Awakening perception: Colin Wilson interviewed by Gregory Vincent St. Thomasino

6 September 2023 – Vol 1, Issue 1.

Colin Wilson: Faculty X does not make for symbols. It is simply that feeling of wide-awakeness that you get on a spring morning, and Rupert Brooke is full of it. It is important to grasp that the mind can deliberately change the way it sees things. Brooke tells how he can wander about a village wild with exhilaration. “And it’s not only beauty and beautiful things. In a flicker of sunlight on a blank wall, or a reach of muddy pavement, or smoke from an engine at night, there’s a sudden significance and importance and inspiration that makes the breath stop with a gulp of certainty and happiness. It’s not that the wall or the smoke seem important for anything or suddenly reveal any general statement, or are suddenly seen to be good or beautiful in themselves—only that for you they’re perfect and unique. It’s like being in love with a person. … I suppose my occupation is being in love with the universe.”

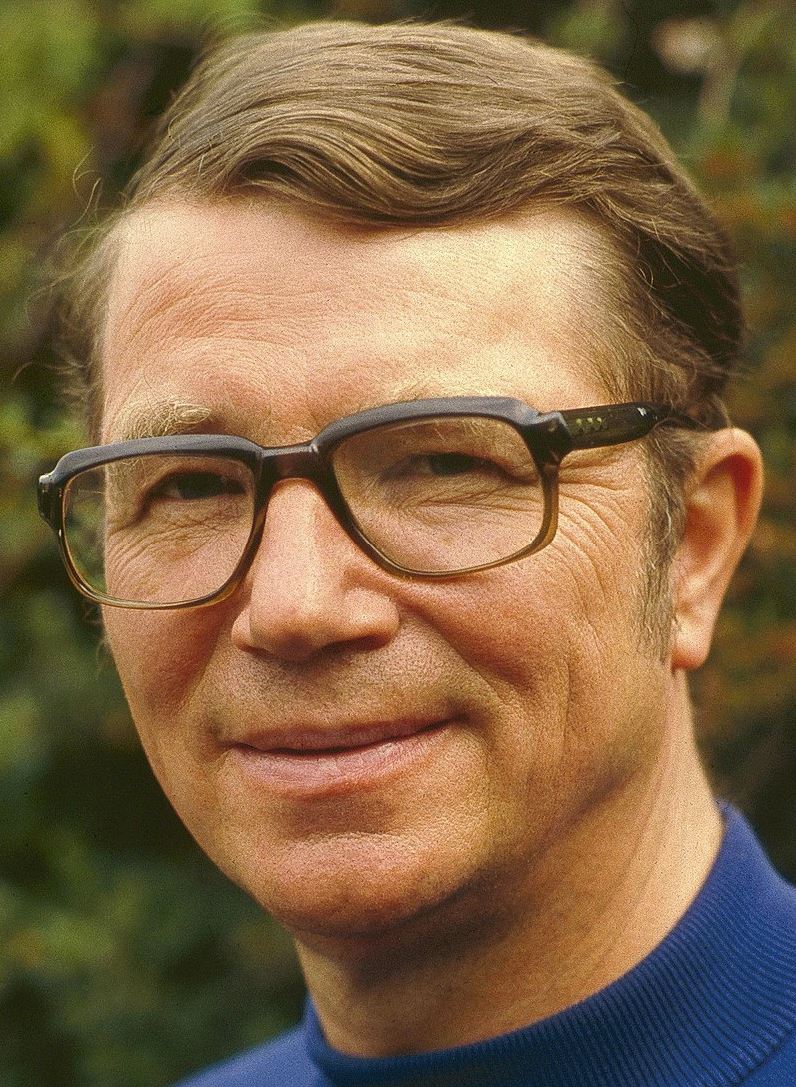

Colin Wilson, Goran Haven, Cornwall, 1984. Photo: Tom Ordelman, via Wikipedia. Creative Commons.

You can see that this has more to do with Gurdjieff’s “self-remembering” – that simultaneous awareness of looking at something and being aware of yourself looking at it – than with Arnold Toynbee’s experience in Mistra.

GVST: Still with Faculty X or the experience – so-called “peak experience,” or, what you have termed “promotion” – is poetry the result of this?

Colin Wilson: It seems to me that you over-emphasise Faculty X, which is essentially a trick of the brain. What is far more significant is what Chesterton calls “absurd good news,” and Proust “moments bienheureux”. It is true that what Proust experienced as he tasted the Madeleine dipped in tea was Faculty X, but what matters is his comment “I had ceased to feel accidental, mediocre, mortal.” The question is this: Is that true or an illusion? I would answer: True. So, what prevents us from grasping it? Our own tendency to what William James calls “a certain blindness in human beings,” what I have called “the bullfighter’s cape” that confines our perception to CLOSE-UPNESS. (The matador defeats the bull by not allowing it a clear view.) Close-upness deprives us of meaning.

You don’t need symbols. Yeats says it with great clarity in “Under Ben Bulben,” in quite clear and straightforward language. Shaw also said it quite clearly, and he is not a poet. In Back to Methuselah he defines the problem as “discouragement.” Blake calls it “doubt,” and said “If the sun and moon should doubt / They’d immediately go out.”

The people who deserve blame are the pessimists, the poisoners of our cultural wellsprings, like Samuel Beckett and William Golding.

Idiots parrot “Beckett is a great writer.” He isn’t. With the exception of Godot, which justifies itself by being funny, he is a dreary bad. And in encouraging the notion that life is “a tale told by an idiot,” and that our attitude towards it ought to be one of weary resignation, he is an enemy of human evolution. Other writers have taken the same attitude, including Shakespeare, but there is a greatness in his language that contradicts his negativeness. In Beckett’s later work there is no such counterbalance.

GVST: In your book, Poetry and Mysticism, in the chapter on Rupert Brooke, you say that “to experience ‘promotion’ is the mark of a poet.”

Colin Wilson: The promotion experience is, like Proust’s “ceasing to feel mediocre, accidental, mortal,” A GLIMPSE OF WHO YOU REALLY ARE, which is why Nietzsche can talk about “how one becomes what one is.” Cyril Connolly once said that inside every fat man there is a thin man struggling to get out. Well, inside every weak, modest man there is a Zarathustra trying to get out. That Zarathustra is the poet.

GVST: Given the state of philosophy, literature, politics and religions today (in 2006) – are you still optimistic?

Colin Wilson: Of course I am, because my optimism is a general basic verdict on human existence, as the pessimism of Beckett or Celine or Andreyev is their own assessment, and it seems to me to be full of their personal weakness and subjectivity – their poor emotional health, if you like.

In The Outsider my starting point was all those 19th century writers and artists who came to a sad end, and who ended by saying (in the words of a friend of mine) “The answer to life is no.” My reaction was like that of an accountant who is reacting to the statement “We had better declare bankruptcy.” “No, no, no. You’ve plenty of better alternatives.”

GVST: In your book The Occult, in the chapter entitled, “The Poet as Occultist” you talk about the powers within poets.

Colin Wilson: In that chapter, I was asserting that poets and artists have a naturally wider range of powers – second sight, telepathy, glimpses of the future – than non-poets. In fact, all men have wider powers than they realise, and underestimate them because of the human tendency to self-mistrust, the “fallacy of insignificance,” which I have been fighting all my life. If my “message” was clearly understood, it would be “You are stronger than you think.”

GVST: In your book Poetry and Mysticism You write (on page 50): “Poetry makes us slow down”. The basic difference between poetry and prose is that prose seems in a hurry to get somewhere; it is either telling a story or pursuing an argument. But when you read a poem you automatically slow your mind down to a walk knowing that it can only produce its effect if the mind is relaxed.

Colin Wilson: I said it most simply in telling the story of the Master Ikkyu, who was asked by a workman to write something on his tablet, and wrote, “Attention.” Disappointed, the man said, “Can’t you say something more?” And Ikkyu wrote, “Attention. Attention.” “But what does attention mean,” asked the bewildered workman. “Attention means attention,” said Ikkyu.

For years I pursued my investigation into the question of the peak experience and how it comes about. And then, towards the end of 1979, I had a major breakthrough. This is how I describe it in a book called The Devil’s Party: “On New Year’s Day, 1979, I was trapped by snow in a remote Devon farmhouse, where I had gone to lecture to extra-mural students. After 24 hours we decided we had to make an effort to escape. It so happened that my car was the only one that would climb the slope out of the farmyard. After several hours’ hard work with shovels, we finally reached the main road. The snow on the narrow country road had been churned up by traffic, but was still treacherous. And in places where the snow was still untouched, it was hard to see where the road ended and the ditch began. So as I began to make my way home, I was forced to drive with total, obsessive attention. Finally back on the main Exeter road, where I was able to relax, I noticed that everything I looked at seemed curiously real and interesting. The hours of concentrated attention had somehow ‘fixed’ my consciousness in a higher state of alertness. There was also an immense feeling of optimism, a conviction that most of our problems are due to vagueness, slackness, inattention, and that they are all perfectly easy to overcome with determined effort. This state lasted throughout the rest of the drive home. Even now, merely thinking about the experience is enough to bring back the insight and renew the certainty.”

This experience of a “more powerful” consciousness seemed a revelation, because it was not some sudden mystical flash; I had done it myself. So, surely it is possible to do it again.

I found it far more difficult than I had anticipated. I often tried it when driving, and achieved it briefly, but never for long. I did, in fact, succeed on one long train journey. But when I tried again the next day, on the return journey, I found it impossible. Obviously, the effort had exhausted some inner energy. I began to suspect that it was the sense of emergency that had brought about my first success, and that this was difficult to create at will. But over the years I have gone on trying. And finally, about two years ago, I found I was succeeding in learning the “trick” that would achieve the kind of focused attention required to release this sense of access to some kind of brain-energy. This focused attention brings with it an insight: that one of the main problems with the quest for insight is our tendency to what might be called “negative feedback.”

__

A longer version of this interview was first published in Eratio, 2006.

Colin Wilson was an English writer and novelist, known mainly for his books The Outsider (1956) and The Occult: A History (1971).

Gregory Vincent St. Thomasino is the founding editor at Eratio.