Conceptual Blends as Spaces for creativity

5 July 2024 – Vol 2, Issue 3.

How does creativity work in our minds? In this article, I will explain how our minds creatively combine different ideas from various areas within Cognitive Linguistics to produce new and innovative concepts.

In the field of Cognitive Linguistics, several models offer different but interrelated ways in which the mind, via cognitive processes, gives rise to creative conceptual integration. Conceptual integration is a process where the mind combines different ideas from various domains, making them easier to understand and use. These ideas come from our experiences, knowledge, and the language we use daily. Speakers intend to convey complex, often creative, meanings using language and other modes of communication, and similarly they have to interpret what others say. In this paradigm, language and linguistic knowledge is abstract in nature, since language involves more than just words; it involves complex mental activities such as organising thoughts, making connections between different ideas, and drawing on personal experiences and knowledge.

Figure 1: ‘The networks of the mind’, by AI / Gil Dekel. 2024.

Conceptual Metaphor Theory (CMT)

In the process of conceptual integration speakers integrate different types of meaning into unified, conceptual wholes – mental representations. Using Mandušić’s (2024) example, when people talk about time in terms of money, as in ‘do not waste my time’, speakers are able to speak, and more consequentially, to think of time in terms of money. This phenomenon, theorized as Conceptual Metaphor Theory (CMT) (Lakoff, 1987), postulates that people can and often use conceptual mappings between domains to make sense of complex abstract and experiential (including social) phenomena. ‘Money’, is a socially-embedded, concrete domain. People map several of its properties onto the more abstract domain of ‘time’, providing it with structure and facilitating its comprehension, and thus giving rise to the Conceptual Metaphor ‘Time is Money’.

Conceptual Blending Theory (CBT)

There are a multitude of metaphors that help us articulate our understanding of reality (Goatly, 2007). Many of them are so frequently used and entrenched in our lives that we do not think about them as metaphorical. Some others stand out and feel more provocative, more creative. Conceptual Blending Theory (CBT) (Fauconnier and Turner, 2002) explains how these creative uses of language emerge through integrating multiple mental spaces (mental frameworks where ideas merge).

While CMT focuses on how we connect ideas from different areas, like “Time is Money,” to understand complex concepts, CBT focuses on how we blend multiple mental pictures together to form new, creative thoughts and scenarios.

There is substantial research on metaphor and creativity (e.g., Kövecses, 2010). Here I focus exclusively on the explanatory power of CBT due to its elaborated model of spaces, and how they can be instrumental in explaining creative processes. In a way, metaphors can be thought of as consolidated patterns of thought and language – regular, habitual patterns in our thoughts and language that we use consistently. Conceptual blends in this context can be thought of as creative uses of language which might then become entrenched and give rise to more established metaphorical patterns of language and thought (such as the thought “Socrates debating magic at Hogwarts School).

Mental spaces

Conceptual Blending Theory is, in contrast with Conceptual Metaphor Theory, a theory of online meaning construction. Online meaning construction is the real-time process of creating meaning as we engage in communication. Unlike pre-formed or static meanings, online meaning construction happens dynamically as we interact with language and contextual information, allowing for immediate interpretation and response to new information. As such it captures the fluid and inventive aspects of how we use language, and therefore it is especially suited to examine creative uses of language. Words fundamentally prompt the construction of mental spaces (Fauconnier and Turner, 1996). These can be defined as “small conceptual packets constructed as we think and talk, for purposes of local understanding and action. They are interconnected, and can be modified as thought and discourse unfold” (1996: 113). In other words, mental spaces are temporary, dynamic structures in our minds where we construct meaning during communication. They help us organize information, understand context, and integrate various elements as we think and talk. Mental spaces emerge and respond to speakers’ situational contexts, and accommodate for creative uses of language. Mental spaces are populated by different types of elements, such as objects, actions, entities, and processes invoked in linguistic uses (Hart, 2008).

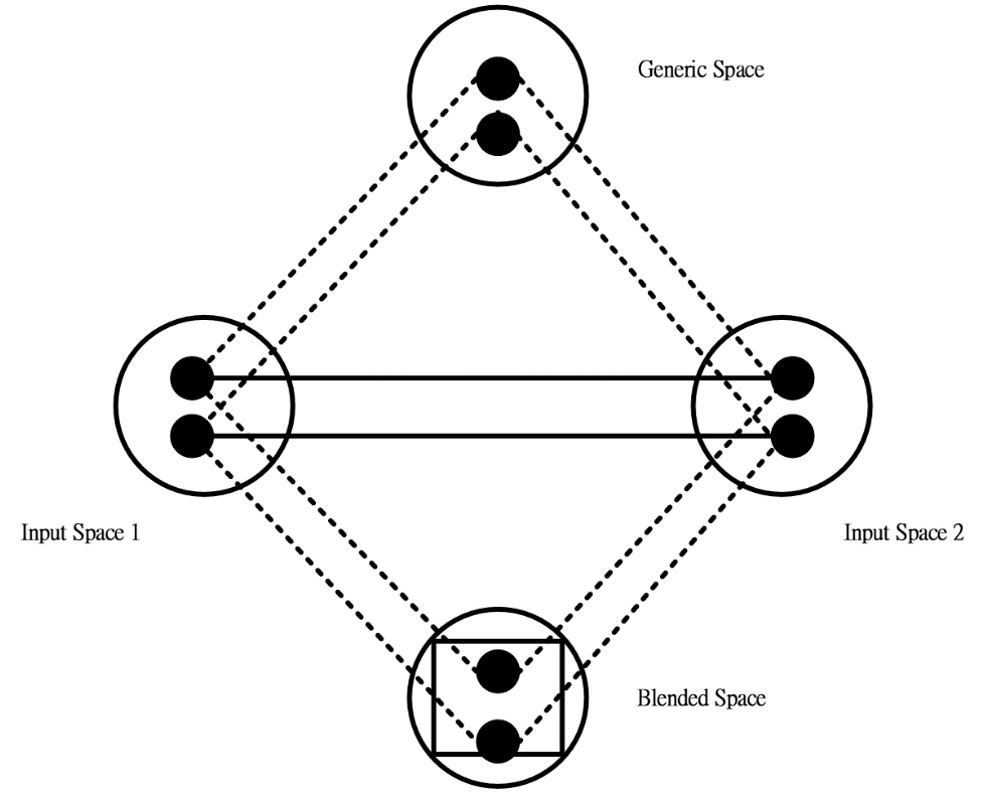

Figure 2: Conceptual Blending Network diagram (redrawn from Hart, 2008: 95).

According to CBT, conceptual blends emerge within networks of mental spaces. The fundamental blending network consists of four spaces (Figure 2): a Generic Space, two Input Spaces, and a Blended Space.

Metaphors like ‘Time is Money’ invoke spaces containing elements belonging to two different domains or scenarios, and as discourse unfolds, a space emerges for each scenario – Input Space1 and Input Space2, ‘Time’ and ‘Money’ in our example. Importantly, “[I]n conceptual integration, the two input spaces share counterpart connections between elements” (Hart, 2008: 96); these are represented in Figure 2 by solid lines. Conversely, the dashed lines inside the four spaces indicate conceptual projections within the network.

Additionally, the Generic Space hosts common elements in both Input Spaces which are abstract in nature – abstract roles, actions, relationships, or properties that can be found in both input spaces. This space gives abstract substance to the blending network (cf., Fauconnier & Turner, 2002). In the example of ‘Time is Money’, both share common elements: both are seen as valuable resources that can be used or managed. Both can be spent, saved, or wasted. Both can be Agents (initiators of action) and Objects (receivers of action) within different types of relationships.

Finally, The Blended Space receives structure and elements from the Input Spaces, and more importantly, it also has an emergent structure which is unique to the blend (Fauconnier & Turner, 2002), and so it can be said that this is where language enables creativity at a very fundamental level. This structure is symbolized by the solid square in Figure 2. Three blending processes are involved in the generation of the emergent structure: Composition, Completion, and Elaboration.

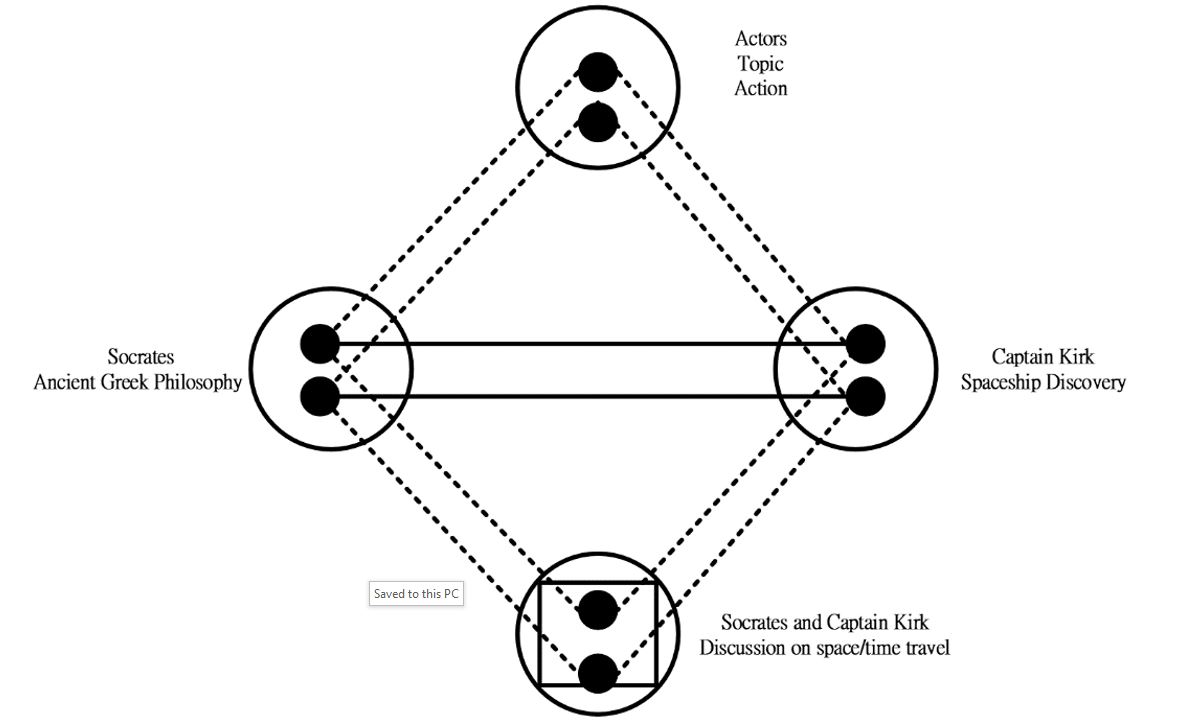

Let us consider an example: “Captain Kirk and Socrates discuss time-space travel aboard the Discovery.” This utterance can be examined briefly in relation to the blend it generates:

- Input Space1: Captain Kirk and the Star Trek universe (including the spaceship Discovery).

- Input Space2: Socrates and Ancient Greece.

- Generic Space: the abstraction of elements from both Input Spaces which underlie the interaction of the utterance (actors, action, topic, location, etc.).

- Blended Space: where both Input Spaces blend to allow the speaker to generate a situation or event which is purely creative (imagining a conversation between Captain Kirk and Socrates about the principles of time-space travel aboard the spaceship Discovery.)

In a nutshell, in the theoretical framework of CBT, language use underpins creativity at a conceptual level. Language builds mental spaces for real-time processing, where different spaces interact in the mind generating complex mental representations. The Blended Space is where properties, elements and entities from other mental spaces are projected to and, more importantly, make up a unique structure that emerges with its own inherent logic. This emergent structure is partially premised upon the Input Spaces, but is essentially creative in nature.

Composition, Completion and Elaboration

There are three blending processes involved in the generation of the emergent structure. Let us remember that speakers can use different modes in communication, including language, images, music, gestures, and more (Bateman, 2014), and instances of those can build mental spaces in speakers’ minds. The Blended Space can then inherit part of the elements included in those mental spaces. Thus, the Blended Space can be thought of as the ‘mental pocket’ where several types of meaning come together, giving rise to creative and holistic outputs; in our example, a scenario where Socrates and Captain Kirk engage in conversation. Let us focus on the three blending processes which enable the generation of this emergent structure, the space for novelty and creativity. These processes are Composition, Completion and Elaboration (Fauconnier and Turner, 2002).

Composition (creating new connections) is the process through which the blending network enables new relations in the blended spaces – relations between elements that do not exist in the Input Spaces are composed in the Blended Space. In our example above, using composition: Socrates and Captain Kirk co-exist in the same time frame and location.

Completion (using background knowledge), on the other hand, is the operation where “relevant structure from background knowledge associated with the elements in the input spaces is recruited into the blend” (Hart, 2008: 97). This process is particularly important when it comes to creative uses of language because knowledge is not stored in isolation, but rather in complex structures in the mind. One such type of knowledge structure is a conceptual frame (Fillmore, 1982). Frames are conceptual, stable, and adaptive knowledge structures stored in long-term memory which serve as background for the activation of specific concepts. For instance, the concept ‘Monday’ as a day of the week, when used in utterances, necessarily activates the frame ‘week’, which serves as background information – we need the concept of ‘week’ to understand the concept of ‘Monday’. Similarly, when we think of ‘hand’, we necessarily activate the background concept ‘arm’ and also ‘body’. In our example above, the Star Trek universe can be said to serve as a complex frame, and so when referring to the spaceship ‘Discovery’ and ‘space-time travel’ selectively we establish a location for the conversation, and a topic for the conversation. This is a pragmatic phenomenon, where “speakers may choose to recruit particular structure in order to promote a certain perceived reality” (Hart, 2008: 97). In our take on Blending Theory, creativity can be understood as a pragmatic phenomenon, where blends are a function of what speakers’ choose to say and how what is said is interpreted.

Last, Elaboration (developing combined ideas) is the most important operation in the blending process as it is ‘the running of the blend’. In Elaboration, those elements within the Input Spaces connect and work together, combining in the emergent structure. Following the example above, through Elaboration is how Socrates and Captain Kirk become entities that are ‘real’ in the Blended Space, engaging in a world created by the mind, by means of linguistic input.

Figure 3: ‘Socrates and Captain Kirk aboard the Discovery’, by AI / Javier Mármol Queraltó. 2024.

In order to successfully run this blend in our minds, we can describe the process using a mental spaces approach within CBT. This process of examination, for creative writers, for instance, can help identify particular meanings to be communicated and considered. Let us scrutinize our example again: ‘Captain Kirk and Socrates discuss time-space travel aboard the Discovery.’

Mental spaces:

Let us consider the word ‘Socrates’, which generates several of the following elements, and which are potentially available in Input Space1:

- Socrates as a historical figure, the epitome of Greek philosophy.

- Ancient Greece (with specific information about this time period, such as historical events, cultural practices, and societal norms of that era).

- The body of philosophical knowledge attributed to Socrates.

- Any other information relevant to speakers within this context.

Similarly, we can contemplate the possibility that the expressions ‘Captain Kirk’, ‘aboard the Discovery’ and ‘time-space travel’ generate another mental space, Input Space2, including several of these elements:

- Captain Kirk is a character of a fictional world, the Star Trek universe;

- The Discovery is the spaceship commanded by Captain Kirk;

- Time-space travel is a reality in this fictional world;

- Any other information relevant to speakers within this context.

The Generic Space provides structure to the blending network, as it focuses on abstract roles, actions and other aspects:

- Socrates and Captain Kirk are Actors.

- The spaceship Discovery is the Location.

- The Action is one of ‘discuss’.

- Time-space travel is the Topic of the Action.

In short, when we engage in creative uses of language, we often create mental connections between different ideas or concepts. These connections can go beyond just language and involve various elements. For instance, a speaker might use non-verbal cues or context to evoke mental spaces (i.e. input spaces), which then blend together to form new meanings. A speaker may combine a gesture of drawing a heart shape in the air while saying ‘love’ to blend the concepts of love and its symbol. This process is subjective and allows for creative interpretations of linguistic phenomena.

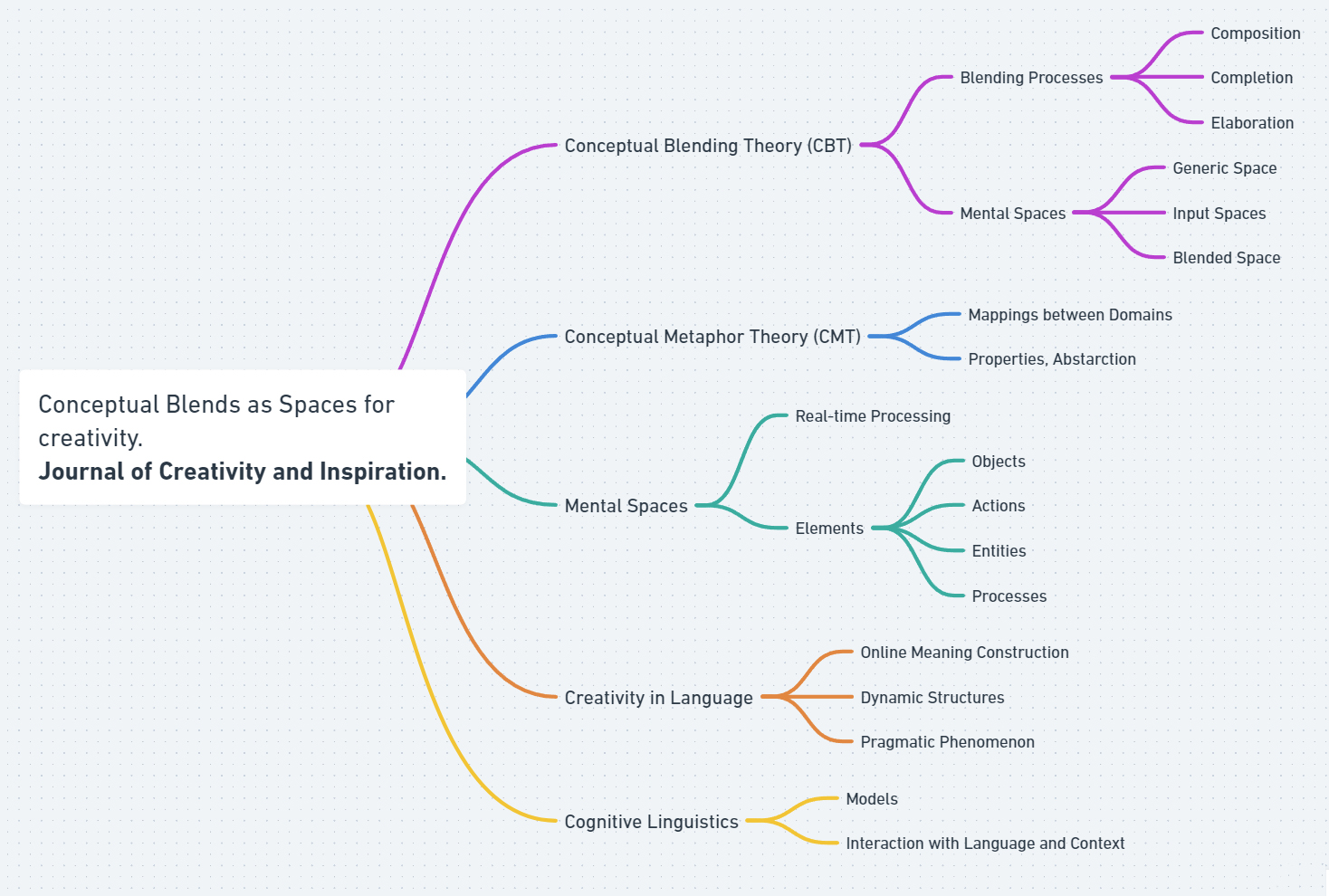

Figure 4: Conceptual Blending Network for ‘Captain Kirk and Socrates discuss time-space travel aboard the Discovery’ (adapted from Hart, 2008: 95).

The blend:

Within the Blended Space is where the emergent structure hosts creative uses and understandings of language use (and other modes of communication). The emergent structure inherits properties, relations, participants and actions from the other mental spaces, which it uses to run the blend in the Blended Space. Let us remember that the blend emerges as a function of the blending operations of Composition, Completion and Elaboration. Possible interpretations include:

- Socrates is alive.

- Socrates exists in a fictional world of Start Trek.

- Socrates and Captain Kirk engage in conversation.

- Socrates and Captain Kirk share a language or means of communication.

- Any other emerging knowledge stemming from the speakers’ situational context.

With this Conceptual Blending Network (Figure 4), speakers can engage meaningfully in creative uses of language. The Blend Space, with its new structure based on the blending processes outlined above, is a creative area where anything can potentially unfold. The Elaboration operation is the most significant here, mainly because it is one of integration in that seemingly implausible worlds, events, actions, actors and relationships are conceivable.

In sum, the field of Cognitive Linguistics provides several frameworks to better understand creative uses of language, as well as language in combination with other modes of communication. Conceptual Blending Theory is especially well-suited to explain creative uses of language. CBT is not necessarily restricted to language, as it is a theory of cognition, and it can be applied to other semiotic systems.

At a glance:

© Journal of Creativity and Inspiration.

Images: Figure 1 – AI / Gil Dekel. Figures 2-4 – AI / Javier Mármol Queraltó.

Javier Mármol Queraltó obtained his PhD in Linguistics from Lancaster University, where he researched Cognitive Linguistics, Critical Discourses and Multimodality. His research topics also include discourses of migration in the legacy media, Educational Technologies, and AI in Higher Education contexts. Javier is based at the University of Southampton, where he undertakes Learning Technologist duties.

References

Bateman, J. A. (2014) Text and Image: A Critical Introduction to the Visual/Verbal Divide. Routledge.

Fauconnier, G., & Turner, M. (1996) Blending as a central process of grammar. In E. Goldberg, A. (Ed.), Conceptual structure, discourse and language (pp. 113–130). Stanford, CA: Center for the Study of Language and Information (CSLI) Publications.

Fauconnier, G., & Turner, M. (2002) The Way We Think: Conceptual Blending and the Mind’s Hidden Complexities. Basic Books.

Fillmore, C. (1982) Frame semantics. In Linguistic Society of Korea (Ed.), Linguistics in The Morning Calm (pp. 111-137). Hanshin Publishing.

Goatly, A. (2007) Washing the Brain: Metaphor and Hidden Ideology. John Benjamins.

Hart, C. (2008) Critical discourse analysis and metaphor: Toward a theoretical framework. Critical Discourse Studies, 5(2), 91-106.

Kövecses, Z. (2010) A new look at metaphorical creativity in cognitive linguistics. Cognitive Linguistics, 21(4), 655-689.

Lakoff, G. (1987) Women, Fire, and Dangerous Things: What Categories Reveal About the Mind. Chicago University Press.

Mandušić, M. (2024) Conceptual Metaphor. Journal of Creativity and Inspiration, 2(2).