ESSAYS

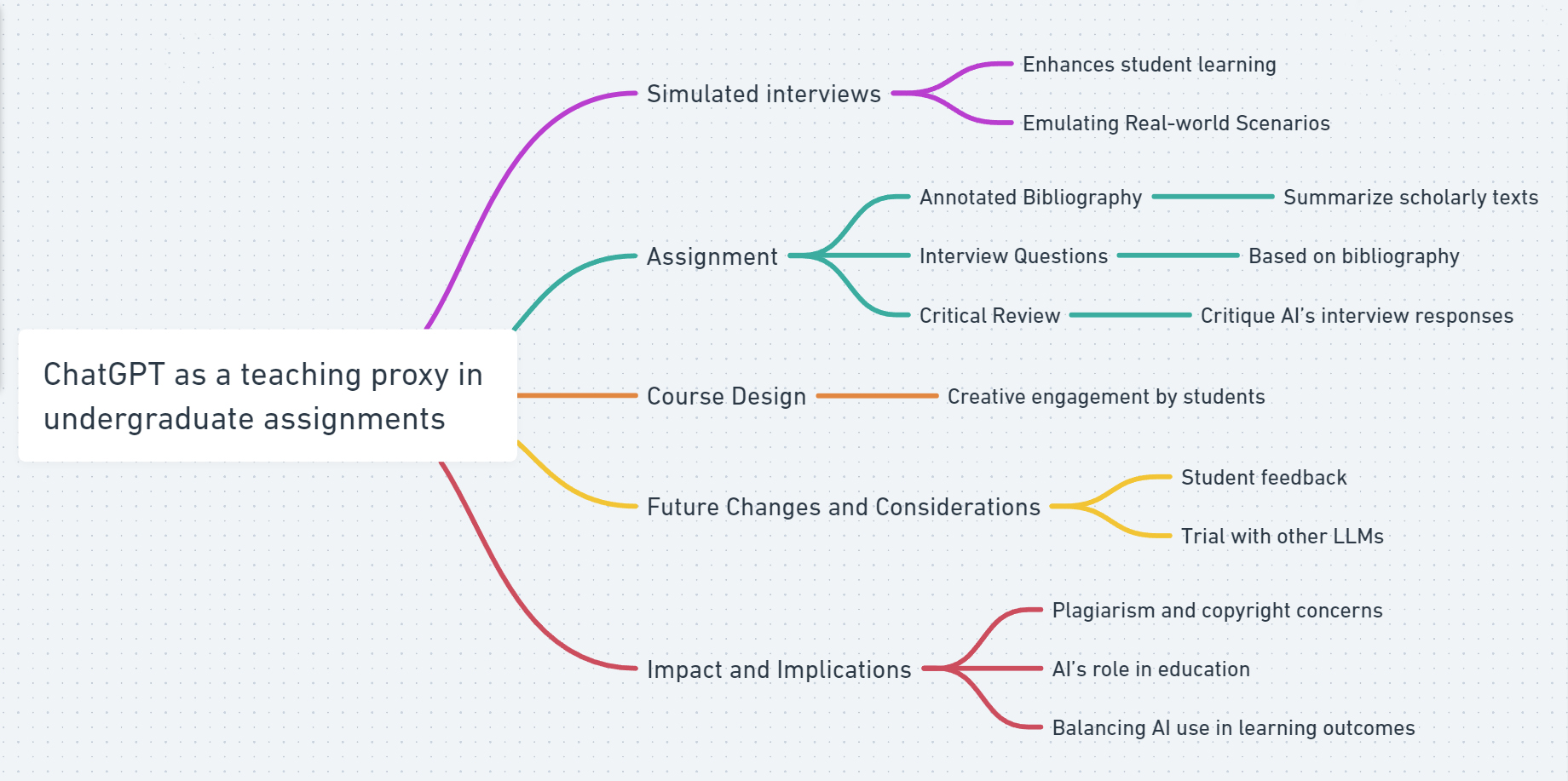

Who are you?: ChatGPT as teaching proxy in undergraduate assignments

5 July 2024 – Vol 2, Issue 3.

Abstract

Can ChatGPT be used to create challenging and creative assignments for undergraduate students? In this article, I discuss my use of ChatGPT as an interview proxy for students. Borrowing from the medical community’s concept of the Simulated Patient, I used ChatGPT to act as an imagined proxy (impersonate) for someone from the world of sports. Students from the undergraduate ‘politics of sport’ course subsequently interviewed the ChatGPT proxy using interview questions drawn from peer-reviewed academic research. The goal of this assignment was twofold:

- to challenge students to engage meaningfully with academic research and apply it to ‘real world’ situations (by emulating the ‘real world.’)

- to help students to consider the limits of ChatGPT when dealing with real world scenarios.

Fig. 1. ‘Working with AI in class.’ Generated through ChatGPT 4o, June 2024.

Although some issues did arise during the course, student feedback and coursework suggested that this is an engaging, fun and creative approach for students. This approach could, it is argued, be used fruitfully in a range of different academic subjects.

Introduction

Can ChatGPT and AI impersonate human beings and help students think more critically and creatively? Some, including myself, worry that Large Language Models (LLMs) such as ChatGPT would be used by students to complete assignments, avoid coursework and, ultimately, lose creative capacity and negate the point of a university education. These issues remain unresolved and have brought with them a mixed response from universities (Lin, 2023). Some universities have banned the use of LLMs entirely, while others have allowed students greater freedom in using them. The relative merits of each approach are for others to decide, and are unlikely to produce a definitive framework for the time being. When it became obvious that students had embraced LLMs and that my University allowed the use of LLMs, I returned to the question about AI and impersonating human beings but from a different approach. Could ChatGPT ‘pretend’ to be someone? And how would this enhance or improve my teaching practice?

Background and assignment structure

Prior to the emergence of LLMs undergraduate students (second year ‘Politics of Sport’ module) were given a ‘policy report’ for their end of year assignment. The premise was simple enough. Choose a problem with the world of sport – be it corruption, doping or gender pay disparities. Write a report summarising at least 10 pieces of scholarly work and provide recommendations to a government minister or sporting leader based on this problem. It was an effort to bridge the gap between theoretical and applied knowledge (Perkmann et. Al, 2021) in the hope of preparing them for their final year dissertation but also for any work post-University that they may do in sports. After three years of experimentation, and tweaking, it was clear that while students were searching for ‘real world’ problems, they struggled to apply research to these issues. As it became clear that I needed to revise the assignment, ChatGPT (and subsequently other) LLMs emerged. A new opportunity arose.

In medicine, a simulated patient (SP) is an actor hired to give medical students a chance to apply their knowledge in an interactive setting (Scherr et. al, 2023). The design is simple enough. SP enters the room, describes symptoms from a script to a trainee doctor who, through the course of an interview and examination, tries to determine the nature of SP’s illness. The value of this approach is that it is a low stake but highly specialised form of assessment (Scherr et. al, 2023). In the humanities, historians have re-enacted famous debates and court cases for teaching purposes while popular historians use war re-enactments to similar effect (Riddell, 2018). In effect, we want to emulate the real world through role playing and re-enactment. In the flurry of articles, studies and interviews concerning LLMs in University contexts, Scherr et. al’s (2023) article discussed ChatGPT as a simulated patient. Given their success, I began to experiment with ChatGPT as an SP within a sporting setting. The set up was simple enough. Tell ChatGPT to mimic a person from the world of sport be they the Head of the International Olympic Committee (IOC), an official within FIFA, a sporting journalist or a disgraced player. Once their alias assumed, the AI would then answer ten questions related to a topic of interest. The answers, while not stellar, did mimic the often anodyne and highly diplomatic responses which sporting officials and athletes have been trained to give in public (Smith and Watkins, 2018).

The assignments was this:

- A 500 Word Annotated Bibliography: Students were asked to choose a topic of interest in the world of sport. The only stipulation was that it was a ‘problem’ within sport. They were asked to write five summaries of one hundred words each outlining the main argument, methodology and findings of scholarly texts. This pushed students to specialize early in the assignment and prove their ability to engage with literature.

- 10 Interview Questions: Based upon the annotated bibliography students draft 10 interview questions for their AI Proxy.

- A 2,500 Word Critical Review: Students critique the AI’s interview transcript with reference to the accuracy of answers, the complexity of the responses and what was missed by the interviewee. This is done with reference to previous literature, and it is expected that students will have expanded on the references submitted in the annotated bibliography. Students were encouraged to include excerpts from their interviews and include the entire transcript in the appendix.

In practice, this meant two assignments (an annotated bibliography + interview questions and a critical review). This was the first time that my students were asked to formally incorporate AI into an assignment. Additional support was provided at several turns throughout the semester as were illustrative and tongue in cheek AI generated images to explain the assignment. The below image, inspired by the Scooby Doo television series of the 1960s and 1970s shows athletes ‘uncovering’ the AI pretending to be one of them.

Fig. 2. ‘So it was AI all along?’ Generated through ChatGPT 4, February 2024.

The second, slightly more dystopian, image, shows a robot operating as a puppet master with a sporting administrator marionette. These images were used as discussion points in class about how accurate and successful ChatGPT was in ‘passing’ for a sporting administrator. In one class example, we compared the AI’s answers to that of a well-known sporting administrator and found both to be similarly vague and anodyne.

Fig. 3. ‘AI as Sporting Proxy.’ Generated from ChatGPT 4, March 2024.

Fig. 4. ‘The ChatGPT Athlete?’ Generated from ChatGPT 4, May 2024.

The final image was used at the end of the semester to discuss how successful, or unsuccessful, students felt the proxy AI figure was.

Course design

From a teaching perspective, students engaged with this assignment in creative ways. Some decided to interview disgraced players about doping, others sporting officials about concussion and head trauma or gender disparities. These ideas were not prompted by my own suggestions but rather by the students’ consideration of a pressing issue within sport (say doping) and the best person to interview about that topic (a player who failed a drug test). Free to choose their own topic, students engaged with sporting issues and literature in ways I had not considered. In short, it challenged student’s creativity and critical thinking, and they responded well to it.

Future changes and considerations

From the sixty-two student questions in mid and end-of-semester surveys, the majority (fifty-eight) were satisfied or very satisfied with the assignment. Illustrative responses were that the assignment ‘was different and interesting’; that it ‘linked nicely from the first to second assignment’ and that it was ‘engaging and fun’. Others enjoyed the ability to ‘choose what to write about’. Whereas the previously used policy report assignment failed to adequately challenge students to think critically, the interactive nature of the assignment (through the proxy interview) pushed them to think about the questions they wanted to ask about critical issues in sports. A common theme from students was that they revised their interview questions when it became clear that the responses did not address the key issues raised in the research.

When this assignment was initially created many people saw LLMs and ChatGPT as interchangeable terms. The reality is far more complex given the multitude of rival AIs students can utilise from Google Gemini to Microsoft Copilot. My decision to use ChatGPT (at the time version 3.5 was freely available) was driven by two considerations: what were students already familiar with? What was free to use? Students were told to use version 3.5 which was the free service and had to provide evidence in the forms of screenshots and integrity statements that they did not use a paid subscription for a higher rated version. On using this assignment again, I will trial several more freely available LLMs to determine which responses prove best for this assignment.

The most difficult element of this assignment was undoubtedly the assessment areas. I did not want this assignment to be a simple case of showing that ‘AI is bad’ but rather I wanted students to engage with the interview responses and contextualise them with reference to research (Lopatto, 2003). The three headings chosen here (accuracy, complexity and what was missed) were illustrative of that goal. Students struggled to initially understand what ‘complexity’ meant as a point of critique within their assignments. Somewhat colloquially the phrase ‘what would this mean in real life?’ or ‘would this work in real life?’ or ‘have they simplified what is already happening?’ helped to clarify this point. Those students who previously struggled to understand what complexity meant reported no confusion at the time of submission. Several alternative words and phrasings could be: ‘real world application’, ‘applicability’, ‘effectiveness’.

At the time of writing, it is unclear just what impact AI will have on teaching. Issues of plagiarism, copyright and ‘old fashioned’ critical engagement are real and very concerning (Onal and Kulavuz-Onal, 2024). What is perhaps clearer is that AI’s involvement in education is unlikely to be rolled back or eliminated. Conscious that AI should not be uncritically incorporated into university education, nor should it be eliminated altogether, it is time to consider a middle way which uses AI to support existing learning outcomes. The ‘proxy method’ here, is one I believe has great benefit for those in the humanities and healthcare. It can act as an SP, an eleventh-century monarch, a disgraced athlete, an accused defendant, an Athenian philosopher and much more. Interaction and engagement are keys to learning. The trick for educators is to figure out the best way of using AI to achieve these aims. The proxy interview provides one potential pathway.

At a glance

Appendix

Sample prompt and interview questions for ChatGPT proxy

You are a senior FIFA official who specializes in diversity and inclusion initiatives. You are deeply involved in developing and implementing strategies to combat racism in football. Provide answers to the below ten questions and be as detailed as possible with your response. Make sure each response refers to initiatives, and provide examples.

- Q: How would you describe the current state of racism in football, and what are the most prevalent forms you are addressing?

- Q: Can you outline the key strategies FIFA is currently implementing to combat racism in the sport?

- Q: What emphasis is FIFA placing on educational initiatives to combat racism, both within teams and among fans?

- Q: Why do you believe racism remains an ongoing issue within sport?

- Q: Which football cultures seem to be the most prone to racism across Europe? Why is this the case?

© Journal of Creativity and Inspiration.

Images: Figure 1: AI and Gil Dekel. Figures 2-4: AI and Conor Heffernan’s students.

Dr. Conor Heffernan is a Lecturer in the Sociology of Sport at Ulster University where he teaches on the undergraduate program. At Ulster University Conor is part of the Student Wellbeing and AI working group teams. Additionally, Conor holds a Fellowship from the Higher Education Academy.

References

Bovill, C. (2019) A co-creation of learning and teaching typology: What kind of co-creation are you planning or doing?. International Journal for Students as Partners, 3(2), pp.91-98.

Clemitshaw, G. (2013) Critical Pedagogy as Educational Resistance: a post-structuralist reflection. Power and Education, 5(3), pp.268-279.

Lin, Z. (2023) Why and how to embrace AI such as ChatGPT in your academic life. Royal Society Open Science, 10(8), p.230658.

Lopatto, D. (2003) The essential features of undergraduate research. Council on Undergraduate Research Quarterly, 24(139-142).

Onal, S. and Kulavuz-Onal, D. (2024) A cross-disciplinary examination of the instructional uses of ChatGPT in higher education. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 52(3), pp.301-324.

Perkmann, M., Salandra, R., Tartari, V., McKelvey, M. and Hughes, A. (2021) Academic engagement: A review of the literature 2011-2019. Research policy, 50(1), p.104114.

Rahman, M., Terano, HJR, Rahman, N., Salamzadeh, A., Rahaman, S. (2023) ChatGPT and Academic Research: A Review and Recommendations Based on Practical Examples. Journal of Education, Management and Development Studies, 3(1), pp.1-12.

Riddell, J. (2018) Putting authentic learning on trial: Using trials as a pedagogical model for teaching in the humanities. Arts and Humanities in Higher Education, 17(4), pp.410-432.

Scherr, R., Halaseh, F.F., Spina, A., Andalib, S. and Rivera, R. (2023) ChatGPT interactive medical simulations for early clinical education: case study. JMIR Medical Education, 9, p.e49877.

Smith, S.A. and Watkins, B.A. (2018) Score! How collegiate athletic departments are training student-athletes about effective social media use. Journal of Public Relations Education, 4(1), pp.49-79.