Curator Karen Robson interviewed by Natalie Dekel.

Natalie Dekel: How can one curate an exhibition on something so intangible, such as memories? [1]

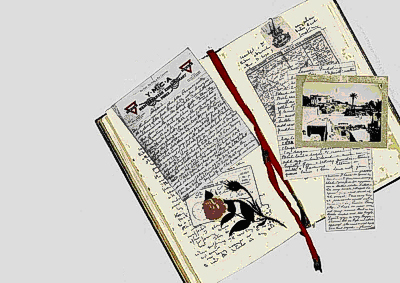

Karen Robson: We started originally with the idea of just doing diaries – and it expanded as we explored the material across the whole range of our collections. [2]

When people think of diaries, they immediately think of personal writings, but a diary can also be an official documentation, say of a sea captain, or a register by a clerk. There were many aspects to diary that we wanted to explore. [3]

It seemed that diaries are special as they bring out a wealth of information about the person who wrote them as well as the culture and social aspects of the time when they were written… [4]

As I look at the exhibition, I have noticed that some of the diaries are obviously personal writings and some are official documentation. How did you choose the diaries for the exhibition? [6]

As we started looking through the material, we saw how we might group them together in a coherent way. We chose a few themes: travel, exploration and wartime. But we also wanted to encompass a range of types of material. We didn’t want to present things from just an official point of view or a personal view, as it would have limited the way people saw the material. Instead, we wanted to mix various types of documentation: different types of writings, different types of records, that would give a more objective view of how people chose to document their experiences and a feel for the time and culture than of our views (as curators) on what is documented. [7]

There are two parts to the exhibition, the one is outside in the hall, and the other is in the area designated special collections area. The outside one shows only paintings? [8]

We chose images because they did not need any explanation. They show people what the diaries deal with, visual memories of what is documented in the written form in more detail. [9]

In a sense, by showing certain images we may appear to imply a message that we had not intended. [10]

You’ve titled the exhibition “Unreliable Memories”. What do you mean by that? [11]

That was a question we were asking. Are memories reliable? How reliable are people’s accounts when they write things? For example, we have diary material that is very personal; somebody’s diary, somebody’s engagement in a love affair which seems very much at the moment, but actually we think was written a while later. But it obviously reflects very much the emotion that the author was feeling at that particular time. [12]

There are also other examples of diaries that were put together later on. It makes a great impact on the information provided in a diary. I mean, how much does one edit and change what one is trying to present when one is actually doing things later on in a ‘cool’ reflection? [13]

For instance, something like the William Mogg diary in which he is talking about his explorations in the Arctic. This is a copy he put together many years later… This is a somewhat refined and beautifully edited version of what the events were. You wouldn’t know how much was left out or edited out, and what were his actual experiences at the time of his travels… Such an approach to presenting a diary makes you think how much are they presenting an edited version of themselves? That is why we have decided to ask whether memories are reliable or not. We do not answer this question, we are simply raising this question for people to think about. [14]

You juxtaposed diaries of, say, the captain or the priest and the young ladie’s personal commonplace books of knowledge. So it’s really interesting how different diaries present information… [15]

The commonplace book in one sense was seen as a nice hobby to showcase the talents of genteel, refined young ladies. They often contain examples of verse, sketches, watercolours, etc. But as each commonplace book is different you wonder why they put them together in that way? Why did they choose that particular theme? [16]

Again, it is a question of how much people try to present a particular facet or a picture of themselves or their knowledge. We were raising those questions by presenting personal items next to different types of material such as official records. Even if you have an official record of a committee, the emphasis is on the person taking the minutes to have a clear and concise record. But in a sense, everybody who takes notes is slightly editing things as they go along – so it’s again a question of how events are presented. [17]

Do you think that the way people created the images along with their writing speaks of their emotional state at the time? Say, when somebody did a very quick sketch – almost like a matchstick picture – as opposed to the lady’s flower, created elegantly and with full details. [18]

Some images are beautifully done and some not, all depending on the circumstances in which they were produced. The image may say something about the way that the person is presenting themselves: ‘I’m just doing a quick sketch, I was standing in a field or whatever, I quickly did this. This is what I’m going to present’. This shows me being there, doing this. Whereas, the flower image you refer to is a beautiful thing, obviously the result of much time and effort. It was produced in a much different circumstance, presented to showcase the accomplishment of its author rather than provide new information. So it may be about issues of presentation. Or it may be that one person can draw and the other can’t, all sorts of reasons… [19]

But again, it’s how they put things together. There could be issues about the type of material or the type of record that they’re trying to keep, shall we say. Maybe they felt that a rough sketch, produced in situ, showing that they were there, had a greater truth than if they went away and produced it in a more polished form at a later date… [20]

There are issues with artists who sketch, and then you find that it looks like it was done as a sketch but it was actually produced after many weeks in a studio… So maybe those are issues where you feel that it is truer because it is a rough sketch, but it’s actually produced in situ. [21]

If you had seen these sketches separated from the text would you still be able to relate to them? [22]

Possibly not. That’s why they’re put in together. Actually, if we’re looking at somebody like Lucas who’s got his sketch books and his notebooks, they sort of fit together. But some of those can actually stand up as individual works as well because they work in tandem, not necessarily reflecting each other. Perhaps he is a bad example as he died young and the question with him is: If he hadn’t died en route to another explorative project, whether later on all those different elements would have been brought together in a much more edited and organized way? [23]

The rough, raw unedited journals of Lucas are quite a contrast to those of Mogg who lived to old age, and got to put all these things together in a much more formalized way. [24]

Lucas died at the age of 25 en route to another projects. These journals are what were left. There’s a sort of rough and ready quality to them, because I think they were the raw material for a publication he was thinking about. But I still go back to the idea that he produced these things in situ and I think he felt there was a raw quality to them that somehow proved their authenticity. Like saying: ‘I did this, I was there’. [25]

And I think he was probably envisaging putting all this together into something more formalized but obviously he didn’t live to do that. [26]

I wonder, being an artist, when you look at the images, whether they carry with them all the memories and situations that they’ve been placed in ? The context? [27]

Well, I think for him they probably were. They would have been a way of providing the context, the background for his research. I presume he was envisaging producing some formal publications. [28]

These days we have the camera. It’s equivalent to that. It’s a way of creating… some people prefer a visual memory that sparks all sorts of thoughts and ideas about some place. [29]

In Lucas’s case, obviously he was keeping visual sketches as well as writing things and I think the two were married together. For him, presumably, the sketches added colour to the sometimes quite dense and incoherent notebooks that he kept. But I think the two come together. [30]

What about photographs? Would photographs be a more reliable memory than diaries? Would they still give some kind of a context that you are aiming at? [31]

Well, that was the point we’re trying to make – we do have a couple of photograph albums. There is a sense that the photograph doesn’t lie. However, the photographs would either be staged or created for a purpose. I have a feeling that some of those photographs may not even be ones taken by the explorers themselves. So the photographic records here are not the product of the person compiling the album going out with their camera and snapping what they want to see and record. [32]

You might say the photograph itself is a true depiction of what is actually being photographed. But is it a true depiction of what they saw? Isn’t that the matter? [33]

And did you find a correlation between the image and the text and the diaries? [34]

Unfortunately, with some of the photographs we don’t have the written text to go with them. But we do feel it’s slightly staged, slightly stiff and sort of formal. The picture is almost presented to you to take away, rather than necessarily the full picture or the full experience that would be gained in travelling to those places. So the memory brought from that place would be slightly unreliable or not the full picture, shall we say. [35]

We tried to raise issues of reliability but also how people might consciously be trying to edit or present things. If you are sitting around scribbling something for your own benefit, that is one thing. If you are actually producing something you think you might show other people then it is slightly different… [36]

…and probably personality affected it as well. [37]

Absolutely. [38]

You have written in the catalogue about the young person who fought in a war and that he was very emotional in his writing. And about the chaplain, Reverend Adler, who would write short, dry notices in his diary. Obviously the emotion that permeates the young man’s writings comes partly because of the situation he was in and partly because it was his way of dealing with the war. However it makes me wonder, how would being in a war situation affect the reverend’s style of writing. Would he still write short and dry notes or would he open up and become emotional too? [39]

Yes, there is the element of personality there but I think there is also the element that the lad was writing to his parents, so it was more personal. He could let his feelings show in a way that the diaries of Reverend Adler, who was an army chaplain, could not. Adler’s diary, we think, may possibly have had an official function. Perhaps he felt it was not appropriate to be writing in a personal fashion. It’s that cliché of ‘stiff upper lip’. I think he probably felt terribly the awful things that were going on but he just didn’t feel it was appropriate to write about it in that context. But even this very crisp, concise…I feel 10% was visible and 90% was subtext to every little word that he used. So I think that in his own way he felt these awful things that were going on, but that it was not the context in which to write all that. Those sorts of things dictate how formal or non-formal things are, and how things would be presented… [40]

25 September 2009.

Text © Natalie Dekel and Karen Robson. Image © Southampton University.

Interview held in Southampton University, UK, 20 January 2009.

- Reading with Natalie, book here...

- Reading with Natalie, book here...