Author and designer Gavin Ambrose, MA, interviewed by Dr. Gil Dekel.

Part 2. Back to Part 1.

Gil Dekel: What does it take to be ‘good’ graphic designer?

Gavin Ambrose: To be a good story teller – that’s all. Be it a brand, a poster, a book – tell a story. All the best designers in the world make time to understand what it is they are trying to say, and then find a visual language to convey it. If you do it the other way around, you are just ‘noodling’, creating visual noise.

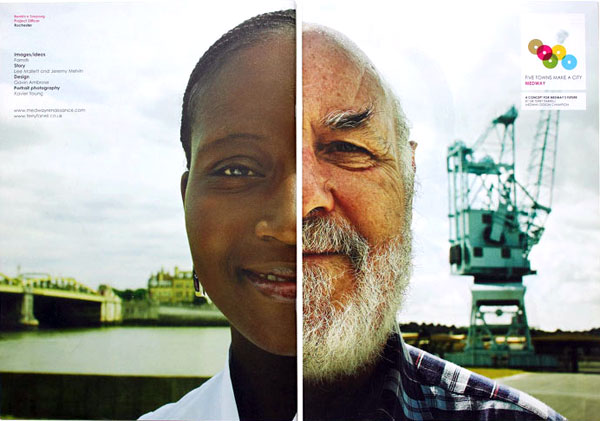

Gavin Ambrose – Logo and print material, 2011. Work for Sir Terry Farrell on a proposal to bring together the 5 Medway towns in Kent, England (Rochester, Rainham, Strood, Chatham and Gillingham) to form a single city. The covers feature portraits of local residents and workers, with local landmarks in the background.

Gil: What should graphic designer student ‘take’ from their degree study? How can they best ‘benefit’ from it?

Gavin: Design students need to learn two things:

1.

Be curious. Be curious about everything that surrounds you. Try to work out how things work (or don’t work).

2.

Don’t accept defaults. I see too many students producing work where the software is deciding for them. Be it page sizes, colours, typefaces, type sizes or leading. As a student you should be in control of this, not Adobe…

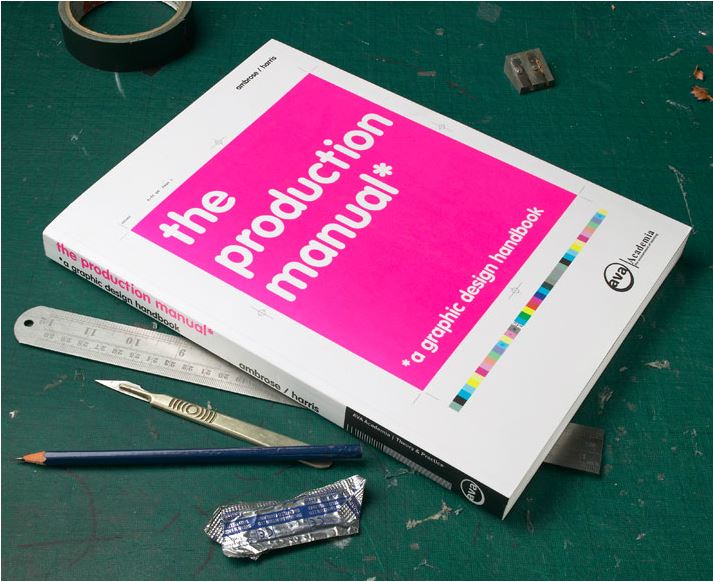

Gavin Ambrose – Photo of ‘The Production Manual’ book, co-authored with Paul Harris. 2008. Publisher: Fairchild Books AVA

Graphic design is a ‘skills’ that one can have, and not necessarily learn at a University. Is there a difference between Uni-trained designers, and ‘un-trained’ designers?…

Yes and no. There are some great designers that haven’t had exposure to graduate level training, and equally there are lots of students, who do degrees who don’t go on to be good designers. But as a general rule, I personally believe that the exposure to staff and other students that a degree offers, creates better designers. I also believe there is an over supply from Universities that fuels a flattening in graduate wages. But this is cyclical, and isn’t unique to design or indeed the creative arts.

I think, in part to balance this, there should be some courses more suited to vocational work. In my working life I’ve worked with Uni-trained and non Uni-trained creatives, and generally there is an insight or understanding that Uni-trained designers have that their untrained counterparts don’t have. The skills that you need (in a basic way) to be a photographer, a designer or web programmer aren’t that high. They are basic. Anyone these days can put some text and image on a page, or record a film – but that doesn’t make you a designer or a film-maker. Those skills are deeper, and take longer to foster.

A big part of a degree isn’t to learn skills, it is to have a period of time to develop as a person. In the interview I recently completed with Ken Garland he made a really insightful observation, that it isn’t skills that are important, but the ability to acquire them. An example of this would be at Brighton University where I teach students do design, but also more traditional skills, letterpress printing, bookbinding. So for a student, the ability to learn letterpress may or may not have an impact on their lives, but the ability to learn that skill certainly will. Some of these skills also force students to concentrate, to look at the detail, to think about what they are doing.

Some people consider El-Greco (1541-1614) the ‘first modern graphic designer’. What do think? Are there any historical ‘roots’ to graphic design which you could indicate? Do you feel you ‘belong’ to a ‘tradition’?

This is an interesting question, and I guess it relates to how you define a graphic designer. Ken Garland spoke about how he’d been interested in the roots of design, and was looking at how design could be said to start in the 1950 as a formal term, but as he went on to elaborate it was much, much earlier. Even earlier than El-Greco.

Garland explained that it has always been there, this profession of design, in as far back as Greek and Roman antiquity. It is there in the dance, in gymnastics, in sport – it is the same set of principles. If I talk of ‘form’, ‘balance’, ‘harmony’, I could easily be talking about typography, or I could be talking about gymnastics. I’d argue that the thread that makes us designers is deeper than typography or image-making. It is concerned with us being the modern day story tellers. So in many ways a graphic designer is no different to early man, huddling around a fire, swapping stories.

As we progress from fully print (paper-based design), to digital (screen-based design), how do you see the future?

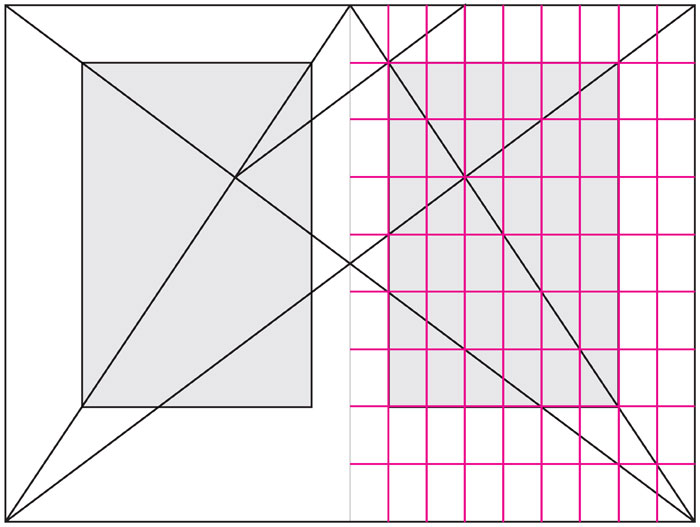

In some ways everything changes, in other ways nothing changes. I was researching Villard’s variations on the Van de Graaf Canon (a classic page layout based on harmonious proportions) and you are left thinking that in some ways all the great discoveries of design have already happened. It doesn’t matter what changes in terms of media, what counts is basic considerations of beauty, taste, style, proportion – and this is no different if it is for screen or for print.

The famous citation that ‘print is dead’, well, in part yes, yet I’d like to believe that people will still buy books. There is a tactile nature to the printed book, but it is under pressure in the shift not only from print to screen, but also in the shift of the economics of printed matter.

The shift generally is in the way people consume news, music and information – the content becoming free, and the revenue stream to the author or publisher coming from advertising. I’m not sure how comfortable I am with this overall position, but I suspect it will proliferate. Having said that, it is interesting to observe that the sales of records (arguably an antiquated technology) are on the increase.

Film-cameras, 15 years ago, seem to produce far superior print quality compared to equivalent recent digital cameras (such as Canon EOS 1100D).

There’s a valid point here. With digital cameras especially I see two sides to it. In some ways the digitization is liberating, you can take as many images as you want, delete at will and hope for the best. When we had film cameras this was different, you had to consider far more what you were doing, as you had a finite number of chances, and mistakes were expensive. Alex Singh, a New York photographer I recently interviewed, said:

“The mundane has been allowed to proliferate through social media and is now magnificent.

The magnificent has been captured by no one, reblogged by everyone and from every conceivable angle. It’s now mundane.”

I’m inclined to agree. In the same way as close reading of texts has suffered, so has the ‘reading’ of images. Our ability as a society to judge what is good, bad or indifferent has changed. I think that critical judgement is being eroded, though there are still lots of designers and photographers who are challenging this. It’s refreshing to see as well that there are still students and practitioners who are committed to the pursuit of craft. Kevin Meredith in his interview for the Design Genius book, lamented on exactly this:

“When shooting film you’re limited to 36 exposures if shooting 35mm, 12 if it’s 120 roll film. This forces you to be way more considered with the way you shoot. I would probably take more time setting up a shot and waiting for the right lighting conditions. There are definitely situations where I will not use film as it will not be financially viable. On the flip side it is possible to emulate the film look with digital editing tools like Photoshop, Lightroom and various other plug-ins. In my experience digital film emulation tools never give constant results between images shot in different lighting situations. A lot of additional tweaking is required. Because of this extra time, it can be easier to use film from the beginning if you know a “film” look was required.”

How did you make the progress from graphic designer into authoring design books?

I’ve always been interested in collecting. I collected things as a child; stamps, postcards, and the first foray into publishing through the Design Basics book series was really an extension of this. It was a means of collecting and collating other people’s work.

When I published the first book in the series, Format, about 10 years ago, it was really a way of simply saying: here is some great work, from studios I’ve always admired. Within that book was work from Why Not Associates, North, Studio Myerscough, Lust, Frost et al; work that I don’t try emulate in my own practice, but work that is inspirational, and also work that has stood the test of time.

I was approached by AVA (now an imprint of Bloomsbury) to develop a book series, having worked with the commissioning editor and managing director previously at RotoVision. In a way the Design Basics series tried to be a reinvention of that type of publishing – educational, but inspirational. The inspiration side can only come from having the best studios contribute work, so I sincerely thank all those people who have helped over the years.

The current book we are working on, Design Genius, is in a way an attempt to reinvent that process again. The book is meant as an insight into the creative process through a series of interviews focusing on people’s approaches to their work, rather than their work. So, an interview with Erik Kessels, for instance, focuses on his thoughts – as these are the real insight into his creative output, rather than simple reproducing his work (which many of us are familiar with).

End of Part 2. Back to Part 1.

11 April 2014.

Exclusive Publishing Rights © Gil Dekel. Interview © Gavin Ambrose and Gil Dekel. Images © Gavin Ambrose. Interview conducted via email correspondence between 10 May 2013 and 10 April 2014. Gavin is based in Kent, UK. Gil is based in Southampton, UK. Gavin website: http://www.gavinambrose.co.uk/

- Reading with Natalie, book here...

- Reading with Natalie, book here...