Inspiration: a functional approach to creative practice.

PhD thesis in Art, Design & Media, by Gil Dekel.

10.3 Acknowledging

With heightened emotions and an urge to create comes a process of acknowledgement, where the artist makes an intuitive response to the creative feelings, through producing inner words and images. I see this as a process which stands both as a creative form in itself, where emotions are transformed into words and images in the mind of the artist, and as a process in which the artist registers emotions that are later transformed into art works. This process is not an intellectual self-analysis, but a form of recognition and registration.

The process of acknowledging will be examined through the categories word and image.

Word / Image

Robin Skelton (1978: 19–20) describes the feelings of identification that children have with the environment around them. Skelton explains that as we grow up we then start to give names to objects, and in that way objects are then treated as if they are independent of ourselves, turning into what he calls an ‘outness’.

By using words to give names, people separate themselves from things and emotions, and then observe them. Observation allows people to examine the relations they have with things and emotions, hereby producing meanings. Abraham Maslow (1994: 89) argues that the use of words has the power of removing inhibition and blocks that prevent people from expressing peak-experiences. He (1994: 90) suggests a method by which people learn to observe their experiences and then to label them, giving them names. Myra Schneider (![]()

![]() para. 24) shares her experiences in which words help to ‘…sort out ideas… crystallising thoughts and emotions… outside you… you can understand it much better. You have partly separated yourself’.

para. 24) shares her experiences in which words help to ‘…sort out ideas… crystallising thoughts and emotions… outside you… you can understand it much better. You have partly separated yourself’.

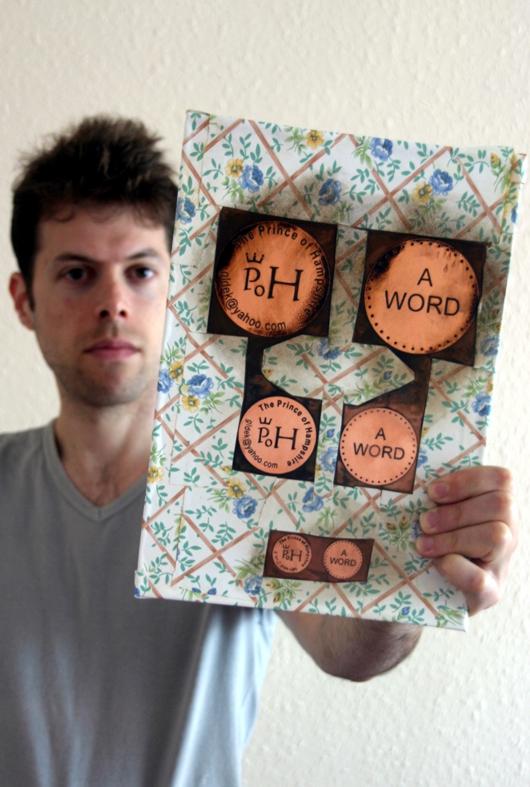

In a performance made into the film The Prince of Hampshire (2006; ![]() ) I have partly separated myself by inventing a personality, the Prince of Hampshire (figs. 29-30) who admits being both a prince as well as the PhD researcher, Gil Dekel, myself. The character prince reflects on this, as part of the film, explaining:

) I have partly separated myself by inventing a personality, the Prince of Hampshire (figs. 29-30) who admits being both a prince as well as the PhD researcher, Gil Dekel, myself. The character prince reflects on this, as part of the film, explaining:

‘Apart [from] my duties as the Prince of Hampshire, I am also a full-time International PhD student, at the University of Portsmouth… and I was wondering what is the connection between my duties as the Prince of Hampshire and my duties as a PhD student?’ (minute 1.30).

Figure 29: Still image from the film The Prince of Hampshire (2006). Image © Gil Dekel.

Figure 30: Production image from the film The Prince of Hampshire (2006). Image © Gil Dekel.

As an answer to that question, the character prince asserts in the film that words do not only help us to reflect and understand ourselves better, but rather help us to understand our position in the social and historical context. With the written documents that we have we can know what happened in the past, and we can assess where we are now. The character prince says:

‘It is thanks to the written words that commemorate past kingdoms that you can read about these kingdoms today, and know them… without the written words you will not remember the great achievements of [such as] Napoleon, no matter how much he was successful. It is not the ‘great conquests’; it’s the great writings…’ (minute 2.40).

In that respect words allow people to look at themselves, both by looking inside, making meanings of their feelings, as well as by looking outside at their historical and cultural position, observing the collective social development in which they take part.

I have attempted to give shape to this observation, turning words into an artefact that will serve as a reminder to audiences for the duality of looking inside and outside, and so I have attempted to create a coin that the character prince would give as a free gift together with the DVD of the film. For the observe side of the coin I designed the prince’s figure – representing the historical motif of the emperor’s face on a coin. For the reverse side of the coin I designed the text ‘A Word’ – representing the monetary value in the prince kingdom – words as a currency of exchange, instead of money (see test etching on cooper sheet, fig. 31).

Figure 31: Etching test for Prince Coin, for The Prince of Hampshire (2006). Image © Gil Dekel.

Words, in that imagined kingdom, symbolise the highest value that one can share – the authority of the speaker, his or her ‘own word’. As a token to this authority, I have decided to wear the prince’s costume while designing the coin on the computer (fig. 32).

Figure 32: Design of Prince Coin on the computer, for The Prince of Hampshire (2006). Image © Gil Dekel.

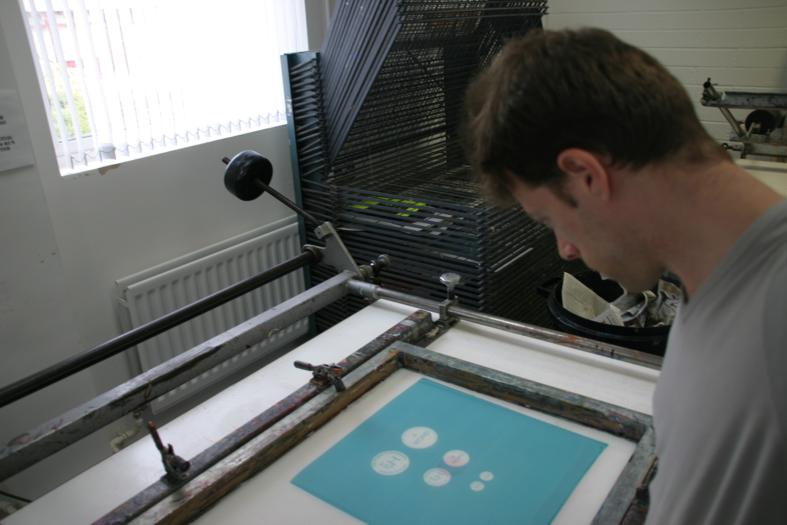

For the making of the coin I have experimented, with help from others, with a stamping process using a mint (figs. 33-34), wax engraving for pouring lead (fig. 35), clay (fig. 36), silk screen and acid etching (figs. 37-39), and embossing on metal sheets (fig. 40). I also considered the simpler way of designing the DVD as a coin, as well as commissioning commercial companies to take a 3D scan and produce a die-cast coin (however, the quotes I received for this task amounted to more than £800 for producing a quantity of 300 coins).

Figure 33: Mint for making Prince Coin, for The Prince of Hampshire (2006). Image © Gil Dekel.

Figure 34: Mint for making Prince Coin, for The Prince of Hampshire (2006) (image altered in Photoshop). Image © Gil Dekel.

Figure 35: Wax engraving for making Prince Coin, for The Prince of Hampshire (2006). Image © Gil Dekel.

Figure 36: Clay testing for making Prince Coin, for The Prince of Hampshire (2006). Image © Gil Dekel.

Figure 37: Acid etching for making Prince Coin, for The Prince of Hampshire (2006). Image © Gil Dekel.

Figure 38: Acid etching for making Prince Coin, for The Prince of Hampshire (2006). Image © Gil Dekel.

Figure 39: Acid etching on cooper for making Prince Coin, for The Prince of Hampshire (2006). Image © Gil Dekel.

Figure 40: Embossing on metal sheets for the making of the Prince Coin, for The Prince of Hampshire (2006). Image © Gil Dekel.

For cost reasons the final coin was not made, however I was left with a few attempts that culminated in artefacts that are works-in-progress. These ‘half-completed’ objects can be seen as ‘open artefacts’ indicating in a few ways that one can follow how to make the coin. In that way, the possibilities become the artefact.

Koestler (1964: 173) explains that words crystallise thoughts by making precise the vague images, and articulating intuition. Likewise, the painter Malevich (Drutt, 2003: 34) asserts that ‘the pen is sharper’ than the brush, and that by writing with the pen it can ‘…obtain the turns of the mind’. Since words are tools of expression I have tried to crystallise the act of words themselves, in the form of a coin, producing something ‘made’ of a word and that could be held and seen by audiences. My feelings, as Kapoor (Kapoor, Bhabha & Tazzi, 1998: 11) explained above, are that artists should make the tools of expression visible, not necessarily say something new.

For Rudolf Steiner, the attempt to visualise the act of a word may be seen as altogether unnecessary, since words are seen by him as an integral part of one’s own body. Steiner (1972: 10) argues that the use of words is so inherent that it operates with the orientation of the body in space. Speaking, Steiner says, is the outcome of walking, where forces of movement are carried to the head structure. As such, walking turns to speaking, and speech becomes one’s orientation in space. Steiner wishes to assert the importance of the inherent tools of speaking through words and thinking in words. Perhaps for that reason, Yeats (1966: 99) states that words spoken with intensity in public turn powerful, becoming more than the mere verses. It could be argued that Yeats acknowledged Steiner’s argument that an intensified and authentic speech produces an expression of the true self of the person, which Yeats calls ‘more than the mere verses’.

I have sensed Yeats’ ‘more than the mere verses’ throughout my performances, poetry readings, and paper presentations where a feeling of inner power was welling up within me while giving my talks or readings. This creative power helped me to speak in front of many varied audiences, in a clear strong voice. In times, my sentences may have been far from perfect, yet the voice was always strong, delivering the inner essence if not the ‘outer’ essence (the meanings of the words said.) This was evident in one conference presentation which was made into the video Trembling Words (2006). The content of my presentation was accepted by half the audience but rejected by the other half. Likewise was the feedback in regards the way in which I combined the ‘normal academic’ presentation format with some artistic presentation or performance. Yet, the intensity seemed to express itself and externalise the inner voice, which was credited by all the audience.

Following this I have noted that people do not listen only to the content of words but also to the energy behind it. Critic and artist Robert Morris (1989: 339) observes that a word in a text ‘…works by gaps and discontinuities,’ where one word means something else compared to the next word, and as such ‘language shows only differences’. Borrowing this idea for art I would suggest that if one looks at a painting one observes a complete picture with forms and shapes, but reading a text one observes the white gaps between the black words. Each word in that way can be seen as a separate island. The Dada art movement discussed at length its belief that each word contains a few meanings, not a single meaning.

However, Skelton does not focus on the discontinuity or the several meanings of each word. Instead, Skelton (1978: 13) focuses on the context, believing that the appearance of words on the page actually produces their meanings through the reference. A word appearing next to a word, Skelton explains, can determine the quality of the word. He summarises by saying that people do not accept a single meaning as a basis for words, but rather they allow meanings to be enriched by their context.

Artist Ken Devine (![]()

![]() paras. 13-15) discusses the multiple meanings of words, saying:

paras. 13-15) discusses the multiple meanings of words, saying:

‘…behind the ‘simple’ things that people say lie complex relations that they have with life, and they use language to convey that. Language is illogical… [it] is saying something which is partly true and partly false. Rarely can you say a complete truth…’

Devine (para. 24) refers to points of view, suggesting that we create meanings depending on context, ‘Whether something is true or false, that is a matter of position, a point from which we see it’. The complexity of words and the inherent energy which they contain is described by TS Eliot (1970: 30): ‘Words are best when they say things we no longer need to say’. Following Eliot’s assertion, and borrowing from Non-objective art, we may speak of ‘Non-objective language’. I see Non-objective language as an art form where words are stripped of representation. In one respect words already have a side to them where they are stripped of their representative meanings, and seem to have a visual shape: words that are printed on a page become ‘a shape on the page’, as Wilmer (![]()

![]() para. 38) notes. Likewise, concrete poetry tries to create a shape using the printed words on the page. The Italian Futurism art movement in the early 20th century is known for its use of layout of ‘bursting’ shapes of words across the page – words becoming an image.

para. 38) notes. Likewise, concrete poetry tries to create a shape using the printed words on the page. The Italian Futurism art movement in the early 20th century is known for its use of layout of ‘bursting’ shapes of words across the page – words becoming an image.

Like word, image is a representative tool used by people to understand reality. More so, it is natural for people to think that what they see represents things as they truly are, asserting the famous dogmatic view: ‘I will believe it when I see it’. Yet, Morris (1989: 339) reminds us that just like words, images are also representational signs, implying that images are indicating different things than the observed. Alan Corkish (![]()

![]() para. 23) reveals how this may happen, saying that ‘…photographs often capture unexpected pointers or markers to other things’. By capturing the ‘unexpected’ images come to serve as ‘…markers to other things’. Yet, the ‘unexpected’ does not suggest that a thing was not there to begin with, but rather that a person did not expect or did not pay attention to it. By not expecting, the observer may overlook it. The presence of visible things may only be noticed later, in the example of Corkish, by looking at it again in a photograph.

para. 23) reveals how this may happen, saying that ‘…photographs often capture unexpected pointers or markers to other things’. By capturing the ‘unexpected’ images come to serve as ‘…markers to other things’. Yet, the ‘unexpected’ does not suggest that a thing was not there to begin with, but rather that a person did not expect or did not pay attention to it. By not expecting, the observer may overlook it. The presence of visible things may only be noticed later, in the example of Corkish, by looking at it again in a photograph.

Installation artist David Johnson (![]()

![]() para. 40) asserts that while things might be ignored, still they are registered and remain, as he says, ‘…in the back of my mind…’ In that respect even when not consciously noticing things, still they are captured and registered. Jung is well known for his research on the images that are registered in one’s unconscious, ‘absorbed subliminally’ as he (1972: 23) puts it. Yet, Jung also has an important theory regarding the conscious mind and the way that it seemingly ignores things. He (1963: 184) argues that the act of ignoring happens after the conscious mind has allowed images to rise. As the images rise, we ‘…wonder about them a little,’ and we then neglect them, not trying to understand them. According to Jung, images are fully present in the thinking aware mind, and are not ignored but rather neglected.

para. 40) asserts that while things might be ignored, still they are registered and remain, as he says, ‘…in the back of my mind…’ In that respect even when not consciously noticing things, still they are captured and registered. Jung is well known for his research on the images that are registered in one’s unconscious, ‘absorbed subliminally’ as he (1972: 23) puts it. Yet, Jung also has an important theory regarding the conscious mind and the way that it seemingly ignores things. He (1963: 184) argues that the act of ignoring happens after the conscious mind has allowed images to rise. As the images rise, we ‘…wonder about them a little,’ and we then neglect them, not trying to understand them. According to Jung, images are fully present in the thinking aware mind, and are not ignored but rather neglected.

This suggests that the act of neglecting images is an act where the conscious mind represses images back to the unconscious. Paskin’s (![]()

![]() para. 6) argument that she feels as if working ‘…from a place that you might not have such an easy access to,’ can assert that images do rise up to the working consciousness but are later repressed, leaving the artist with a feeling that she is fully in the creative work and yet unaware to its rising content. In that way the conscious mind manages to capture images coming from the senses and then repress them, which I will term ‘repressivism’. Repressivism does not refer to those images repressed in the unconscious. Rather repressivism refers to the act of the conscious mind to contemplate images, to repress them, and to give us the illusion that images bypassed the conscious mind and were directly repressed in the unconscious.

para. 6) argument that she feels as if working ‘…from a place that you might not have such an easy access to,’ can assert that images do rise up to the working consciousness but are later repressed, leaving the artist with a feeling that she is fully in the creative work and yet unaware to its rising content. In that way the conscious mind manages to capture images coming from the senses and then repress them, which I will term ‘repressivism’. Repressivism does not refer to those images repressed in the unconscious. Rather repressivism refers to the act of the conscious mind to contemplate images, to repress them, and to give us the illusion that images bypassed the conscious mind and were directly repressed in the unconscious.

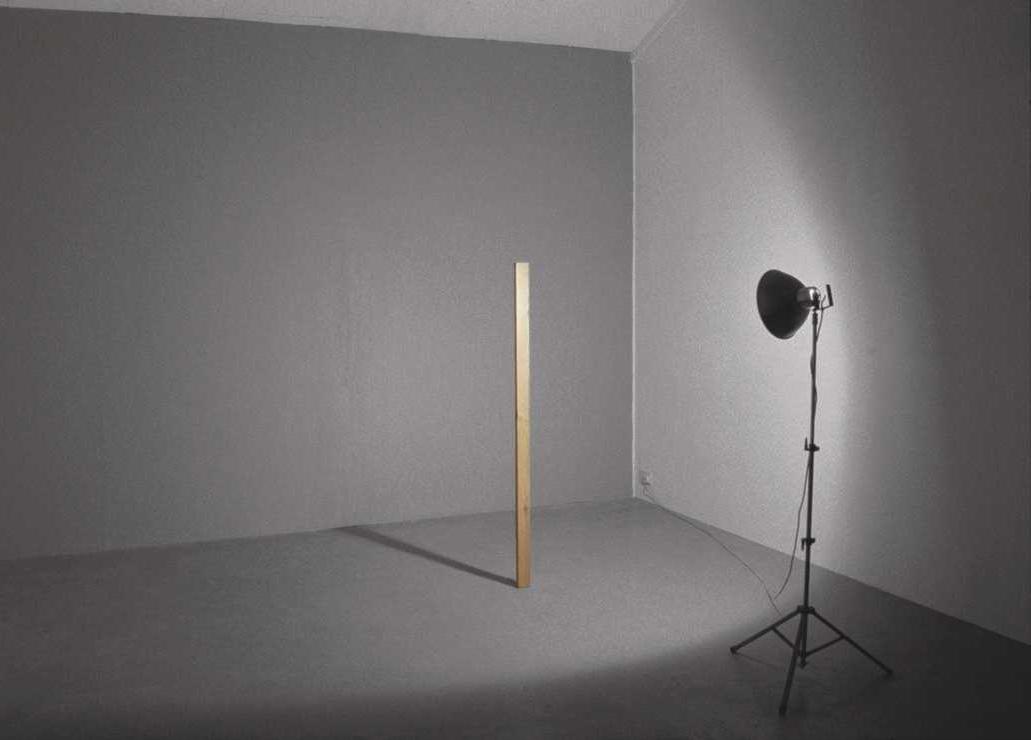

If we accept this assumption, we should then consider whether there is enough research that examines this process. Many authors, such as Alma, Wyllie & Ramer (2002: 65) in their important study on developing creativity, suggest forms of creativity, or intuition as they see it, as productive forms that bypass the conscious mind and that we should learn to connect to. While these studies are important for informing the creative powers that are not subjected to conscious or logic, it is also important to note the counter-creative power of the conscious mind to produce blocks. Such blocks seem to leave the artists with the feeling of knowing things and yet not being fully aware of them. David Johnson (![]()

![]() para. 18) deals with this duality, trying to illustrate it in his works, ‘…something that you could not see yet is the centre of the work… things you cannot see but know about, therefore affect the way you see: the non-visible’. In his work Trying to Imagine Not Being (2003) he painted out the shadow that a post casts on a wall. The shadow is noticeable on the floor, running to the wall – but does not exist on the wall where it should be (fig. 41).

para. 18) deals with this duality, trying to illustrate it in his works, ‘…something that you could not see yet is the centre of the work… things you cannot see but know about, therefore affect the way you see: the non-visible’. In his work Trying to Imagine Not Being (2003) he painted out the shadow that a post casts on a wall. The shadow is noticeable on the floor, running to the wall – but does not exist on the wall where it should be (fig. 41).

Figure 41: David Johnson, Trying to Imagine Not Being (2003, floodlight, post, emulsion paint, black wall painted so shadow disappeared, variable dimensions.) Image © the artist. Permission to use image obtained from the artist.

Casting one’s own shadow on the same part of the wall reveals what Johnson (para. 9) calls a ‘white ghost’ (fig. 42).

Figure 42: David Johnson, Trying to Imagine Not Being (2003, floodlight, post, emulsion paint, black wall painted so shadow disappeared, variable dimensions.) Image © the artist. Permission to use image obtained from the artist.

Image, I would say, is a symbol used by artists to denote something else, something which we cannot see. Even poetry, whose main tool is words, ‘…does use images to try to convey abstract thoughts and feelings…’ (Maggie Sawkins ![]()

![]() para. 17). The way in which artists approach the invisible and the abstract is explained by the Constructivist Naum Gabo (Annely Juda Fine Art, 2003: [4]). Gabo says, ‘Artists do not observe the world, but live the world’. Gabo asserts that artists do not look at reality in the common sense, but rather have a different mode of absorption of images – the ‘living’ in the world; the experiencing of it.

para. 17). The way in which artists approach the invisible and the abstract is explained by the Constructivist Naum Gabo (Annely Juda Fine Art, 2003: [4]). Gabo says, ‘Artists do not observe the world, but live the world’. Gabo asserts that artists do not look at reality in the common sense, but rather have a different mode of absorption of images – the ‘living’ in the world; the experiencing of it.

The artists that I researched tend to say that experiencing the world becomes a mode of seeing, which provides them with the perception of seeing beauty around them, or as Mondrian (Mondrian, Holtzman, & James, 1993: 15) defines it, ‘…a monument of Beauty…’ Hartal (![]()

![]() para. 37) goes even further, suggesting that ‘We have the historical evidence that humans even under the most dreadful conditions are capable of retaining their lofty spirit and inner dignity’. The ability to see the lofty and the beautiful in life can be argued as an ever present faculty within the artist. This ‘sense of beauty’, as I call it, suggests that the artist’s visual perception does not rely on what the artist sees from the outside but rather relies on his or her inner spirit. The artist looks at the world, but renders the images with the beauty that he sees inside. Emotion and visual perception are united, in what I would like to call the ‘emotiovisual’ faculty of artists.

para. 37) goes even further, suggesting that ‘We have the historical evidence that humans even under the most dreadful conditions are capable of retaining their lofty spirit and inner dignity’. The ability to see the lofty and the beautiful in life can be argued as an ever present faculty within the artist. This ‘sense of beauty’, as I call it, suggests that the artist’s visual perception does not rely on what the artist sees from the outside but rather relies on his or her inner spirit. The artist looks at the world, but renders the images with the beauty that he sees inside. Emotion and visual perception are united, in what I would like to call the ‘emotiovisual’ faculty of artists.

I have noticed the creative power of the emotiovisual faculty during the making of the short film Whispers in the Dark (2006; ![]() ). The film portrays the unfortunate event of a war which affected my family. Through the emotiovisual faculty I have edited images and wrote poetry that identified with both sides of the conflict, and helped to elevate pain through what I attempted to be a positive outlook through human disasters (fig. 43).

). The film portrays the unfortunate event of a war which affected my family. Through the emotiovisual faculty I have edited images and wrote poetry that identified with both sides of the conflict, and helped to elevate pain through what I attempted to be a positive outlook through human disasters (fig. 43).

[Figure 43: awaiting permission to upload image]

Figure 43: Still image from the film Whispers in the Dark (2006). Image © AP Photo/Ariel Schalit.

Through the emotiovisual faculty I could deal with observed pain not by debasing it (which brings more condemnation and thus more pain) but rather by an act of seeing and bringing out the beauty. As one feedback on the film asserts, ‘The film offers a… perspective on ways of living together in peace without denying the aggression and loss of life that has occurred’ (![]() ). To borrow from this description, I would say that one can condemn the fire for burning a forest, yet one may also observe the power of the trees to restore themselves and grow once again after the fire.

). To borrow from this description, I would say that one can condemn the fire for burning a forest, yet one may also observe the power of the trees to restore themselves and grow once again after the fire.

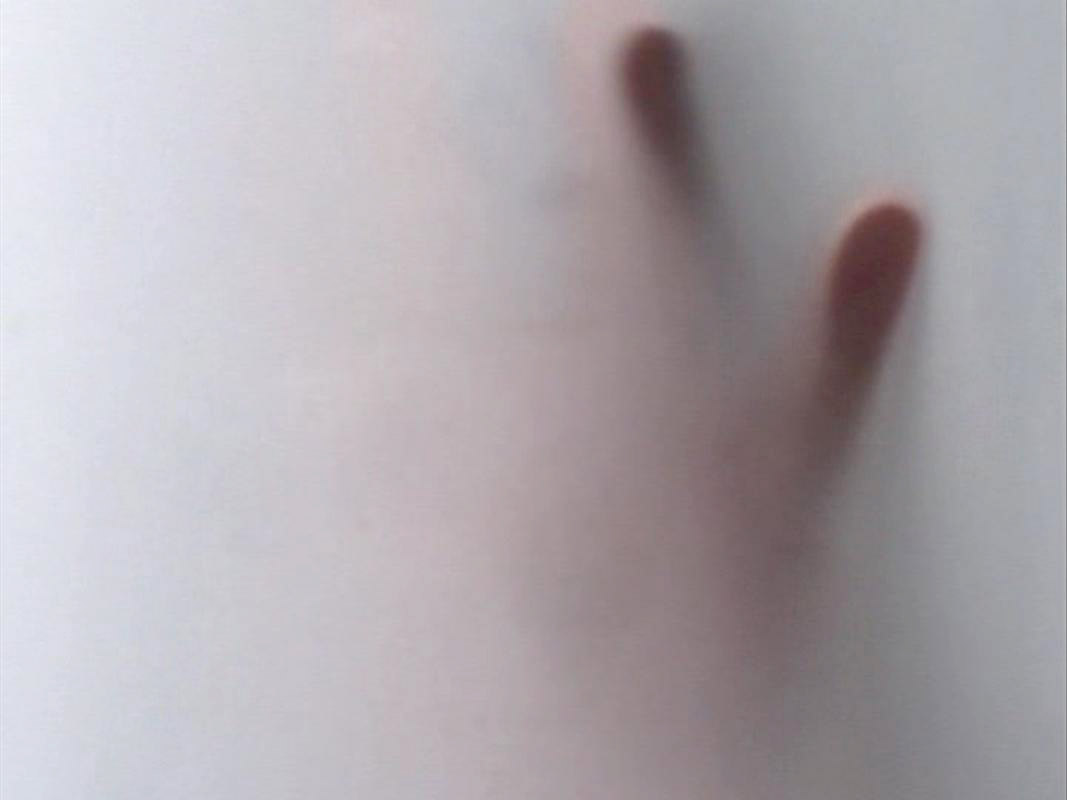

While I have used images from the conflict I also attempted to introduce the image of light, or reconciliation, symbolised by a milky white screen, and an individual trying to penetrate through the light; trying to break through the screen glass and bring light to the audience (figs. 44-48).

Figure 44: Still image from the film Whispers in the Dark (2006). Image © Gil Dekel.

Figure 45: Still image from the film Whispers in the Dark (2006). Image © Gil Dekel.

Figure 46: Still image from the film Whispers in the Dark (2006). Image © Gil Dekel.

Figure 47: Still image from the film Whispers in the Dark (2006). Image © Gil Dekel.

Figure 48: Still image from the film Whispers in the Dark (2006). Image © Gil Dekel.

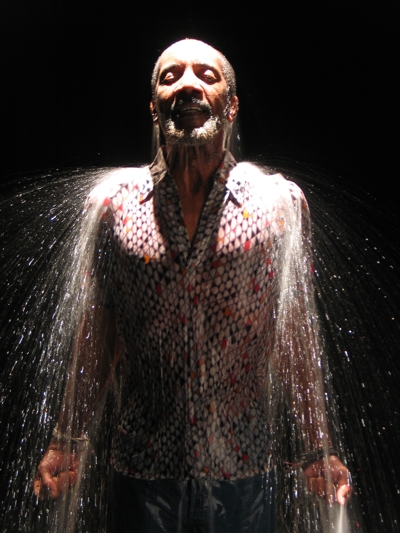

Video artist Bill Viola has created the work Ocean Without a Shore (2007) where individuals are slowly approaching out of darkness and moving towards the light (fig. 49-50). Light, Viola (n.d.) asserts, serves as a threshold one needs to pass in order to be materialised into this life.

Figure 49: Bill Viola, Ocean Without a Shore, 2007, High Definition video triptych, two 65” plasma screens, one 103” screen mounted vertically, six loudspeakers (three pairs stereo sound). Room dimensions variable, Production still (performer Blake Viola). Photo: Kira Perov. Image obtained from Bill Viola Studio. Permission to use image obtained from Bill Viola Studio.

Figure 50: Bill Viola, Ocean Without a Shore, 2007, High Definition video triptych, two 65” plasma screens, one 103” screen mounted vertically, six loudspeakers (three pairs stereo sound). Room dimensions variable, Production still (performer Darrow Igus). Photo: Kira Perov. Image obtained from Bill Viola Studio. Permission to use image obtained from Bill Viola Studio.

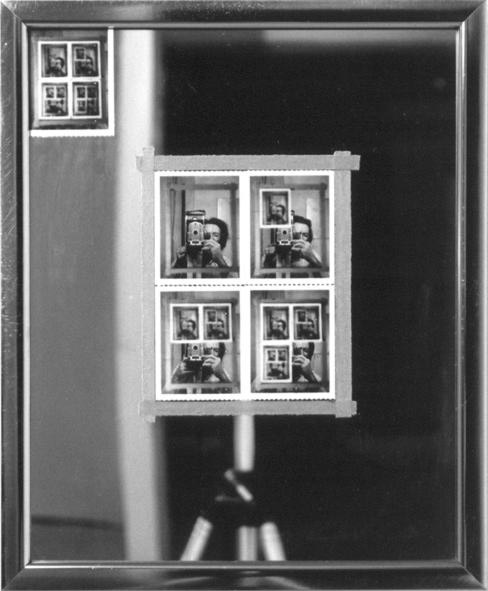

In both my work and in Viola’s, light is seen as a material, an image with sustainability. This is a good example for the way in which artists approach images. Artists seem to relate to image as an object to itself. Image seems to hold a denotative aspect, describing the thing, as well as a connotative aspect, describing something additional. Artist Michael Snow’s work Authorization (1969; fig. 51) seems to epitomises this idea with an image within an image.

Figure 51: Michael Snow, Authorization (1969, black and white polaroid photographs, adhesive cloth tape, metal frame, mirror, 54.5 x 44.5 cm.) Collection of the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, Canada. Image © the artist. Permission to reproduce and upload the image online obtained from the artist.

By choosing the title Authorization, and showing himself as part of the image while taking the image, it seems that Snow emphasizes the notion that image, as seen through the eyes of the artist, is under the authority of the artist, as if created by the artist himself.

Words and images are tools through which artists make an initial registration to give meanings to their emotions. With the act of identification, the emotiovisual faculty provides artists an experience of both feeling and seeing the world through new eyes, as well as observing it and making sense of it through reflection.

Table of Content:

- 1. Thesis Title Page

- 2. Dedication

- 3. Table of Content

- 4. Lists (icons, diagrams, graphs, figures)

- 5. Abstract

- 6. Introduction —

- 7. Literature Review (pt 1 of 2)

- 7. Literature Review (pt 2 of 2)

- 7.1 Summary of Literature and Intentions of the Investigation

- 8. Methodology

- 8.1 Methods

- 8.1.1 Phenomenology

- 8.1.2 Grounded theory

- 8.1.3 In-depth interviews

- 8.1.4 Art practice as a research method

- 8.1.5 Self exploration

- 8.1.6 Data collection and analysis

- 8.1.7 Humour

- 9. A Body of Practical Actions

- 9.1 Artistic choices

- 9.1.1 Actions1 – individual

- 9.1.2 Actions2 – individual in a group

- 9.1.3 Actions3 – collective individuals

- 9.2 Core themes (pt 1 of 2)

- 9.2 Core themes (pt 2 of 2)

- 10. Stimulation

- 10.1 Sensing —

- 10.2 Feeling —

- 10.3 Acknowledging —

- 10.4 Summary of chapter 10

- 11. Internalisation

- 11.1 Shape —

- 11.2 Movement

- 11.3 Summary of chapter 11

- 12. Application —

- 12.1 Place ——

- 12.2 Space ——

- 12.3 Summary of chapter 12

- 13. Conclusion of body chapters 10-12

- 14. Testing the conclusion in practice – a participatory art workshop experiment

- 14.1 Practical preparations

- 14.2 The structure of the guidance

- 14.3 The workshop experiment

- 14.4 Conclusions of the experiment

- 15. Thesis conclusions

- 16. Suggestions for further research

- 17. Appendices (pt 1 of 4)

- 17. Appendices (pt 2 of 4) – Action table/list

- 17. Appendices (pt 3 of 4) – Content analysis of interviews

- 17. Appendices (pt 4 of 4) – Feedback on films

- 18. References