Prof. Anita Shapira and Dr. Gil Dekel in a conversation.

Prof. Anita Shapira and Dr. Gil Dekel in a conversation.

Gil Dekel: How did you come across Natan Hofshi?

Prof. Anita Shapira: I came across Natan Hofshi’s name when I worked on the biography of Berl Katznelson. I did not do a research specifically on Natan.

The fascinating thing I found about Natan was his consistency as a pacifist. This was something unique to Natan. He was an unabashed pacifist all the way, including the times of the Second World War, and after, in relation to the world and to the Jewish community in Palestine and the state of Israel. And he never changed his views.

However, we must say that at the beginning of his life in Palestine (Israel) he went on guard duty, and he did hold arms during the duty. This was the only instance in his life where it seems that he did not follow the creed of pacifism.

Gil: This case was around 1912. Natan worked as a guard in the village of Gan-Shmuel. In that duty (or maybe there were a few?) he felt “as if I made a bond with the ‘Nagant’ [Russian rifle] which was always set ready to fire.” What he writes next is interesting: “But deep inside the thoughts never stopped! Is it not possible to go about it differently! Will the sword forever blaze a trail!” So, even then, he held a pacifist view.

Anita: Yes, however, if you hold a gun you can find yourself using it, if you need to… Maybe there was no need to use it. The interesting thing is this question: what made Natan such a strong pacifist, as indeed he was, all throughout his life?

But, how is that unique to Natan? Were there no others like him? Other pacifists and non-militarists who came from Russia, like him?

I don’t know. I did not find in Russia this trend among Jews or among non-Jews, after the revolutionary movement. On the contrary, they used arms. They fought the Tsar; they fought each other. Pacifism was not a part of the ethics at that time. It was something associated usually with European cultures – German cultures – and less so with East European cultures.

The German culture during those years (about 1901 – 1905) advocated pacifism?

No, I would not say that. But I would say that those Jews who came to Palestine and who were pacifists – those who followed the ‘Brit Shalom’ association – were mostly of German origin or at least associated with the German culture – the liberal culture.

Natan did not emigrate from Germany, but from the Russian Empire. And apart of him, I cannot remember another immigrant from East Europe that was so strong in his conviction of pacifism.

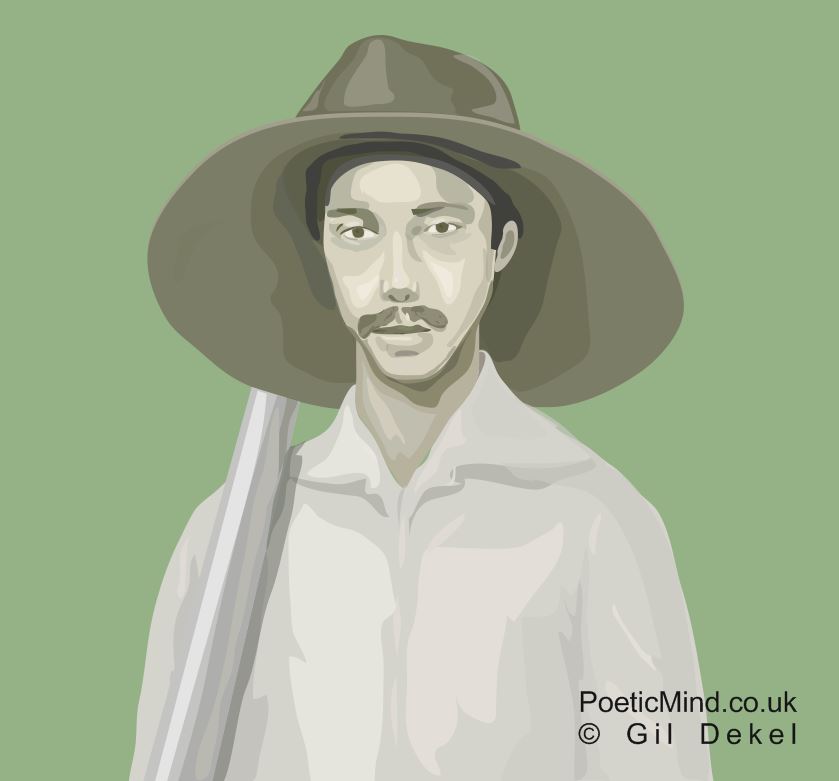

Natan Hofshi, drawn from a photo taken probably in Hadera, 1912. © Gil Dekel.

This is very interesting because I don’t know where he ‘took’ this opinion. There were many who were humanists, for example, the controversial figure of Manya Shochat. She was definitely a humanist and in her later years she was a partisan of the rights of the Arab minority in Israel. But she never gave it a thought whether to use arms or not. She took it for granted that she could use arms if she needed to. Indeed, she fought the Tsarist regime in Russia, and later fought in Israel – still, fighting did not change her basic humanist approach. She was a humanist. After the establishment of the state of Israel, she was very much on the left side of the political spectrum. This part-time militancy in defense of matters, so to speak, is a contradiction that we see in the liberal movement. Natan Hofshi, on the other hand, was pacifist and anti-militarist all throughout his life.

One of the teachers of Natan Hofshi was A.D. Gordon. Was he not pacifist?

No, he was not a pacifist. He was a humanist, but not a pacifist.

Natan quoted A.D. Gordon many times. They also knew each other very well. I thought Natan absorbed pacifism from A.D. Gordon, and of course, from Gandhi and Tolstoy?

I did not find any expression of pacifist principles in A.D. Gordon’s writings. Humanist, he was; yes. He advocated for the communion of the person with the land. Man and nature, yes. But not pacifism.

Tolstoy, as a young man, fought in the Russian army and became pacifist and a socialist later in his life. Gandhi, of course, is good example, but not the other two.

Are there any writings by A.D. Gordon advocating war?

No, no. But also nothing against armed self-defense.

Did he actively write in favour of self-defense or did he not touch on these issues at all?

I think he did not write at all about these issues.

It seems to me that Natan Hofshi created something new: a combination of ideals drawn from A.D. Gordon, Tolstoy and Gandhi.

Maybe… maybe he took from A.D. Gordon the ideal of communion with nature; from Tolstoy the life of simplicity and justice, and from Gandhi the pacifism.

I have scans of Natan’s personal journal, which I got from his daughter. You know, his handwriting was very beautiful. Do you think this has something to do with Zionism, and the love of the Hebrew Language?

Well, many of the people of his generation wrote beautifully. Their handwriting was very clear because they were taught how to write and how to hold the pen properly – they learned calligraphy. Not only in Hebrew, but in other languages, too. It was part of their education at that time, something that has vanished when we decided that children should have the freedom to write as they wish; so today we cannot understand their handwriting…

Natan Hofshi worked very hard when he came to Palestine. As a young man he was a work-man (Poel), a man who works the land. But one could ask: was this because he had no other job, maybe?…

This is something that was true to many workers at that time. They turned necessity into ideology, and this was beautiful. It was for them a way to build a country. Yet, most of them, when they could, preferred to do other jobs, like being editors, writers or teachers. Unfortunately, there were not many jobs in these areas.

So they took whatever they could.

Yes, yet, they made it into an ideology and this gave a halo of importance to the hard work. It made the work that was difficult, badly paid, exhausting, unclean and boring – it made that work into something of importance, of holiness. This is how people make their lives meaningful, even today.

If you give meanings to what you do then it’s easier. If it doesn’t have meanings, it’s just terrible work.

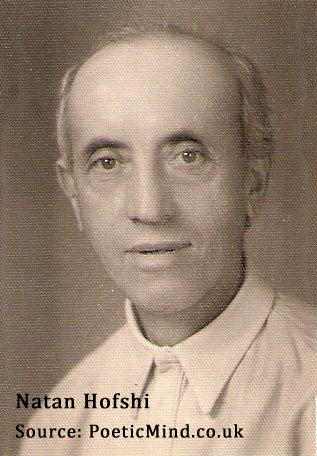

Photo of Natan Hofshi (nathan chofshi). Date unknown (probably before 1967). I inherited this photo from Lea Ben-Dror (daughter of Natan Hofshi). I hereby release the photo under license: Creative Common Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International.

There were some troubles between the local Arabs and the French?

Yes, this happened between 1918 and 1920. At that time the French ousted King Faisal from Damascus, and the Arabs saw the French as occupiers, which they were in a way. They occupied Syria. There was a no-man’s area which was still to be decided whether it would belong to Syria or Palestine. In the early ‘20s, it was agreed that it will become part of Palestine, under the British mandate. This area is near the source of the Jordan River and was part of the water resources for Palestine. Palestine needed it more than Syria, as Syria got abundance of water.

So France and The UK came to an agreement?

Yes. The demarcation was agreed by both sides, as they were allies. The British had the upper hand militarily in the area, so in a way there was an agreement. The British agreed that the French control Lebanon and Syria, and the French agreed to the border in the north and part of it becoming Palestine.

By the way, many historians agree today that the British mandate was crucial to the establishment of the state of Israel.

There is always the big question about land acquisition in Israel, before Israel was established in 1948.

Until Israel was established in 1948, the Jewish people did not take any land, and likewise the British government did not allocate them any government land. They paid for everything with good money. And the Arab leaders that were preaching against Jewish settlement in the country, were selling lands to the Jews at the same time.

The owners of the lands were living in Syria and Lebanon?

Not necessarily. Some of them lived in Palestine.

Was the situation different under the Ottoman Turks rule in Palestine?

The Turks would not allow to sell land but to Turkish citizens alone. So, if you were not a Turk citizen, the land had to be bought in a roundabout way through the intercession of a Jew that was a Turkish citizen. With the British mandate, the Jews were allowed to buy land until the 1940s when buying land was restricted.

I also hear that local people did suffer, so although the Jews did buy land legally and they paid for it good prices, those who sold them the lands did not care much about the Arabs that were living on the lands.

That’s true, but you know, there were more than one commission of enquiry into this matter during mandatory times, and they came up with a very low number of tenants being actually evicted, something like 600 people, which is bad and should not happen, but is not that terrible, I would say.

A colleague of mine said this: ‘When the state of Israel was established, Arabs who had sold lands were seen as sort of traitors as they had played a role in this establishment. That is why many or their descendants will now claim that they had no part in selling, and were forced out of their lands.’

But I guess that the important thing now is how to promote peace, so that people can live peacefully together.

30 Sep 2013. Photograph of Natan upload 7 Oct 2013.

Exclusive publishing rights © Gil Dekel.

The conversation took place on 8 Sep 2013 over the phone, and via email correspondence 27 Sep 2013. Prof. Anita Shapira lives in Israel. She is Head of The Nation State Project in the Israeli Democracy Institute, and professor emerita at the Tel-Aviv University. Anita’s webpage, click here. Dr. Gil Dekel lives in The UK. He is Associate Lecturer for the Open University’s design courses.

- Reading with Natalie, book here...

- Reading with Natalie, book here...