By Dr. Gil Dekel

How can colours support you in organising and designing information in your print or online projects? Here is a summary of the chapter ‘Colour’ from Tufte’s book ‘Envisioning Information’[1], with further suggestions I came across during my work as a design researcher[2]:

Colours are a powerful visual tool to represent information. Many people can identify as much as 20,000 colours – and the limit of 20,000 colours is reached not because of the capacity to discriminate between two adjacent colours, but simply because of the limits of the human vision and memory.

Colours can be compared to music. You need to have accent in music to create coherency. Yet if every note/word/movement is accented, then the result is that we have no meanings. Likewise, you do not need accents of too many colours everywhere on your page. You do not need too many dominant colours. Rather, you need colours that support each other on the page, with only a few colours that are accented (dominant) to create structure and hierarchy.

Red, green and blue (the primary colours) and black provide the maximum differentiation between them. No other four colours deliver such differentiation.

Colour is described in three categories: hue, saturation and value. Read more here.

Computer screens use red, green and blue – this is known as the additive method. The print industry uses cyan, magenta and yellow – this is the subtractive method. Read more here.

A good strategy to coming up with colours and their combination is to look at nature. Nature’s colours are ‘familiar’ to the human eye. The colours are also coherent and harmonious.

Grey colour is regarded one of the prettiest in art. It is seen as the most important and versatile colour. Muted colours (colours mixed with grey) provide the best backgrounds. Backgrounds need to be ‘quiet’, so to allow for even the smallest brighter area to stand out. Backgrounds need to support and ‘hold’ the important information on the page.

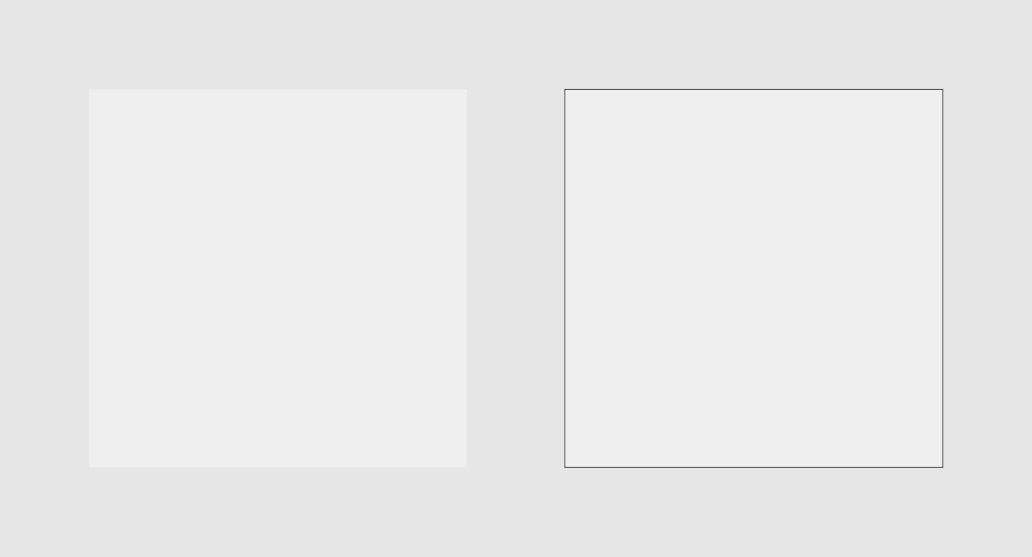

Colours depend on each other, and affect each other. When looking at colours they can ‘shift’, i.e. they look differently. This depends on adjacent colours and shapes. For example, the same colour will look different when placed on different background colours, as seen in figure 1. The colour of the small two squares is exactly the same, yet it shift slightly in our eyes because of the surrounding backgrounds. On the right the small square colour looks darker compared with the small square on the left…

Figure 1: the two small squares have the same tint, but look different as they ‘shift’ depending on their background colours. The small square on the right looks darker. (Image created by Gil Dekel. Image file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.)

In figure 2 are the two small squares, where you can see that they have the same colour:

Figure 2: The two small squares from illustration 1, juxtaposed here to show that they are the same tint. (Image © Gil Dekel).

Colour blind people cannot distinguish between red and green. If you differentiate information solely on the colours red and green, then they will not see it. For example, if you place a green circle next to red circle, then colour blind people will see both circles the same.

Human cognitive processing tends to emphasise the weight of a contour lines (the line around shapes or text), sometimes giving it more weight than it usually has.

The tint of a colour can look different when there is a contour line around the colour (shape), as seen in figure 3.

Figure 3: A contour dramatically changes the perceived tint, and also differentiate a colour (shape) from its background. The tint in the two squares is exactly the same.

Strong colours produce focus. If you add strong colours in areas which are not important on the page, then the focus will go there. The eye will be distracted to go there, and will not focus on the important details. Such visual ‘excitement’ produces little visual information.

In maps you do not need strong colours to delineate what is obvious, such as a sea area. You can simply outline the shape of the sea without added colour. A sea shape is already familiar to most viewers of maps, and if the important information is the land (inside area) then the sea (outer areas) should be given less emphasis.

© Gil Dekel. 21 July 2016.

Organising information through colours: design tips by Dr. Gil Dekel is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Footnotes:

[1] Edward R. Tufte. (1990) Envisioning Information. Cheshire, Connecticut, USA: Graphic Press. 3rd printing 1992.