Interaction of shapes, tones, and colours: Stewart Beckett interviewed by Gil Dekel

5 July 2024 – Vol 2, Issue 3.

Gil: How do you consider your work; is it ‘abstract’ or ‘realistic’?

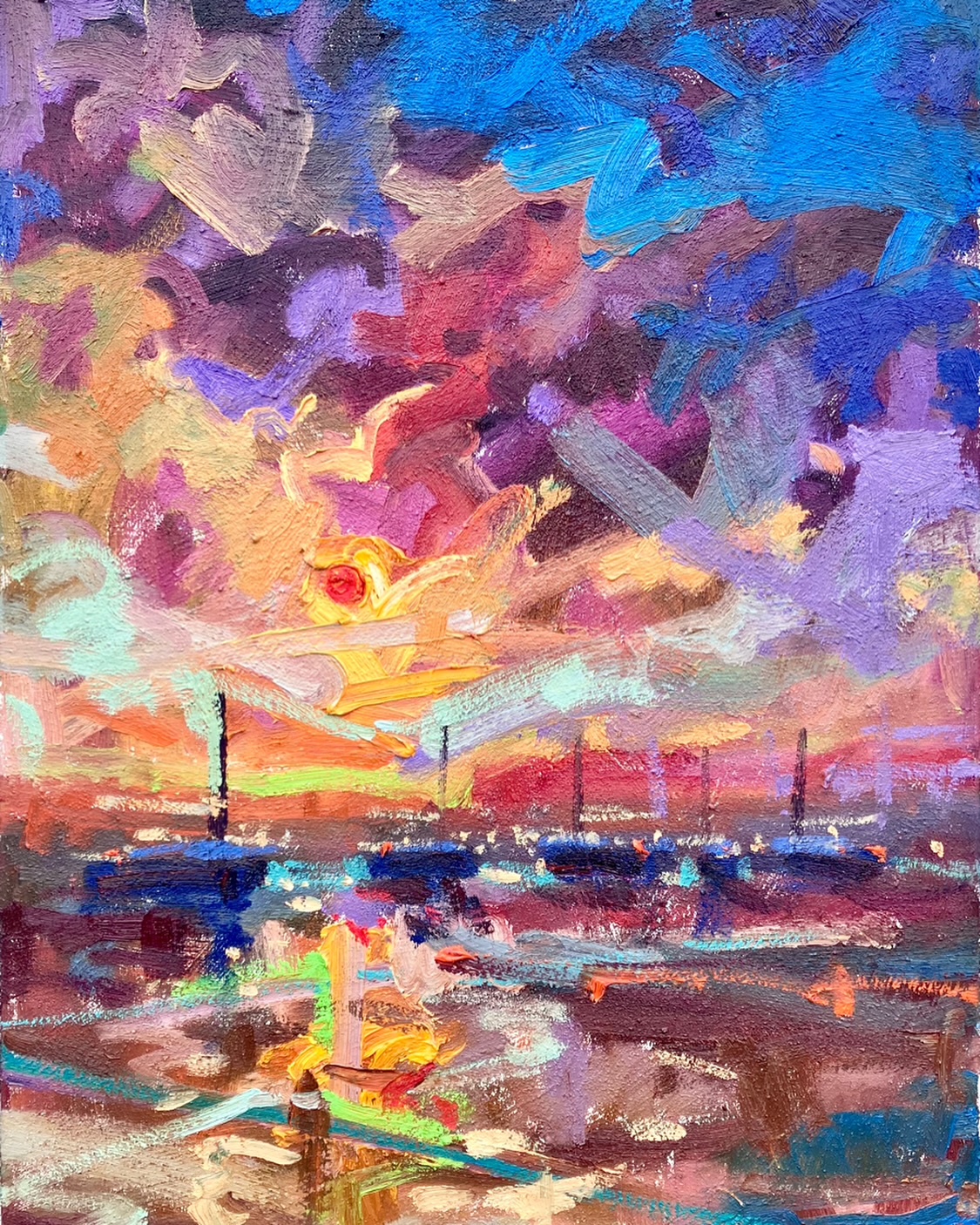

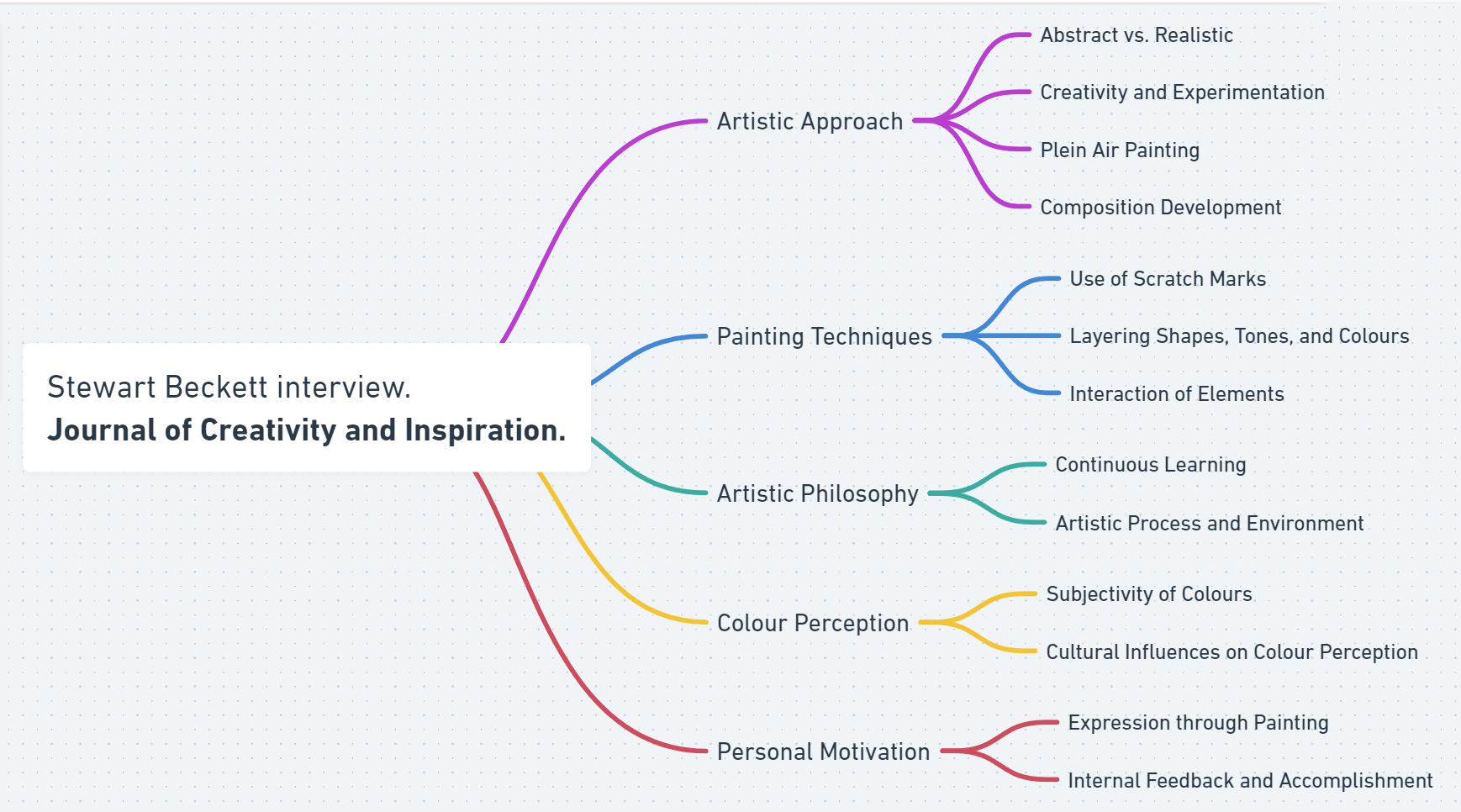

Stewart: Everything we see is abstract in a way… it’s just a construct of our brain. I see all my paintings as abstracts; it’s just that some are more recognisable than others… So, a lot of my paintings often come out of periods where I’ve been doing portraiture or figurative work. That kind of work is quite intensive in terms of drawing or being precise, putting a lot of effort into the technical aspects. Sometimes, after doing that, I like to create these types of pieces – the ‘abstract’ ones – because it almost reinvigorates my creativity, like a refreshment for my brain, allowing me to play and experiment. So, is it abstract? Yes and no… In the painting below, you can see very scratchy marks. That came about purely by accident when I took a knife blade and started scratching at the surface. I liked the effect it gave. It was just something I thought would be interesting, adding another layer to the surface.

‘Sun in pink 1’, oil on canvas, 18’ x 24’. 2023.

You could view this work as a landscape, but equally, you could view it just from the marks. If you zoom in, it’s purely abstract. There is no detail, just blocks of colour and indications of things, not specific things. I quite like that. In terms of landscape work, that’s better for the viewer because it allows for more imagination. It gives the viewer a bit more freedom to make their own mind about it. In the same way that you were asking if it’s abstract or not; that question poses itself in your mind, and hopefully, other people will have questions as well.

People do not operate like cameras. We don’t build an image from an outline and just colour it in. My process is more about seeing shapes, tones, and colours and then, like a jigsaw puzzle, layering them and piecing them together over time to create an aesthetically pleasing design or, if it’s a subject-oriented piece, something that carries the subject through.

‘Memory 1.0’, oil on canvas, 18’ x 26’. 2024.

Gil: So, how do you see the reality around you; do you notice the elements, colours, shapes, or do you see a subject?

Stewart: That’s a very good question. I do a lot of plein air painting which involves going out into the landscape and trying to find a pleasing subject or a good candidate for a piece of work. It can be quite difficult to narrow down nature into a specific size of canvas, into a 16 by 10 or 10 by 5. So, there’s a big element of abstraction and simplification involved because the complexity of our vision picks up so much detail, but that doesn’t make a good painting. It’s about reducing that information and making something of it.

When I’m out, I use experience, guesswork, and experimentation. If it fails, it fails. I’m not afraid of failing because not everything you do is going to work. I think that’s a big part of it as well. The fact that you do it and learn from it is more important than the actual result. Often, the product doesn’t represent what you get out of it as the artist. In the final work, you’re only seeing a small part of the effort that went into that piece of work. Many paintings get rejected, painted over, or recycled. But that’s part of being an artist. Potters do it, writers do it – everyone who is creative does it because it’s part of the process.

‘Is it lilies’, oil and acrylic on canvas, 18’ x 26’. 2021.

Gil: How do you feel about the use of AI in art?

Stewart: I think it’s not a bad thing and could be good for artists. AI is designed to replicate to the best of its ability, but it negates those happy accidents and the human element of creativity. AI might learn to imitate some elements, but whether it would truly have a soul, I don’t know. From a personal perspective, I think it will enhance authentic work. Any work that is imitative or purely commercial might face a backlash. But if you’re an artist, ‘in it for the long haul’, and looking to learn more about yourself and the human condition, then that is something that the audience will look for. I don’t think we need to worry about AI.

‘Sun in pink II’, oil on canvas, 16’ x 20’. 2023.

Gil: We mentioned the scratches in some of your work. They seem to hold quite different energy, and movement, from the other elements in the painting.

Stewart: Yes. I’m quite interested in energy. I have a very long history of physical exercise and inner-being work, and I bring that into my painting to a large degree. It is how I connect to the work. Often, in a very sedentary sort of view like the work above, you wouldn’t expect to have very aggressive, energetic marks because they’re almost counter to the feeling of the scenery in the painting. But for me, the scratches add an interesting layer because it’s almost like you’re cutting through that very soft feeling to the underbelly of something different. Yes, it’s just showing layers of paint underneath, but it’s the action of the artist that comes through rather than it just being a painting. I really enjoy that and find it very invigorating.

‘Memory 2.0’, oil on canvas board, 18’ x 24’. 2024.

Gil: It is also about bringing art to life and then letting it have its own life.

Stewart: Absolutely. There are a couple of paintings that I have an attachment to because they were landmarks in my learning. But generally, I don’t hold on to anything. It’s like the Buddhist sand paintings, where they spend hours making intricate art, but they do not hold to it, rather they wipe it away.

I always view my paintings as something I can recreate. I did a painting a while ago, and I decided to create another one. Of course, the experience is different the second time, as it’s just a duplication in a sense. You could argue that you’re only duplicating the scene in the painting. The filter it goes through depends on the environment – whether the painting is created on-site or in the studio, which has different effects. The energy and atmosphere influence the work, which you can’t easily replicate back in the studio. So, I wouldn’t take a piece that I started outside and try to finish it in the studio. I’d rather start a new one in the studio, bearing in mind what I felt when I did the original.

‘Illusion of trees’, acrylic and oil on canvas, 20’ x 24’, 2021.

Gil: It sounds similar to the process of writing a poem. It starts with the feeling, an experience.

Stewart: Yeah, for sure. Particularly when you’re out, the conditions play a massive part in the product. You’ve got the sun, the wind, rain, flies, people talking to you, dogs – every kind of distraction. In the studio, you’ve got none of that. You’ve got all the time in the world, lovely music, a comfy chair. It’s a different environment, so what you put into the painting is going to be totally different. I’ve done so much of it now, that I can almost recreate that outdoor feeling in my mind when I’m in the studio. But I still wouldn’t take an external piece and then try to finish it in the studio. I’d rather start a new one, bearing in mind what I felt when I did the original.

Gil: How do you start developing a composition?

Stewart: It actually depends on the light conditions, especially when you’re outside. Light is the guiding factor for most artists. It can change a scene dramatically, making it more, or less interesting. I don’t have preconceived ideas of what I want to paint. I look for the interaction of shapes, tones, and colours in an abstract sense. I focus on the general big shapes first and then the smaller shapes. It’s almost like shorthand in writing, trying to mimic nature without being too representational. It helps balance the composition, make it flow better, and keep the viewer engaged.

Gil: I think your paintings have no boundaries; the scene continues outside the frame.

Stewart: I always feel that the surface of the canvas is not actually the extremity of the piece; it’s just how much room you’ve got to work with… The more you can allow the viewer to go out of the painting and come back, the bigger it feels.

You might have lines that lead the viewer out of the frame, so you need other lines to pull the eye back, otherwise you lose the viewer. If you have too much going in one direction, then they don’t come back… The scratch marks that I create on the canvas might counter a strong line going in one direction. The marks are designed to pull the eye back in another direction. I think about that quite heavily when I’m working.

It’s almost like music. You’re trying to keep the melody but also create interesting notes here and there to keep the brain interested in the rhythm. You need evenness, but not too much, because if it’s too even, then it becomes too balanced and the viewer thinks, ‘Oh, I know what’s going on there’, and then they just leave. So, you want to put something unexpected in there, a little surprise.

‘Memory 3.0’, oil on canvas, 24’ x 30’. 2024.

Gil: The colours that you are using are quite distinct. Is that how you see them in nature?

Stewart: Colour is very tricky because we all see it slightly differently, depending on our emotions and other factors. Personally, the colours I use are influenced by various things. For one, pink in the West is seen as a very feminine colour. However, in Asia and the East, pink is seen as quite masculine. That interplay, where just a colour can have quite a bias in its influence, really intrigues me.

Colour is subjective. When you look at a sunset or a landscape directly, you don’t see all the colours. You have to not look at it directly, letting the retina take in the colours. Like those puzzles where you have to de-focus, to blur your eyes to see the shapes. All colours are there in the scene, but when you look at it directly, it’s almost like quantum physics – they disappear because your brain filters out a lot to make sense of it. I am trying to discover colour and make it a bit more obvious, but also allow it to be as natural as possible without filtering it.

Gil: Why do you create art?…

Stewart: Painting is my form of expression. I’m not a sculptor, but I sculpt in paint. It’s my conversation with my surroundings. When you see something and feel inspired by it, the challenge is trying to create that with just mud, because that’s essentially what we’re dealing with – paint is pigment in oil. It’s a very simple, basic kind of technology. It’s magical when something works, ‘I did that’. It gives you a real sense of accomplishment.

That internal feedback is probably what keeps me going. It’s a double-edged sword in a way because it keeps you working harder to get better, but on the other side, sometimes you get moments of clarity where you think, ‘Yeah, I’ve actually got something there. I actually understand something. I’ve been able to achieve something’.

At a glance:

© Journal of Creativity and Inspiration.

Images/art © the artist.

Stewart Beckett is a visual artist and a painter. Since taking up a residency at the Arches studios in 2016 he has been researching painting and the effect it has on the practitioner. His subjects are varied but with a common focus on the way they are made. He has exhibited throughout the UK and has been included in the Royal Portrait Societies exhibition at the Mall Galleries, London (2019). He has been featured on Sky Arts Landscape Artist of the Year (2018) and Portrait Artist of the Year (2020).

Gil Dekel is a doctor in Art, Design and Media, specializing in processes of creativity and inspiration. He is a lecturer, visionary artist, Reiki Master/Teacher, and co-author of the ‘Energy Book’. He was awarded the Queen Elizabeth II Platinum Jubilee Coin, in recognition of his dedication and commitment to pastoral work at Hampshire Constabulary.