Increasing creativity and accessing inner knowledge: the ‘Draw Your Breath’ method

14 February 2024 – Vol 2, Issue 2.

People often find it hard to be creative and to come up with innovative ideas or solutions. Since there are so many distractions in our society, from visual ‘pollution’ to “… fragmented attention …” (Newport, 2016), people struggle to connect to their inner creative space where pragmatic intuitive knowledge resides. The ‘Draw Your Breath’ method offers a solution. The method uses guided meditation and a simple art activity, to connect people to an inner creative and authentic space.

These days, individual creativity is more important than before. While so-called Artificial Intelligence platforms are doing much of the ‘thinking’ for us, it is crucial that we reclaim our ability to think, formulate ideas, and be original. What makes us humans is creativity, which is the power that combines thinking with emotions.

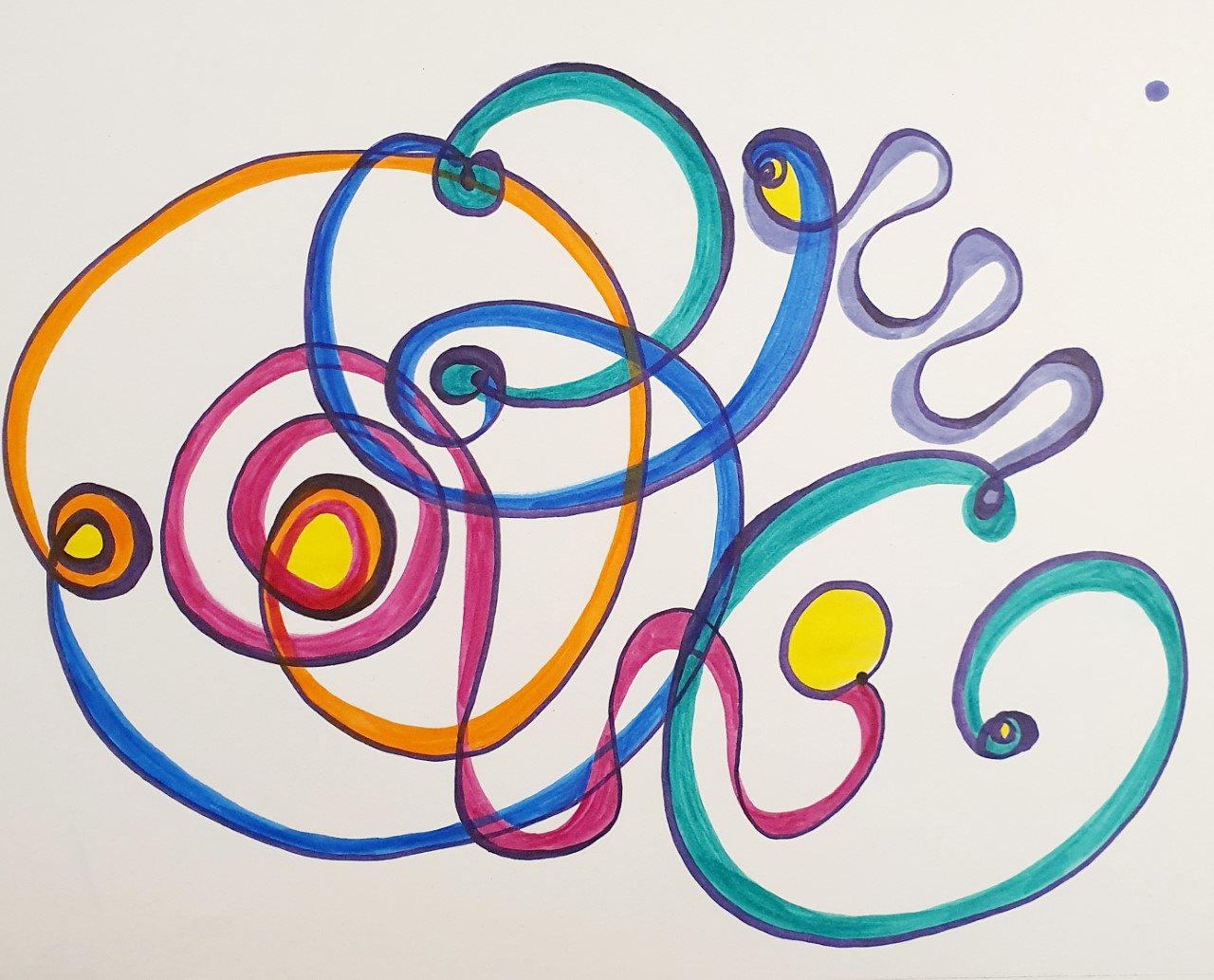

In a short art session, participants are asked to trace their breathing pattern on a piece of paper while they are still in meditation (see video/worksheet below). This process is unique in three ways.

First, the method differs from other guided meditations. Other meditations tend to ask participants to create art as an afterthought: the meditation ends, participants open their eyes and then discuss the experience. The ‘Draw Your Breath’ method does not operate in the afterthought zone, but rather in the meditative zone. The method engages participants whilst they are still in the meditation, in the relaxed phase, asking them to draw their breathing patterns. This offers a real-time, immediate channel for creativity to unfold, allowing for a seamless collaboration between the mindful state and the act of creative expression. The intuitive flow is synchronised with the hand moving on the paper.

A participant’s drawing, 2020. Usually, participants would only draw lines using a black marker, but they may also choose to colour their work, as seen in this example. Photo: Gil Dekel.

Secondly, breathing is a very individual activity (Dewey, 1933: 3). Drawing on paper something so individual and internal helps participants sharpen their observation skills and ‘look inside’. The act of breathing also creates a flow of ‘in and out’, which can regulate our thinking and feelings. This helps participants focus on being receptive while ‘de-focusing’ from the ‘mind-chatter’ and judgement. As attention widens, a reflective path opens to observe inner nuances within. These nuances are where true personal creativity lies. The experience is not mere fantasy or a dream state, but rather a clear grasp of internal visions and goals.

Thirdly, the method combines breathing, drawing as well as observing. The observation is both internal (meditative) and external (critical – looking at the art on the paper). As such, the analytical mind is not removed, rather it is given a new ‘role’; the role of an observer, instead of an analyser or a judge of emotions. Rilke (1950: 25) calls the experience: “You sat there as if dissolved … you were like a vacant place”. A bond is created – a ‘marriage’ of equal partners – emotional instinct and inquisitive observing mind. To use T.S. Eliot’s (1970: 16) words: a ‘concentration without elimination’.

Within an academic context, this method can significantly help researchers since any research requires seeing the world “… beyond the ordinary” (Janesick, 2016: 5). Researchers, who may be ‘saturated’ with ideas from the literature, can access their inner authentic place of original thinking and come up with new contributions to knowledge, beyond the limits of the literature (Chick, 2013).

A participant’s drawing, 2021.

The method uses art activity since art helps to visualise things. It is far easier to absorb visuals than words. Images represent how things look like while words require interpretation as they are symbols/signs of other things. And if indeed “… imagination is the beginning of creation …” (Shaw, 1927: Act 1, p.9) then imagining and visualising inner experience through art can lead us back to ourselves.

Art expands people’s horizons (Massie, 2023). It empowers people to go beyond familiarities (Maslow, 1994: 78) and beyond their comfort zone, both of which tend to stifle creativity (Dekel, 2009). Outside the comfort zone, participants enter a space of inner, intuitive truth (Steiner, 1972: 30). Since the art on the paper externalises something which is otherwise hidden (breathing), the experience is akin to looking in a mirror, or at a self-portrait. As such, the method provides participants with a metacognitive tool that magnifies their internal conversation and experience.

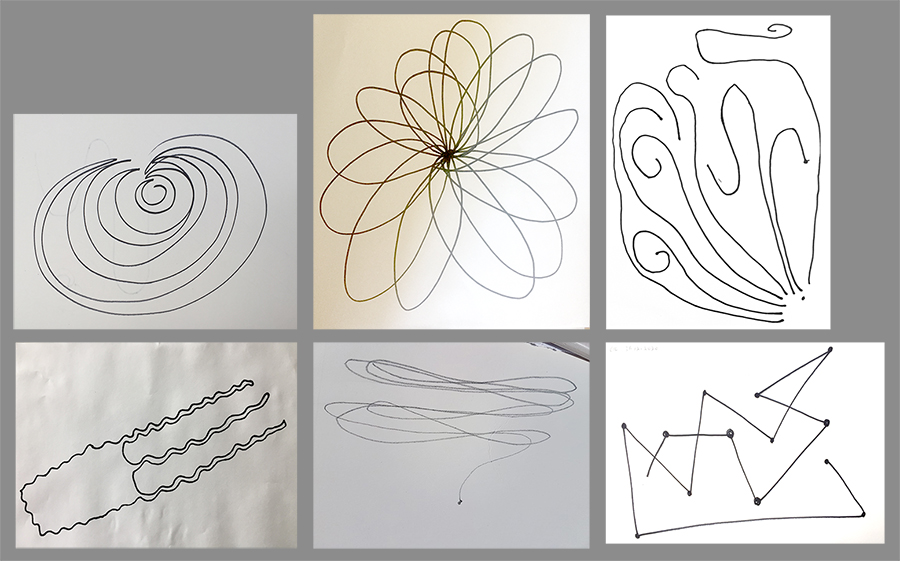

Six participants’ drawings (dates created: top row from left: Dec 2020, June 2021, Nov 2021; bottom row from left: June 2021, April 2021, Dec 2020.)

The process then moves from inner listening and observation to inquiry (Dekel, 2008). Participants look at their inner feelings/thoughts, which are visualised through the artwork, and reflect meaningfully. This inquiry is rooted in grounded theory where researchers start their exploration with inductive data based on experience, and only then do they analyse it (Charmaz, 2014: 1).

‘A Vacant Place’ by Gil Dekel and image-generating AI, 2024. This art was not created as part of a ‘Draw Your Breath’ session, but it is presented here as an illustration of the concept of meditation and imagination.

Participants take ownership of their drawings since it is they who drew the art; and the art reflects on their personal process, not on someone else’s process. As breathing is personal, there is no judgment involved. No one can judge the works and argue that a work is not ‘right’. Both personal judgment and judgment of other peoples’ works are removed.

Conclusion

The human personality is not linear, but complex. Likewise, reality is complex, with the internal and external worlds influencing our decisions. Sometimes “we sense others” (Mason, 2018: 7) better than we sense ourselves… It is therefore common for people to get confused as internal messages are tainted by external contradicting ones. These confusions stifle creativity and limit research advancements.

Using the ‘Draw Your Breath’ method can help participants clear their minds, and attune to their inner strengths and originalities. Walking safely outside the thick bricked ‘fortresses’ of comfort zones, the method helps participants see clearly. Once participants are allowed to see and think creatively, they can develop meaningful innovative works that can inspire others – and in the context of academia can gift the research community with cutting-edge research.

Worksheet:

The guided meditation video:

A4 piece of paper. Black marker.

Play the meditation video.

Towards the end of the drawing exercise, the facilitator asks participants to reflect on the questions below. Allow the answers (or feelings) to rise naturally – there is no need to force an answer, but only to lay the questions open. A few questions (some adapted from Tanner, 2017):

- What do I know about this topic?

- How could I best prepare to research it?

- How do I learn?

- Why is my research important?

- Where is my inspiration and guidance?

- What do I need to do? What is my goal?

- What do I feel, experience?

- What insights am I having?

- How do I best prepare for exams?

- Where am I going?

- Is this interesting to me?

- What is important here?

- Is change good?

- What strategies do I need to adopt?

- What would my ‘younger self’ say about this?

- If I did know what I want to do, how would I feel? What would I do? What would it look like?

You can also use the following keywords as they are abstract and open:

| combine | compose | design | compile |

| rearrange | construct | apply | construct |

| relate | rewrite | review | locate |

| translate | show | use | imagine |

| predict | relate | illustrate | select |

| categorise | connect | relate | arrange |

| define | describe | identify | know |

| label | list | name | outline |

| recall | recognise | reproduce | select |

| state | tell | show | |

| record | underline | collect |

> Download this worksheet as a Word document.

© Journal of Creativity and Inspiration.

Images copyright as specified.

Gil Dekel is a doctor in Art, Design and Media, specializing in processes of creativity and inspiration. He is a University lecturer, visionary artist, Reiki Master/Teacher, and co-author of the ‘Energy Book’. He was awarded the Queen Elizabeth II Platinum Jubilee Coin, in recognition of his dedication and commitment to pastoral work at Hampshire Constabulary.

References

Charmaz, Kathy. (2014) Constructing Grounded Theory. 2nd Edition. London: Sage.

Chick, Nancy. (2013) Metacognition. Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching. Accessed 12 April 2023, from: https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/metacognition

Dekel, Gil. (2008) Turning On the Light Without Choosing Which Way It Will Spread. Accessed 19 Feb 2023, from: https://www.poeticmind.co.uk/interviews-1/turning-on-the-light-without-choosing-which-way-it-will-spread. See paragraphs 12-24.

Dekel, Gil. (2009) Inspiration: a functional approach to creative practice [PhD thesis]. Accessed 11 February 2023, from: https://www.poeticmind.co.uk/research/phd-thesis/8-1-4-art-practice-as-a-research-method/

Dewey, John. (1933) How We Think; A restatement of the relation of reflective thinking to the educative process. Massachusetts: D.C. Heath and Company.

Janesick, Valerie J. (2016) ‘Stretching’ exercises for qualitative researchers. 4th edition. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Maslow, Abraham. (1994) Religions, Values, and Peak-Experience. New York: Penguin.

Mason, Jennifer. (2018) Affinities: Potent Connections in Personal Life. Polity Press: Cambridge.

Massie, Miranda. (2023) ‘The Jewish lawyer who left everything behind, and founded a climate Museum.’ Interview with Daniel Adelson for Ynet online, 22 April. In Hebrew. Accessed 22 April 2023, from https://www.ynet.co.il/environment-science/article/skricjkq3

Newport, Carl. (2016) Deep Work: Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted World. London: Piatkus.

Rilke, Rainer Maria. (1950) The Notebook of Malte Laurids Brigge. London: The Hogarth Press.

Shaw, Bernard. (1927) Back to Methuselah. New York, Brentano’s. Accessed 15 March 2023, from: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015030835154&view=1up&seq=123&q1=imagination%20is

Steiner, Rudolf. (1972) A Modern Art of Education: Fourteen lectures given in Ilkley, Yorkshire, 5th – 17th August 1923. London: Rudolf Steiner Press.

T.S. Eliot. (1970) Four Quartets. London: Faber.

Tanner, Kimberly D. (2017) ‘Promoting Student Metacognition.’ CBE – Life Sciences Education, Vol. 11, No. 2. The American Society for Cell Biology. Accessed 22 April 2023, from: https://www.lifescied.org/doi/full/10.1187/cbe.12-03-0033