different around the world. The challenge for me is to draw out something unique from all that, even if the work tends to be more about the shadow than the light itself. [9]

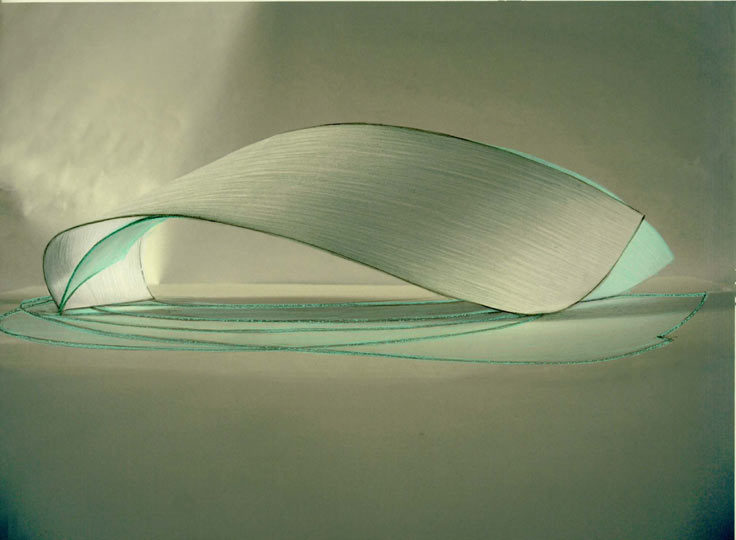

Figure 2: ‘Proposal for Sunniside Gardens Commission, Sunderland’ (2006). Steel, curved glass with etched finish, ground area 4250x8600mm sq.

You did a lot of residencies and commissioned work in specific spaces. What is your relationship to the architecture and the space of the works? [11]

I relate to the space, its history and its context, allowing these elements to feed into the work. For example, I did a piece of work in Santa Fe, USA, when I was on a residency there. I produced a variety of different types of works there: drawings, video, photography. I was really blown away by the architecture of the building, which was designed by a contemporary Mexican architect by the name of Ricardo Legorreta. He had really considered the nature and function of light within the building, which had long thin apertures punctuated within walls and along corridors; you could literally observe slices of light entering into the building. I responded to that in particular in my work, as well as a video and some drawings. I also produced a piece of work made up of ten photographic images of this light. [12]

With commissioned projects it is not always appropriate to apply something which is really personal, because the work is really about the space, and less about me. [13]

Is it possible for artists to focus on the space and ‘remove’ themselves? [14]

I think it is important that I am flexible enough to respond to a specific space, and that I do not impose my personal identity on the work in question. My identity may well come through, but at least I am creating a much more personal and honest response to the space. In other words I allow the context to influence the work. For other artists, such as Anish Kapoor, this may not be so important because his work has a very strong identity, and that is what people want from him. [15]

When I was working in Durham I spent a great deal of time in the cathedral, I was very impressed by the sacred structure in relation to the landscape it was built upon. Churches are solid buildings, yet they represent something intangible, spiritual. Trees rooted in the earth transform the space below their canopy of branches when the sun’s rays pierce the empty spaces between the leaves; the pillars of a church are as these tree trunks, and the vaulting above is like a canopy of branches. You just have to look inside Kings College Cambridge as a fine example of this analogy. [16]

I am always fascinated by the vertical line. The verticality of the pillars of the church, and the light and shadows cast from these. It is as if I am walking through a forest observing the light, shadows and intangible shapes; these are the qualities that I internalise in my mind’s eye. [17]

And how do you bridge the internal image in your mind with the external image? [18]

The important thing is not to try to force yourself to illustrate these ideas, but to allow your intuition to guide your process. [19]

I once joined the Theosophical Society through my mother’s encouragement. I was attracted to it because theosophical ideology and values, which are not wholly rooted to one religion but are borne of many. I liked the idea that I could connect to deep human and shared spiritual values without the need for pure dogma. [20]

How do your spiritual beliefs affect the way you see life around you? [22]

It is really part of who I am; I don’t necessarily make a differentiation. When I was younger and still training, I had very strong mood swings; both negative and positive emotions. I could not communicate my feelings or my beliefs through art since I had not developed the necessary skills to do so, therefore, I communicated my heart felt sentiments through poetry. Words were very immediate and powerful for me. [23]

At eighteen I visited Israel, lived for a few months in a Kibbutz, a month in Egypt, followed by two months in the Armenian quarter of Jerusalem. The experience had a huge impact on me. It was as if I underwent a psychological and spiritual journey. At the time I thought that my visual art would, on my return home, reflect this journey but it didn’t. Conversely, poetry that I wrote at the time did reflect these experiences but I could not translate words into pictures. [24]

I still find it difficult to articulate my spiritual values and beliefs. When you are facing a blank canvas, you are thinking, ‘How am I really going to do this? How am I going to convey all those thoughts and images?’ I could not do it at first. I did not have the ability or the tools some artists have in formalising ideas through drawing or painting. It took me many years to get to where I am now. I can now convey these inner sentiments but I had to develop new avenues intellectually and practically within my practice, to enable this to happen. [25]

And how does the creative process unfold? [26]

I have always felt that I am not the kind of a person who could spontaneously create a work of art. I build my work around a concept and take on a process or technique that would enable me to develop those ideas fully. This is how I work in residencies. When I am in a residency, I am experiencing a new context, allowing myself to be in that place; in the landscape or urban environment. [27]

I allow the process to slowly unfold, I don’t push it. I just do not think you can. You have to experience it first. First and foremost it is about having a sense of your envirnonment, memorising that space, allowing the internalisation and processing of those images to influence a work of art. [28]

In Durham I was thinking about the architecture, the internal space, and the light, but I didn’t know how to convey that. So I was holding the memory of the interior space of the cathedral and without using any visual references I drew what was in my head. I didn’t think it, I just drew it. I didn’t know what I was doing, but I allowed my intuition to lead me; I had trust in the process. Once the drawing had begun I could assess it. Though the work was fairly formal to begin with, I found that over time I began to consciously abstract the lines more and in doing so broke down the formality of the earlier work. [29]

Figure 4: ‘Light: Past and Present’ (2003). Triptych. Enamelled colours on glass, 1800x3600x250mm each.

How do things inspire you? [31]

It is a visual response wherein I see something that strikes a cord in me. I use photographyin many ways, either to document or record a moment in time or as a technical means of creating unique images. For example, I once visited a region of southern Spain in the mountains and villages above Granada. A friend and I found many derelict houses that used to be lived in by Moors high up in the hills. The Moors were expelled by the Christians many centuries ago and these houses were left abandoned. The interiors of the houses, some no bigger than large huts, had deteriorated and were dark with only shafts of light piercing through holes or around doors or windows. I loved what I saw. I photographed these dark interiors and though I never exhibited the work, the images greatly influenced my work. [32]

I periodically experience epiphany. I would do something very practical with my work and during my analysis of it I would begin to see connections with thoughts and ideas, and be overwhelmed by strong emotions. The artwork always manages to connect to some deep unconscious level, and at the moment I would become conscious of new things in my work. I would end up in tears, sometimes of joy, sometimes of humility knowing that I as the conscious artist was not fully in control of my process. I was only able to bring my understanding to it after the work had been created. [33]

The process of creating work is akin to having blurred vision, at a certain juncture during the process the veil that has clouded your vision has been removed; in that moment you discover something about yourself and the work you have done, which is incredibly empowering. That knowledge feeds you and is inspiring… this is a fascinating subject. It’s not very often I end up talking about it… [34]

What is that moment when the veil is removed and you discover new things? [35]

I think that we have the potential to be very conscious beings, but only a small part of us is truly conscious most of the time. We are unaware of our whole being, be it in the mind or spirit. My moments of epiphany happen when I think that I have reached a deeper connection with myself. I don’t fully understand it but sense the immensity of that potential. It is hard to define because I am talking about something that is essentially invisible, intangible. It is as if we get a glimpse of other fragments reflecting light from the same light source as you. [36]

When is it that you have such moments? I mean, would that be while making art or maybe otherwise in your daily life? [37]

That is a hard question because my art is my life. I do not separate the two. [38]

It is not like washing the dishes and suddenly having an epiphany. I never had that. When I am in my creative process I have these moments or when on a journey; less so in recent years. At present I am very content and emotionally calm in my life, consequently I am less in touch with extreme positive and negative emotions. A visual artist, like any other creative practitioner, often reflects on some aspect of his or her life, which in turn can act as a powerful catalyst for a work of art. For many years this form of self reflection was a strong motivation for me, it was a very productive and life enhancing time for me. [39]

As an older woman with experience and emotional maturity I now seek other ways to find inspiration. I used to hit a brick wall in a dark place, so to speak, and would get a response, an emotion, sometimes of anger or sadness; that would inspire me to do things. But in my contentment I struggle to find inspiration, I don’t have a brick wall to hit against. Some people can be inspired by the beauty of nature. Wordsworth wrote the most amazing poetry because he was in beautiful settings, yet as artists we are not motivated by the same things. Though nature inspires me, it is the edge, the unknown that beckons. [40]

So I have had to work harder in these last few years to find a certain maturity and depth to my practice that enables me to reflect on deeper more universal experiences. [41]

Why can you not bounce of happiness in the same way as of sadness? [42]

I don’t know… I can feel emotion from that which is beautiful but the inspiration may not necessarily come from that relationship. [43]

Emotions are integral to our conscious and sub-conscious minds, so no matter how, they always finds a way to show themselves. [44]

5 September 2008. Images © Katayoun Dowlatshahi, Text © Katayoun Dowlatshahi and Gil Dekel. Interview held in Portsmouth, UK, 30 May 2008, and via email correspondence (June-September 2008). Katayoun’s Website.

- Reading with Natalie, book here...

- Reading with Natalie, book here...