Beauty in ancient Egypt and China: a comparative analysis.

6 September 2023 – Vol 1, Issue 1.

Abstract

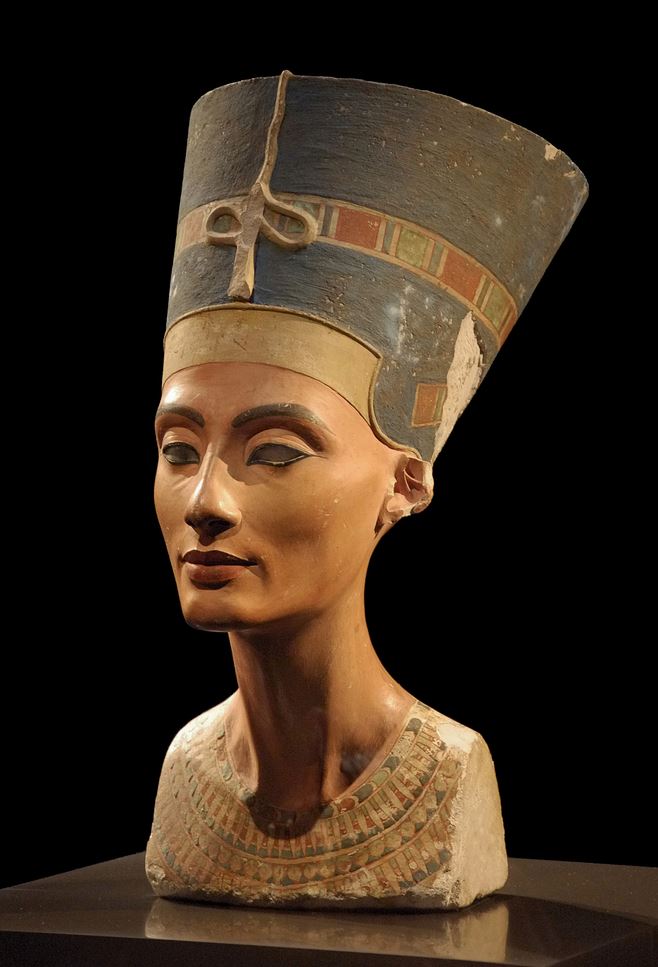

The standards of beauty vary greatly between societies and cultures, hence it is easier to find differences between concepts of beauty than finding similarities. However, it is not impossible to find connections. This article compares the theme of beauty in Ancient Egypt with Ancient China; two civilizations where beauty was revered, although with differing standards and expressions, and for different purposes. I will concentrate on Nefertiti (Egypt) and the goddess Luoshen (China).

Introduction

In both Egypt and China beauty was celebrated and worshipped for its expression of divinity. Ancient Egyptian beauty is represented by the perfectly symmetrical features of the statue of Nefertiti, characterized by its bold and pronounced lines. In ancient China, women’s beauty was eternalized in poetry and paintings created in the 5th century, depicting Luoshen, the goddess of the river, with a delicate and pale skin appearance. Both societies recognized the significance of beauty as a conduit to the divine and as a channel between the physical and spiritual realms.

Symbolism and spiritual significance

The concept of beauty is often shaped by physical attributes that are considered ideal. Nefertiti’s bust portrays a perfect idealized symmetry, with brownish-pink skin tones and brownish-red lips that were emblematic of vitality and health.

Nefertiti bust, 18th Dynasty, ca. 1351–1334 BC. Height: 49 cm, width: 24.5 cm, depth: 35 cm. Material: limestone, painted stucco, quartz, wax. Date found: 6 December 1912. Egyptian Museum and Papyrus Collection, Neues Museum, Berlin. Photo: Philip Pikart, via Wikipedia. Creative Commons.

Beyond the physical representation, Nefertiti was adornment with a floral collar that hints at the use of accessories and ornaments in her time. However, this representation of beauty seems to transcend the physical realm. Accessories and makeup were an integral component of beauty, yet not just for its appearances but rather for a spiritual purpose as well. Kohl, the ancient eye cosmetic, was not only used to enhance one’s features but also believed to provide protection against bad spirits. Beauty held the ability to ward off evil (Black, 2021).

China’s goddess, Luoshen, has features that differ greatly from Nefertiti’s. Luoshen’s slender figure and fair, pale skin were seen as harmonious representations of nature which was revered in Chinese culture. At times she was portrayed not as a goddess but as a nymph (Larrivé-Bass, 2015: 122; Theobald, 2012), an entity that is related directly to nature. Her beauty, free from the embellishments of makeup, was closely aligned with the natural world, in an unaltered pure form of physical perfection. Luoshen was celebrated not for her adorned appearance, but for her unspoiled grace that harmonized with the celestial and earthly realms. Indeed, the Chinese believed that the Luo River originated from the sky, cascading with grace to earth.

This is a 13th-century copy of the original, showing a detail (the last part of the painting) of ‘Luoshenfu’ (originally by Gu Kaizhi, 348-409). The Palace Museum, Beijing, China. Photo: Wikipedia. Creative Commons.

While Nefertiti’s bust symbolized power and youth that enable a connection to the divine, Luoshen’s connection to the divine is portrayed as a harmonious link between people and nature. Both civilizations, in their own ways, acknowledged that beauty embodied goodness’ perfection, alluding to the sublime.

A modern interpretation of Luoshen. ‘Luoshen, Goddess of the River’, by Gil Dekel and AI, 2023.

Society

Ancient Egypt fostered a society where beauty was not only an attribute but an indicator of status. Nefertiti’s beauty was seen as a testament to her role in the court, and to a divine favour as the queen and consort of Pharaoh.

Royalty and beauty were linked, with queens and kings serving as exemplars of aesthetic perfection, thereby commanding both authority and power. Beauty was believed to have the power of safeguarding against bad forces, hence Nefertiti’s beauty gave her the power to protect her people. This concept was used to gain loyalty and obedience among her subjects.

Beauty also played a pivotal role in religious practices, used to solidify authority and command loyalty. Royalties’ tombs were adorned with religious texts and artefacts of beauty. Beauty served as a bridge to the gods, a channel through which gratitude and worship were expressed. In pursuit of eternity, ancient Egyptians decorated their surroundings and their mortal remains with beautiful items, believing that this would help them transcend into the afterlife. At the same time, this was done to represent the mortality of the dead kings, allowing their legacy to continue so that their courts could continue to reign. For that purpose, the concept of youth beauty, representing health and vitality, was exaggerated. In wall paintings, women have been depicted as young, even if they were mothers of kings (Watterson, 2012).

The beauty of Luoshen, on the other hand, drew from a purity untouched by cosmetics or embellishments. This adherence to natural grace was based on a Daoist poem (Britannica, n.d.) and Chinese philosophy, suggesting that beauty was grounded in the balance between the human realm and the divine. Beauty, for the Chinese, was not merely a reflection of the self but a reflection of the cosmos – when an individual embodied beauty, they aligned themselves with the divine order of the universe. Beauty served as a bridge between the earthly and heavenly realms, helping people to connect with the divine through harmonious aesthetics. According to the philosophy, beauty found in nature was a glimpse of the divine’s presence on earth; a divine characteristic that was reincarnated in the goddesses (Meng, 2016).

Environment

Nefertiti’s beauty lies in the calculated symmetry of her features, the bold lines, and her famous crown that is tall, straight-edged and flat at the top (Abram, 2007: 10). Nefertiti’s bust can be seen as a mini monumental structure in itself, representing Egypt’s architecture. The lines that define her face and her iconic crown echo the bold lines of Egypt’s constructions. The calculated symmetry of her features parallels the precision and harmony that the ancient architects aimed to achieve. The architecture of Egypt was monumental, with temples, pyramids and pharaohs tombs, that showcased grandeur. In a way, Nefertiti’s bust is a visual microcosm of Egypt. Her beauty lies in being a nano-representation of the world around her. The structures of the world are projected through her beauty.

In contrast, Luoshen beauty lies in her flowing lines that emulate the natural world, and attempt to transcend human forms. Usually, she holds a fan or a lotus flower (Huixin, 2023). Confucianism and Daoism emphasize a harmonious relationship between humanity and nature. This is manifested in the integration of natural landscapes into architectural designs. Chinese gardens, for example, were aesthetic spaces and also harmonious microcosms of the larger natural world. Unlike Egypt’s human intervention in creating monuments, the Chinese intervention was in arranging, but not re-creating, elements from nature. Rocks, water features, and plants were harmoniously curated to evoke serene garden spaces.

Luoshen’s depiction presents this symbiotic relationship between humanity and the natural world. The painting portrays her in an idyllic retreat, a microcosmic garden where she becomes one with her surroundings. She becomes part of the world around her. Her beauty enhances the natural world, and is projected through the world.

Conclusion

The Nefertiti bust personifies perfection, but also status, lineage, and divine favour that reinforce authority and obedience. Chinese beauty, in contrast, was aligned with philosophical notions of cosmic harmony as a reflection of a broader universe, a means to harmonize the earthly and heavenly realms.

Despite their distinct interpretations, both cultures recognised beauty as a transformative power capable to transcend the material and evoke the spiritual. Beyond the realms of physical attributes and aesthetics, beauty was seen as a conduit through which people could connect with the divine. The implication is that beauty’s ability to transcend the ordinary, makes it a form of language through which the human and the sublime could converse. This form of visual poetry invokes both the tangible and the intangible.

With thanks to Gil Dekel for his support in the editing process.

References

Abram, Mary. (2007). “The Power Behind the Crown: Messages Worn by Three New Kingdom Egyptian Queens”. Studia Antiqua, Vol 5, No. 1. Accessed 30 August 2023, from: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/studiaantiqua/vol5/iss1/4

Black, Riley. (2021). Makeup in ancient Egypt. The University of Utah. Accessed 30 August 2023, from: https://attheu.utah.edu/facultystaff/makeup-in-ancient-egypt/

Britannica Encyclopaedia. (n.d.) “Gu Kaizhi”. Encyclopedia Britannica. Accessed 31 August 2023, from: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Gu-Kaizhi.

Huixin, Wu. (2023). Beyond beauty: Porcelain exhibition delves into the lives of ancient Chinese women. Shine. Accessed 31 August 2023, from: https://www.shine.cn/feature/art-culture/2303107125

Larrivé-Bass, Sandrine. (2015). Embodied Materials: The Emergence of Figural Imagery in Prehistoric China. [PhD Thesis]. Columbia University. Accessed 31 August 2023, from: https://academiccommons.columbia.edu/doi/10.7916/D83J3C8R

Meng, Chunhui. (2016). Redefining Nymph of the Luo River: A Practice-based investigation into a feminist reinterpretation of a traditional Chinese painting through the creation of animations. [MPhil Thesis]. Royal College of Arts. Accessed 30 August 2023, from: https://researchonline.rca.ac.uk/2204/

Theobald, Ulrich. (2012). Luo Shen, the Goddess of the River Luo. Accessed 30 August 2023, from: http://www.chinaknowledge.de/History/Myth/personsluoshen.html

Watterson, Barbara. (2012). Women in ancient Egypt. Amberly publishing: Gloucestershire.

About the author

Rana Fleihan is an academic writer, author and teacher, with an MA in English Language from Saint Joseph University, India. Her work is centred around enhancing learning opportunities for underserved populations across the Middle East. Her current interests are ancient civilizations and poetry. She is based in Lebanon.