Inspiration: a functional approach to creative practice.

PhD thesis in Art, Design & Media, by Gil Dekel.

10.1 Sensing

Noticing that something exists, or sensing it, is an initial experience in the artistic process.

Inner voice / listening / collective unconscious

Piirto (2005: 9) discusses the cravings for silence that artists report, asserting that artists are seeking isolation in quiet places in order to hear an ‘inner voice’ that would inspire them to create.

The English Romantic William Blake was open in discussing his experiences of an inner voice, and took it as a matter of fact. Beer (2003: 12) quotes from a letter Blake wrote to John Flaxman in 1800 where Blake refers to the daily events of his time, adding that ‘My Angels have told me that…’ Blake (Halpern, 1994: xv) declared that he is under the guidance of angels day and night. Charles Taylor, in his study of the Sources of The Self, asserts (1989: 368-369) that the inner voice is a crucial concept in the work of the English Romantics, to the extent that fulfilling the inner voice makes the act of artistic creation possible (p. 374). According to Taylor, the hearing of an inner voice is at the same time the act in which the artist defines and formulates the inner voice, and thus realises it. In that way, Taylor (p. 375) wishes to emphasise that it is not a matter of copying a model or carrying out an already determined form, but rather one of actively crafting it, of giving a shape to the inner voice. The inner voice cannot be fully known outside or prior to the articulation and definition of it. Artists know it only once they do it, according to Taylor.

However, Kandinsky, in his work Concerning the Spiritual in Art (1972), saw the inner call from a different perspective. Kandinsky asserts that the inner voice is a source that calls upon artists to create. Kandinsky sees the function of the inner voice as an active source in itself that inspires or motivates artists into action. In that respect the inner voice should not be confused with thoughts that run in one’s mind and which one hears in one’s own voice. According to Jung (1990: 82), the inner voice is stronger than the individual to the effect that it is ‘The voice of all mankind resounds in us’.

If an inner voice comes from beyond the psyche of the artist, and actively calls upon the artist, then one should wonder how artists come to hear this inner voice. The act of listening is a challenging one, as author Deepak Chopra asserts. Chopra (1995) argues that often people do not listen but rather tend to prepare answers even before the other has finished talking. If ‘normal’ listening may prove so challenging, how then do artists seem to accomplish an inner listening?

Wordsworth’s work The Prelude II, from 1805 (1971: 326–330) gives some clues to the way in which the artist listens. Wordsworth says:

‘I would stand,

beneath some rock, listening to sounds that are

the ghostly language of the ancient earth,

or make their dim abode in distant winds.

Thence did I drink the visionary power.’

Wordsworth opens the description of this scene by saying, ‘I would stand’. That act of standing is not carried out for the purpose of resting after a long walk, but rather for the purpose of ‘listening to sounds’, as the following line in the poem says. Wordsworth reveals that he simply stops, standing still, in order to enable the faculty of listening to take place. While Wordsworth stands ‘beneath some rock’ in a natural landscape scene, what he hears is not the sound of the moment but rather the ‘language of the ancient earth’, asserting that even if looking at nature, it is a contemplative moment where one listens to an inner voice. Listening to the inner voice was an important issue in the times of Wordsworth, where there was a growing awareness that identity is created out of a human’s own mentality, and not out of a theological deity (Jay, 1984: 33). As the Romantic period freed itself from religious myths, Wordsworth, according to Jay (1984: 39–40), asserted that one should work from within oneself, not from external influences.

Blake’s work Sconfitta (fig. 11) illustrates this idea. In this work the figure Urizen is depicted in a deep contemplative scene in front of the new world that he has created. Urizen, although the creator of that world, does not look at his creation, but rather stops and reflects by drawing inwardly. The mental act of stopping allows artists to draw inwards. With attention drawn inwards, the artist gains access to the voice that dwells within.

Figure 11: William Blake, Sconfitta (1795, frontpiece illustration for Song of Los.) Image in public domain.

The first part of Yeats’s book A Vision (1974; first published in 1925), written together with his wife, explains their method of automatic-speech of drawing inward where they would gain access to an inner voice, or what they called the ‘communicators’.

I have been following Yeats’s method, experimenting with automatic-speech with my wife. I decided to approach one automatic-speech experiment as if it is an art interview, where I would ask the ‘communicator’ questions. The questions and answers were made into the film Interview with authorial-Self (2007; ![]()

![]() see also revised transcript ). Yet, I noted one difference from Yeats’s description. Yeats (1974: 8) quotes his ‘communicators’ as saying, ‘We have come to give you metaphors for poetry’ whereas my experience with my ‘communicator’ revealed that he is a part of my own self, my own creative self, hence he defined himself not as a ‘communicator’ but as my ‘authorial-Self’. For this reason I have re-enacted the answers that were given to me by authorial-Self through my wife’s channelling, and using the computer I split the screen to include both ‘Gils’ – Gil who asks the questions on the left, and Gil the authorial-Self on the right (fig. 12).

see also revised transcript ). Yet, I noted one difference from Yeats’s description. Yeats (1974: 8) quotes his ‘communicators’ as saying, ‘We have come to give you metaphors for poetry’ whereas my experience with my ‘communicator’ revealed that he is a part of my own self, my own creative self, hence he defined himself not as a ‘communicator’ but as my ‘authorial-Self’. For this reason I have re-enacted the answers that were given to me by authorial-Self through my wife’s channelling, and using the computer I split the screen to include both ‘Gils’ – Gil who asks the questions on the left, and Gil the authorial-Self on the right (fig. 12).

Figure 12: Still image from the film Interview with authorial-Self (2007). Image © Gil Dekel.

In this way, I would suggest, drawing inwards can be said to allow the artist to open up to his or her own higher creative self. The idea of interacting with oneself is used widely in art, for example, in Gwen Stefani’s music video clip What You Waiting For? (2004), which deals with ways in which the artist becomes inspired to create art by acknowledging the inner self (fig. 13).

[Figure 13 – awaiting permission to include image here.]

Figure 13: Still image from Gwen Stefani’s video clip What You Waiting For? (2004). Image © Universal Music Publishing Ltd.

Artist Marcel Duchamp explains his invented alter-ego figure, Rrose Sélavy (1920s): ‘…not to change my identity, but to have two identities’ (From the display caption, Tate Modern, London, March 2008.) And the poet Shelley, according to Ackroyd (2006), described a vision in which he saw an image of himself walking towards him and asking, ‘how long do you mean to be content?’ In my case the opposite happened as I was the one to ask my ‘image’ questions.

The sense that the inner voice can exhibit itself as part of the artist can be illustrated with the creative process of painter Barry Stevens. Stevens (![]()

![]() para. 33) explains, ‘External and internal are for me like a spectrum or a continuum. The point at which one becomes the other is arbitrary’. Blake’s claim that ‘the human might… be linked to the divine’ (Beer, 2003: xii) is seen by Stevens not just as a link in which one point touches another, but rather as a continuum, a spectrum. This spectrum suggests that artists are connected to their inner voice, or source of creative energy, at all times, but at specific moments they acknowledge it, or open to it, and allow for the creative flow.

para. 33) explains, ‘External and internal are for me like a spectrum or a continuum. The point at which one becomes the other is arbitrary’. Blake’s claim that ‘the human might… be linked to the divine’ (Beer, 2003: xii) is seen by Stevens not just as a link in which one point touches another, but rather as a continuum, a spectrum. This spectrum suggests that artists are connected to their inner voice, or source of creative energy, at all times, but at specific moments they acknowledge it, or open to it, and allow for the creative flow.

If we agree that the artist is connected at all times to the creative source, we might ask whether each artist is connected to a so-called individual source, or whether they are connected to a collective or shared source, from which all draw. Poet Anne Stevenson (![]()

![]() para. 27) asserts that ‘…poetry is literally untranslatable. However… you can transfer the spirit of it from one language to another’. Stevenson reveals that there is a core essence, which she defines as spirit, which can be exhibited within all cultures, even when the language is non-transferable. Poet Maggie Sawkins suggests that this core essence can reveal itself not by being translated or transferred, but rather by splitting itself, as it seems, and presenting itself to people from different places. She (

para. 27) asserts that ‘…poetry is literally untranslatable. However… you can transfer the spirit of it from one language to another’. Stevenson reveals that there is a core essence, which she defines as spirit, which can be exhibited within all cultures, even when the language is non-transferable. Poet Maggie Sawkins suggests that this core essence can reveal itself not by being translated or transferred, but rather by splitting itself, as it seems, and presenting itself to people from different places. She (![]()

![]() para. 15) says: ‘You could dream similar dreams to someone who lives in Africa, even if you are from a completely different culture’.

para. 15) says: ‘You could dream similar dreams to someone who lives in Africa, even if you are from a completely different culture’.

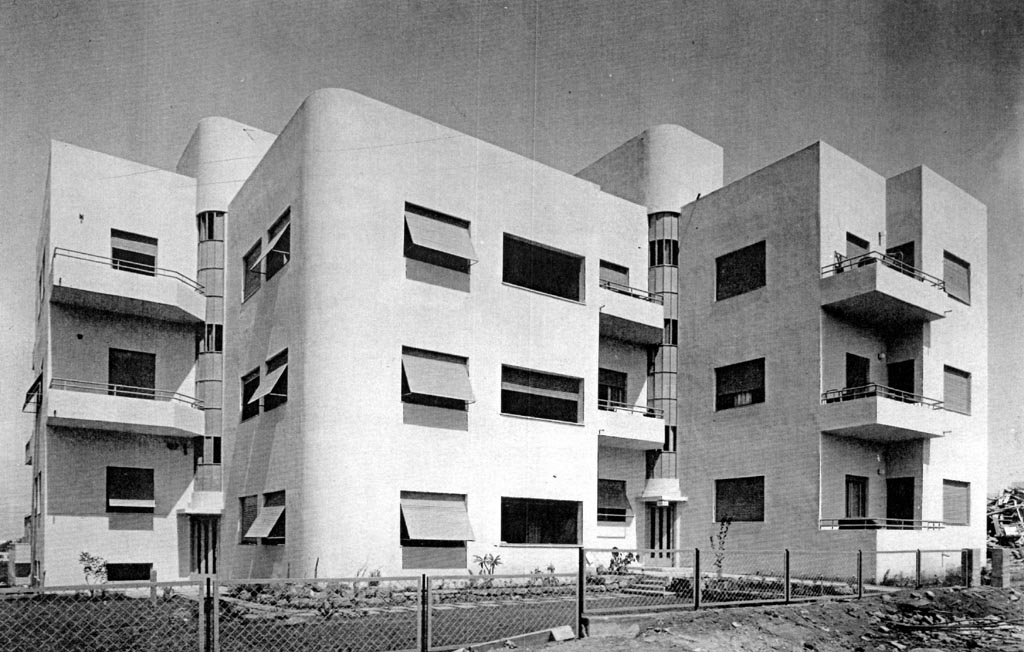

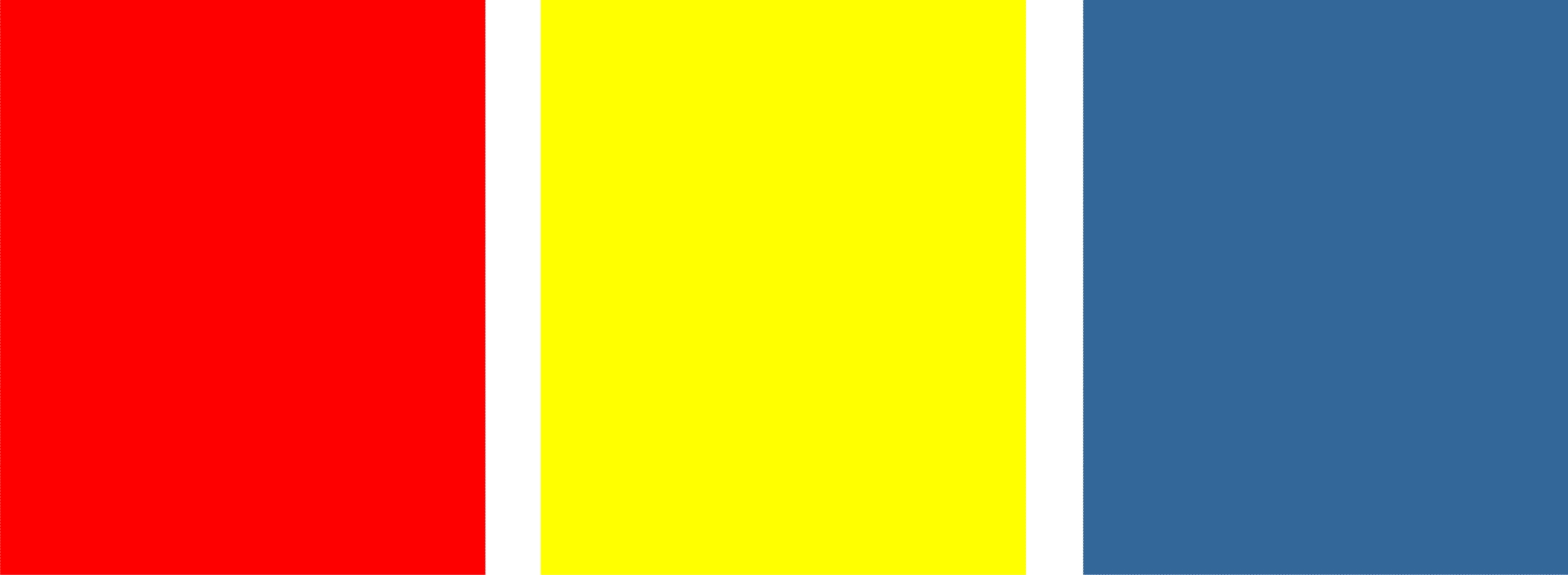

Shared ideologies that inspire simultaneously different art movements can be seen through art works. For example, the German Bauhaus and the Russian Constructivism movement, were operating in the early 20th century at a great distance from each other, yet they shared similar ideologies. The Bauhaus’s social ideology of using functional and simple shapes covered with a single colour (Aynsley, 2001: 61) (fig. 14) were also inspiring the Russian Alexander Rodchenko’s social ideology of functionality and use of single colour and simple shapes (Dabrowski, 1998: 57) (fig. 15). The Bauhaus applied this ideology in architecture, and Rodchenko in painting.

Figure 14: A Bauhaus style building as part of ‘White Tel-Aviv’ (1933). Architect: Yitzhak Rapaport. Image in public domain.

Figure 15: Illustration (by Gil Dekel) of Rodchenko’s Pure Red Colour, Pure Yellow Colour, and Pure Blue Colour (1921, oil on canvas, each panel, 62.5 x 52.5 cm.) Original work in Moscow, A. Rodchenko and V. Stepanova Archive.

Carl Jung (1990: 80) argues that people draw from a central source, which he defines as a collective unconscious. The collective unconscious draws on all cultures that exist today as well as cultures of the past. More so, Jung (1990: 56) asserts that shared thoughts seem to turn into shared actions, in what he termed synchronicities (Jung, 1963: 356). These synchronicities hold meaningful coincidence or equivalence of psychic and physical states, which have no causal relationship to one another, as Jung explains, but which inspire artists into actions. The various poets, authors, painters, and installation artists that I have interviewed shared the feeling of an urge to create that comes from a ‘mysterious’ place. Painter, poet and philosopher Paul Hartal (![]()

![]() para. 8) explains:

para. 8) explains:

‘…intuitions, imagination, emotions, ideas, memories, thoughts and dreams are not independent events of an autonomous brain and nervous system. We are an integral part of nature and cognitive processes occur in an organism sustained by its environment. They take place in a body that interacts with the biosphere and the entire universe.’

In this way, the collective unconscious is not just a pool of shared creative energy, but rather the originating source to which all actions can refer. However, people seem to exhibit different ways or points of view through which they express the creative energy emerging from the collective unconscious.

To understand how people respond to the same ideas I carried out different forms of engaging audiences to receive varied feedback. The first film that I created for this research, Quantum Words (2006; ![]() ), was showcased in a few different forms: in conferences at universities as part of paper presentations, online (youtube.com/gldek), and sent by post as a DVD for people I knew or contacted, for them to watch at home. Although this film was viewed online more than 1200 times (prior to 2009), I received only a few responses through the online medium. Written feedback from eighty people was collected through conferences presentations, emails, and guest books placed at exhibitions where the film was screened (

), was showcased in a few different forms: in conferences at universities as part of paper presentations, online (youtube.com/gldek), and sent by post as a DVD for people I knew or contacted, for them to watch at home. Although this film was viewed online more than 1200 times (prior to 2009), I received only a few responses through the online medium. Written feedback from eighty people was collected through conferences presentations, emails, and guest books placed at exhibitions where the film was screened (![]() ). The feedback covered the following themes: personal points of view, associations, use of graphic style, images, words, sounds, narrative, and philosophical ideas that viewers noted.

). The feedback covered the following themes: personal points of view, associations, use of graphic style, images, words, sounds, narrative, and philosophical ideas that viewers noted.

Conflicting interpretations were also noted, such as ‘Idea of Now which you speak about links with quantum physics’ versus ‘… the ‘quantum’ analogy doesn’t work’. Or, ‘…word made visual’ versus ‘Image ≠ word’. And while some ‘…felt: quite a strong resistance’ to the film, others claimed it was ‘Original, beautiful, sublime. Better than anything I’ve seen in Documenta…’ or ‘Made me smile… Enlightenment is fun’.

More so, the production of the film itself enabled me to have two different points of view, as I noted down in my diary during the making of the film (17 February 2006). Before making the film its initial images had captivated my mind and I saw them as if I was the participant looking outside, and seeing light sources downing from above and bursting from within me. Yet, while preparing the story board for the film I saw the scene from ‘outside’, as a director looking through the camera and seeing the actor (which resulted in the final camera angle shot used in the film) (fig. 16). I became an observer of my own mind’s images, looking at them from outside and sketching them for the story board. While the initial theme of the film remained, my perspective on it changed, transforming my point of view from a participant within the scene to an observer from without the scene.

Figure 16: Still image from the film Quantum Words (2006). Image © Gil Dekel.

While the duration of Quantum Words is one minute and forty-two seconds only, still it managed to stir so many different responses from viewers as well as myself. Such diversity indicates that people do not interpret what they see based on external patterns of social dogmatic thought, but rather based on their personal associations and identity. However, identities may not seem separated faculties. To quote from one feedback received on this film: ‘Identity is not the property of any one individual. The creative process is the identification itself’ (![]() ). In that respect, variations symbolise a shared activity of presenting collective unconscious from different perspectives. While we discuss such terms as identity and ‘individuation’, as Jung (1963: 352) puts it, it seems that these terms contain both the private individual as well as the collective that belongs to the whole human race.

). In that respect, variations symbolise a shared activity of presenting collective unconscious from different perspectives. While we discuss such terms as identity and ‘individuation’, as Jung (1963: 352) puts it, it seems that these terms contain both the private individual as well as the collective that belongs to the whole human race.

The initial sense that triggers artists is enabled by drawing inwards, where artists connect to a collective unconscious which is not individual but rather shared by all people. Artists sense, or become aware, of the inner and outer environment. This experience is then followed by feelings, emotional intensities that well up in the artists.

Table of Content: